Factory workers in this part of Kansas City once dressed the nation. What happened?

At its height, Kansas City’s garment industry dominated much of the U.S. clothing market and was the second largest employer in town behind the Stockyards in the West Bottoms. Over the span of 50 years, it grew from a small wholesale district into one of the most robust manufacturing sectors in the Midwest.

A reader reached out to KCQ to learn about the history of the garment industry and the district in downtown Kansas City. Where was it? How did it come about? And, in the end, what happened to it?

Before the Garment District

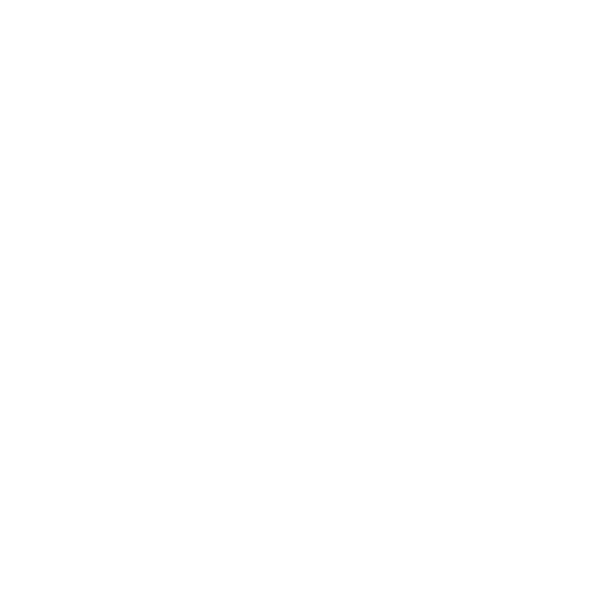

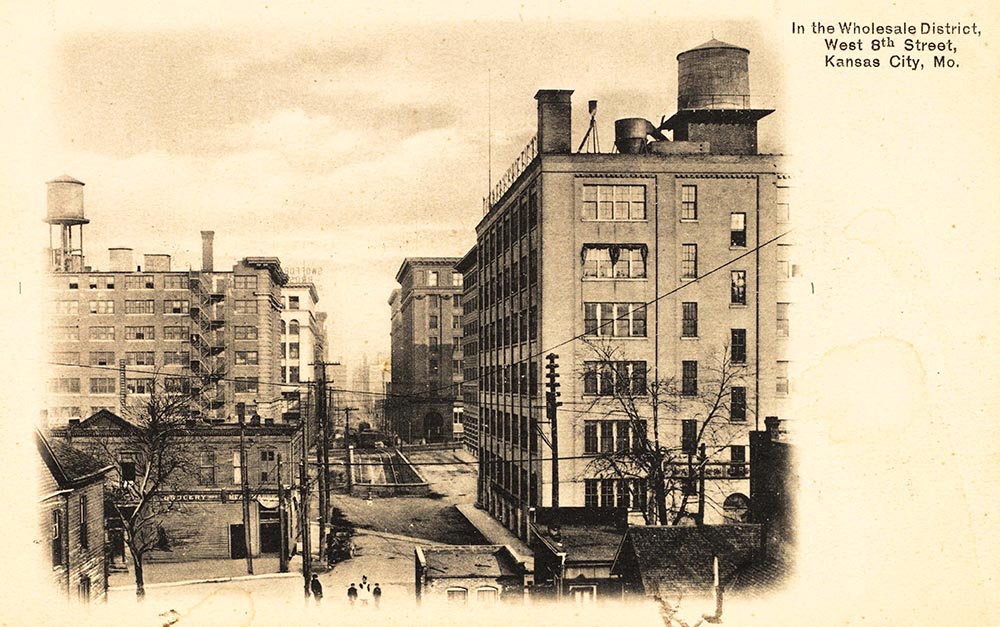

Colonel Kersey Coates, an early frontier Kansas Citian, first owned the land that was initially a residential area in the Town of Kansas in the 1850s. The section, defined by Sixth and 11th streets and Washington and Wyandotte streets, later became the Garment District.

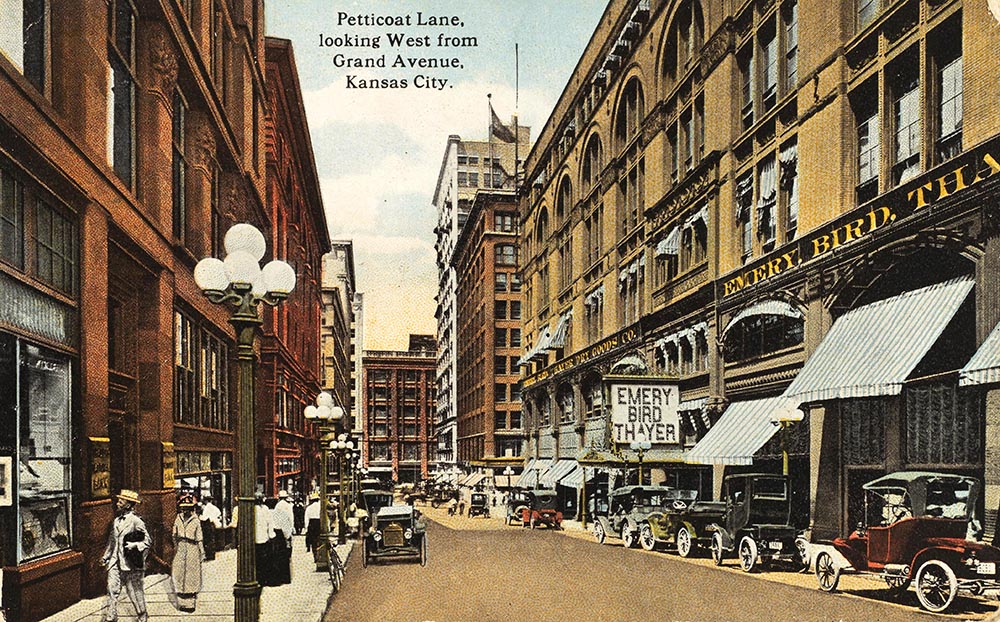

The strip along Broadway transitioned from a residential neighborhood into a cultural hub in the 1870s with the development of the Coates House Hotel and the Coates Opera House.

In the early 1880s, wholesale and retail houses along Main and Delaware streets, as well as in the West Bottoms, gradually moved to that stretch along Broadway.

Kansas City, located at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers, was an attractive location for industries. Around the turn of the 20th century, the building of railroads, and later cable cars and streetcars, accelerated Kansas City’s growth into a major urban, financial, commercial, and cultural hub. With the opening of Union Station in 1914, Kansas City wholesale houses and garment manufacturers distributed materials to nearby regions, which increased the city’s economic growth.

All of these contributing factors of urban development and infrastructure, along with interconnected rail routes, made Kansas City — and its Garment District — the nation's geographic and enterprise center.

Early Years of the Garment Industry

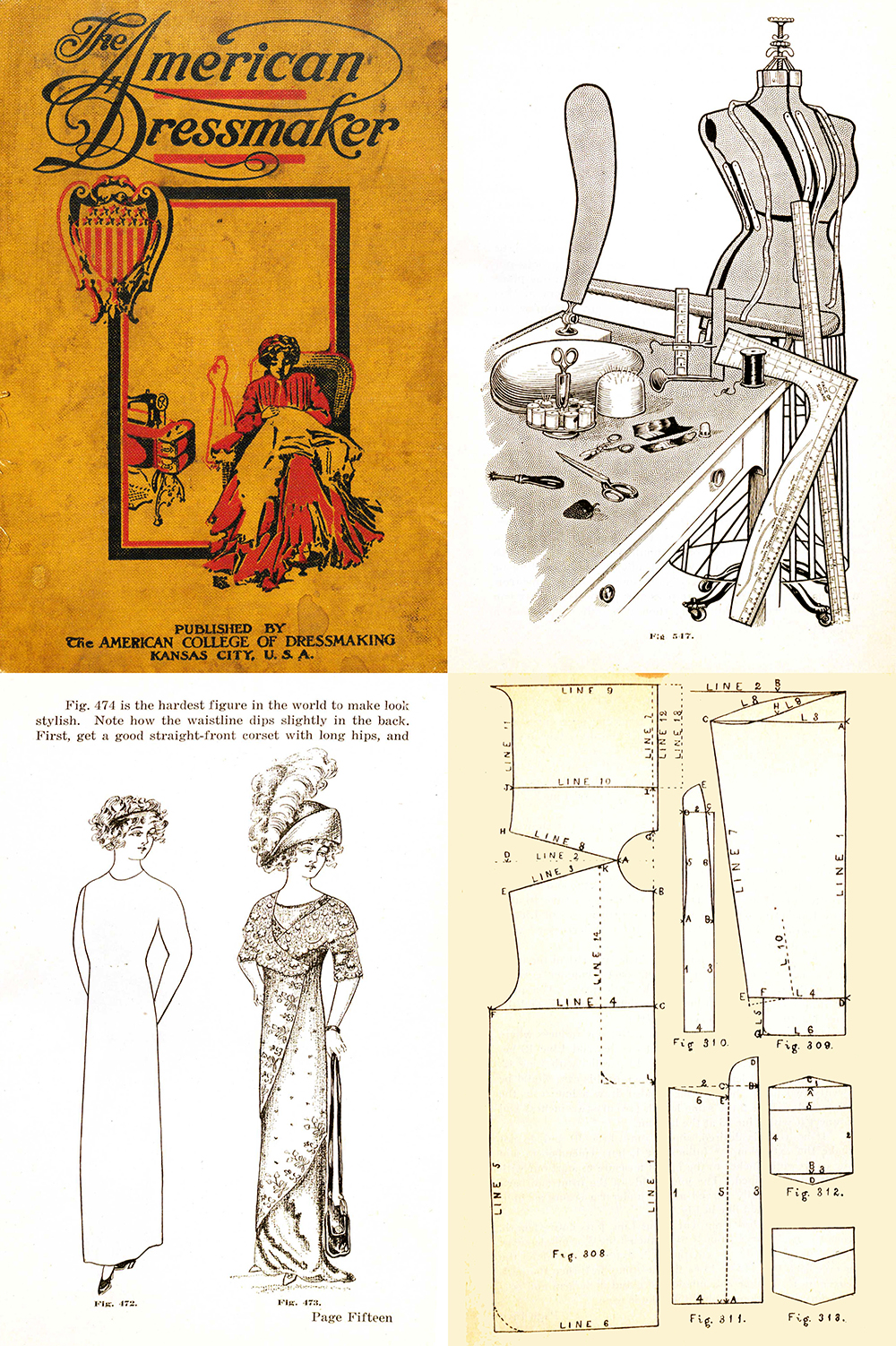

Many early garment company owners and proprietors were immigrants or first-generation Americans. Soon, local Kansas Citians, native Midwesterners, or those looking to establish roots in the metro operated most garment companies rather than outsourcing to larger cities outside of the Midwest.

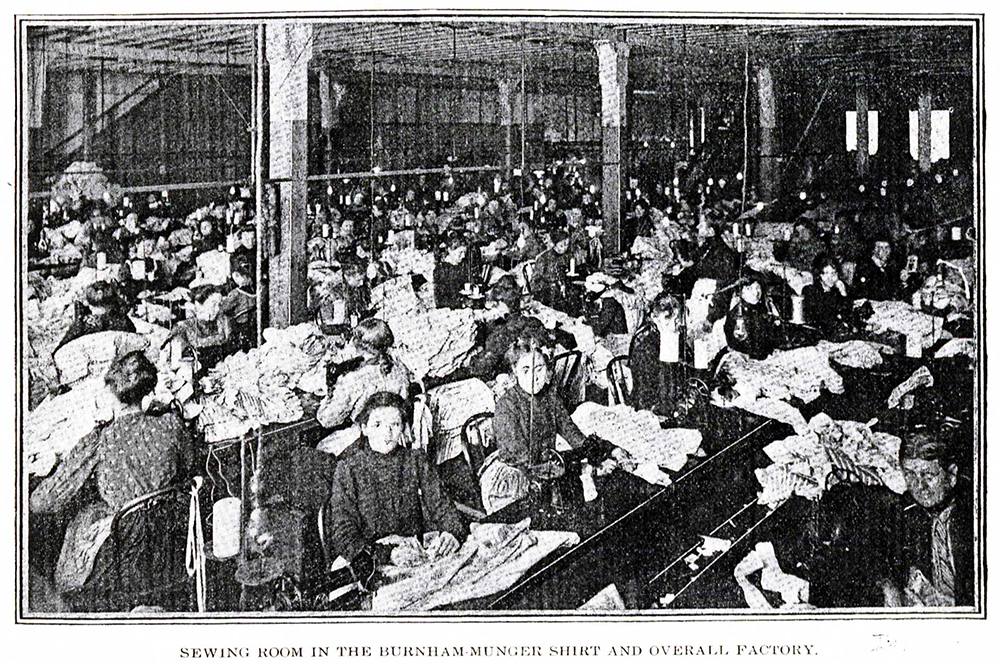

The industry changed incrementally. By 1900, the 11 garment factories in Kansas City producing men’s and women’s clothing were together valued at $1.2 million. In the years immediately following World War I, many clothing manufacturers expanded their operations by taking over wholesale buildings in the district and converting them into sewing spaces and factories. Then, in the 1920s, the number of garment manufacturers increased to more than 40.

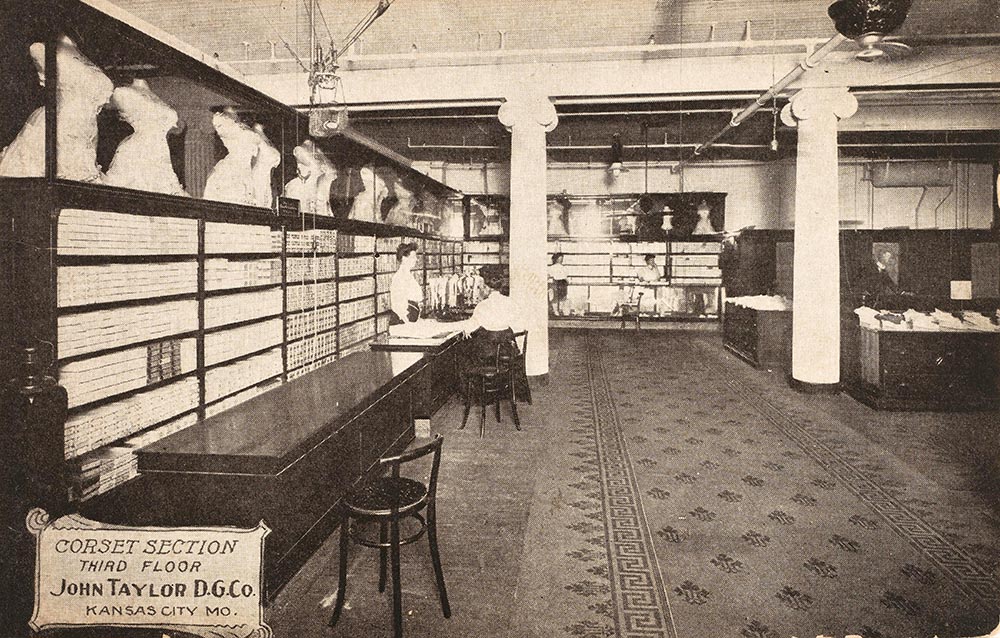

Most garment industry employees were women working as machine operators, models, designers, and office workers. Men usually held positions such as executives, salesmen, spreaders, cutters, pressers, and sometimes designers.

Even during the Great Depression, the Kansas City garment industry continued to grow. Companies began specializing in clothing pieces for average Americans, targeting smaller markets in nearby rural towns rather than relying on larger department stores or mail-order houses.

Unionizing

Garment unions existed as early as 1898 in Kansas City, but workers did not overwhelmingly join them until the 1930s. These unions, like the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), improved working conditions for garment employees. For instance, unions banned the practice of “homework,” meaning workers had been expected to complete unfinished tasks at home outside of regular working hours, if they were unable to meet industry deadlines.

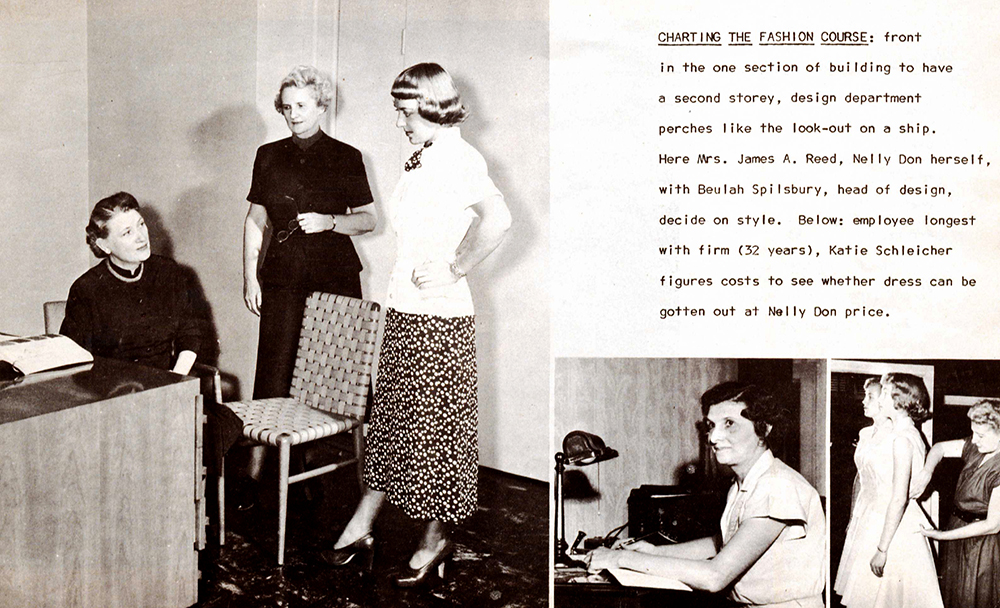

Some businesses, like the Donnelly Garment Company founded by Nell Donnelly Reed, resisted allowing their workers to join the local chapter of the ILGWU, which had formed in 1933. Court battles ensued between the ILGWU and the Donnelly Garment Company from 1937 to 1948, but ultimately, Reed’s company had to decertify their internal company union.

Donnelly employees waited to join the ILGWU until Reed retired in 1956.

World War II

When the U.S. entered the war in late 1941, most industries shifted to aiding and supporting the war effort. Kansas City’s garment industry produced millions of uniforms and specialized clothing for the Army and Navy. Despite challenges in meeting government specifications, as well as labor shortages, the garment industry maintained and even improved quality standards.

By 1945, Kansas City had more than 80 garment factories estimated to be worth a total of $75-100 million. They not only increased civilian clothing production after the war but employed 6,000-7,000 people.

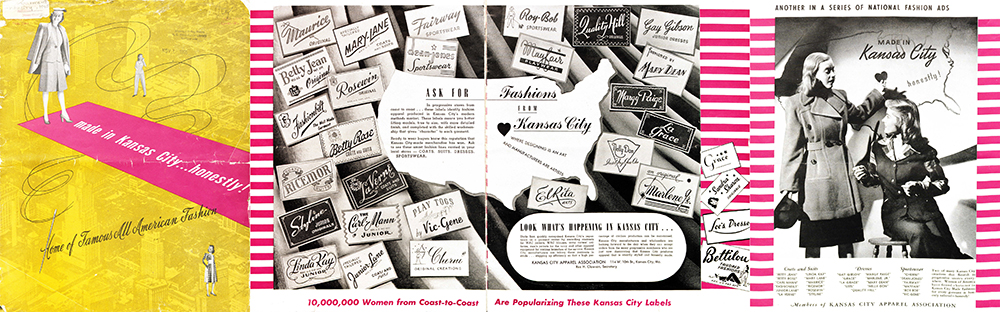

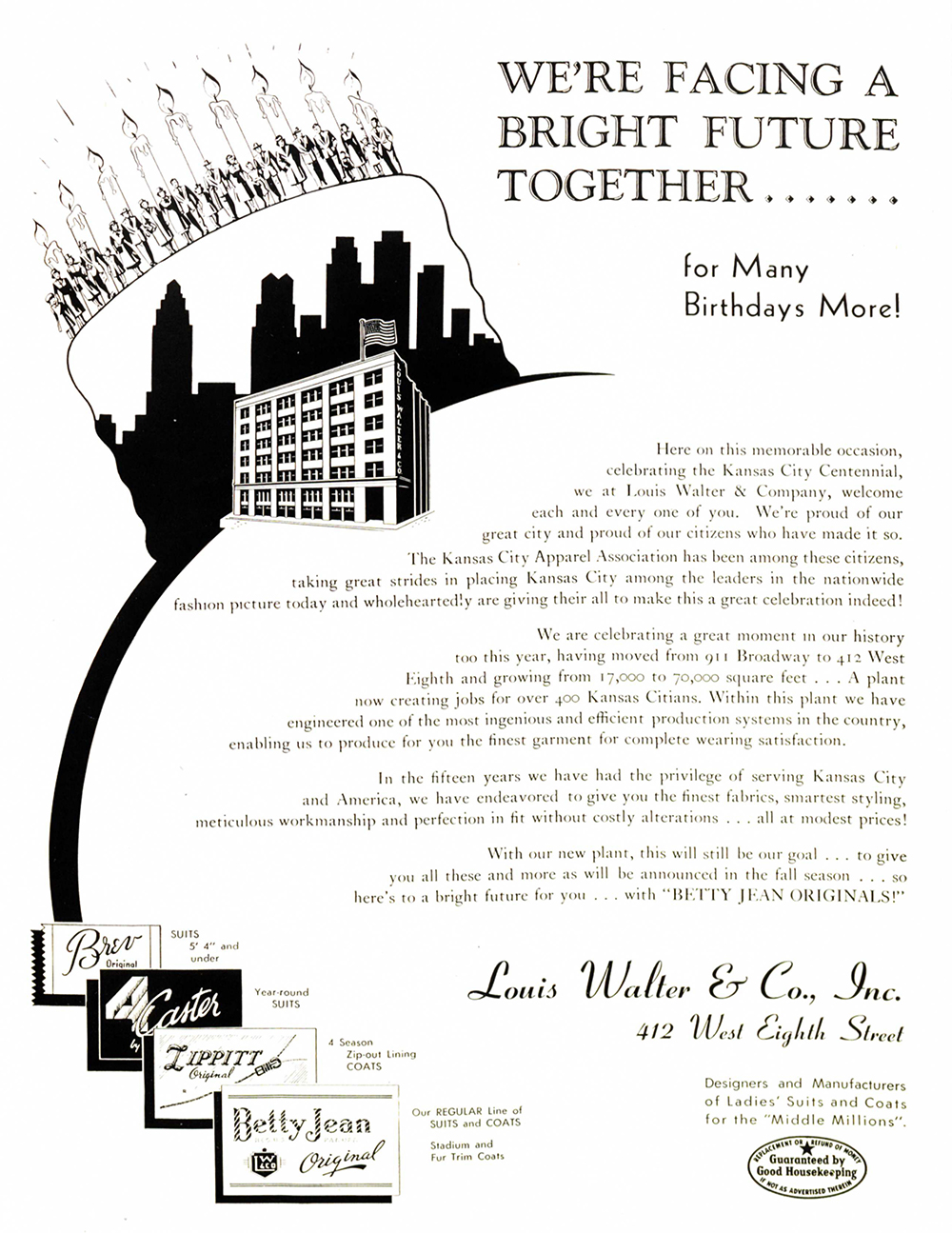

In 1945, the Kansas City Apparel Association, a trade group which consisted of local garment industry companies, ran a national advertisement campaign called “Made In Kansas City … Honestly!” In this booklet, the association promoted Garment District businesses and emphasized the industry's priority of producing high-quality items.

Methods

Unlike its more traditional counterpart in New York, the Kansas City garment industry largely employed unskilled workers who seldom made garments from start to finish. Garment employers primarily hired these laborers because few in the region had prior training, and it was cheaper to train internally on one specific aspect of the garment-making process.

Nell Donnelly Reed is credited with introducing the assembly line method for making clothing that most of the local garment industry adopted and called the “section system.”

With this cost-effective section method, workers sewed pockets, ironed sleeves, or bundled pieces in an assembly line for eight hours a day – but no one completed an entire piece of clothing. This efficiency allowed the local garment industry to perfect “ready-mades” for consumers across the country.

The industry also practiced efficiency through “working the seasons,” meaning making summer clothes in the winter and fall and winter clothes in the spring and summer.

Local garment manufacturers used a variety of materials, including wool, cotton, silk, rayon, fur, leather, satin, and velvet. The main types of Kansas City-made garments were men’s work clothes and underwear; women’s dresses, coats, and suits; girls’ dresses and coats; sportswear, including athletic uniforms; hats; robes; and more. With this variety, it was believed that one in seven American women owned a Kansas City-made garment.

Aftermath

From the 1950s to the 1980s, the local garment industry declined and eventually disappeared. Casual fashion trends in the 1960s and 1970s reduced demand for traditional and formal garments.

Manufacturing moved to cheaper international labor markets that undermined American unions. The rural population, Kansas City’s primary market, decreased while also shifting to discount retailers and box stores that undersold small businesses and department stores. These factors and more led to the demise of the Kansas City garment industry.

While the former garment and wholesale district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, developers have converted the factory buildings into apartments, offices, and restaurants.

Opening of the Historic Garment District Museum and Dedication of Garment District Monument, October 4, 2002.

Hoping to keep the industry and district’s history alive, seasoned garment industry insiders Ann Brownfield and Harvey Fried co-founded the Historic Garment District Museum in 2002. The collection is now housed at the Kansas City Museum.

Today, a 22-foot-tall button and needle sculpture at Eighth Street and Broadway honors the legacy of the district and those who operated it.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.