What's Your KCQ?

Once a star of the Kansas City skyline, this 90-foot cow statue now sits alone in park

Readers who have walked the Riverfront Heritage Trail sometimes write in to ask about some of Kansas City’s more obscure public art pieces, such as West Pennway’s miniature Mayan pyramid or the I-670 pedestrian bridge’s iron birds. One piece, however, stands above the rest as an object of reader intrigue: the Hereford Bull atop a pillar in Mulkey Square Park.

Factory workers in this part of Kansas City once dressed the nation. What happened?

At its height, Kansas City’s garment industry dominated much of the U.S. clothing market and was the second largest employer in town behind the Stockyards in the West Bottoms. Over the span of 50 years, it grew from a small wholesale district into one of the most robust manufacturing sectors in the Midwest.

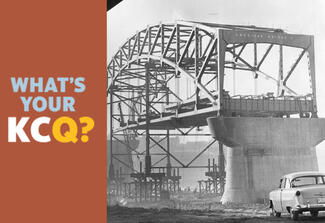

From labor strikes to demolition, here’s the history of Kansas City’s Buck O’Neil Bridge

How a 'border ruffian' who supported slavery got a monument honoring him in a KC park

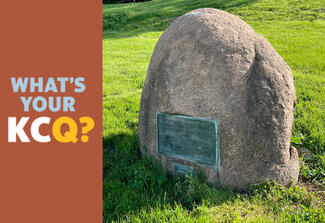

On a recent visit to Penn Valley Park, a reader noticed an oddly placed stone along Penn Drive south of the lake. A plaque embedded into its surface reads: “To the author of Annals of the Great Western Plains, Charles Carroll Spalding, who in the day of small things had the bold vision to foresee the future city.”

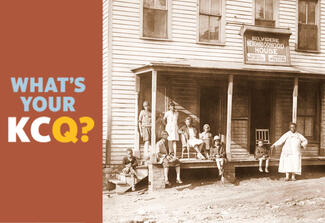

Belvidere Hollow: KCQ unearths Kansas City’s Lost Black neighborhood

In the Historic Northeast, east of downtown and just beyond Interstate 29, lies Belvidere Park — what now may appear to be an empty space. But at the turn of the 20th century, the area was a burgeoning Black neighborhood.

A local reader reached out to What’s Your KCQ? — a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star — to see if Belvidere Hollow still exists. The short answer is no, but that comes with a story.

A pool? A skate park? The real story behind this KC neighborhood’s unique sculptures

A reader was intrigued by a handful of concrete structures resembling skateboard ramps on a grassy area off The Paseo, near 58th Street and Lydia Avenue — and reached out to What's Your KCQ?, a collaboration between The Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, for an explanation.

From a distance, these curved concrete surfaces bear a resemblance to ramps at a skatepark. But a closer look reveals gentle slopes interspersed with grassy patches, which would make skateboarding impractical.