KCQ Investigates Petticoat Lane

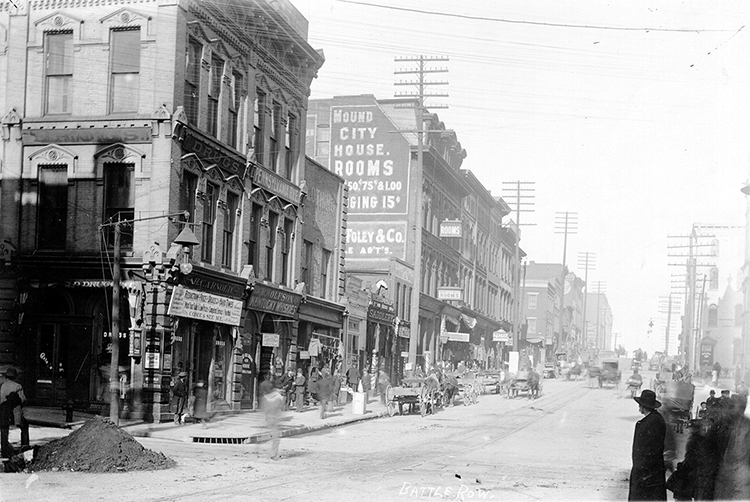

Standing at 11th and Main streets downtown is a peculiar street sign labeled Petticoat Lane. Taking in the surrounding parking garages, banks, and office buildings, it can be difficult to discern why this short byway was named after women’s undergarments of a bygone age.

Reader Scott Allen asked us to get to the bottom of it.

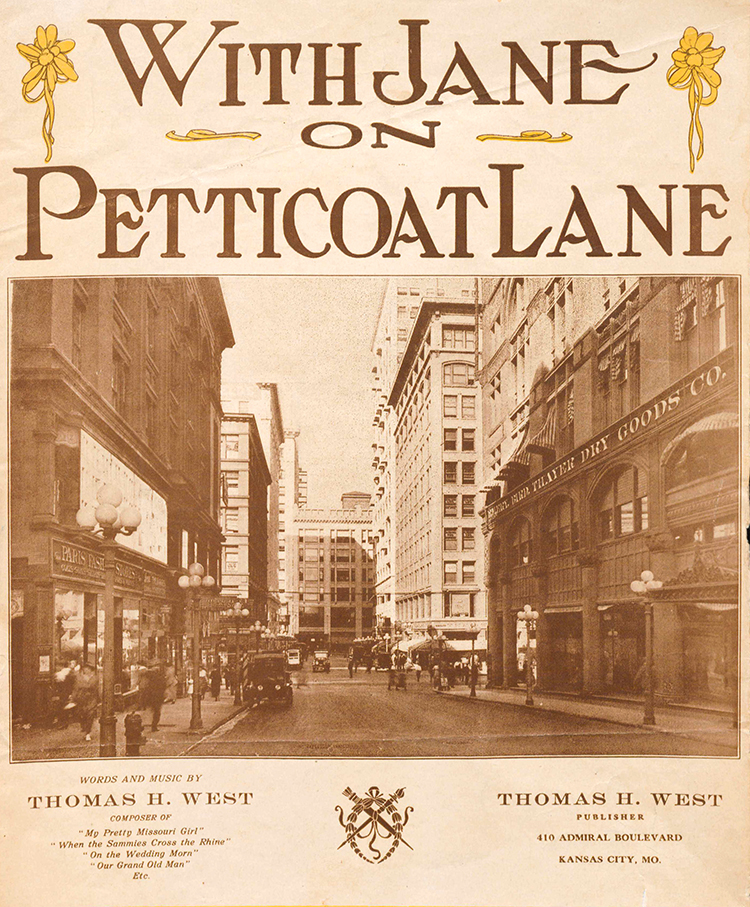

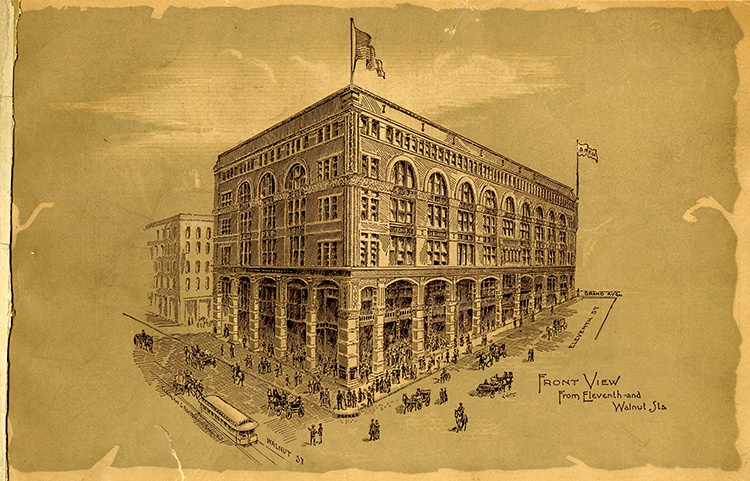

To begin, we must imagine an 11th Street of a different age – inhabited by department and dry goods stores, bustling with buggies and streetcars, and crowded with shoppers. Over the years, local outlets like Emery, Bird & Thayer; John Taylor’s; Harzfeld’s; and Peck’s gave way to national chains like Macy’s and Dillard’s. And they all made the little downtown street an ideal place to buy a petticoat.

By the 1950s, 11th Street between Main and Grand was widely recognized as Kansas City’s premier shopping destination – and shoppers and merchants alike would have known it as Petticoat Lane. Department stores had used the nickname for decades, so did civic boosters, and there were songs named after it. The Independent, Kansas City’s society journal, ran a regular gossip column called “Petticoat Levities.”

The name was so widely used that 10th Street merchants tried to get in on the fun, branding their stretch of road east of Main “Tailors’ Row” in 1898.

But it was Petticoat Lane that had staying power. Though not everyone embraced the nickname immediately. In 1899, a petition was circulated to rename the street Hogan’s Alley in honor of John Hogan, a police officer assigned to keep the shopping district free of “mashers,” an old term for catcallers. Hogan became a popular figure in the shopping district over the years, but it was Petticoat Lane that was embraced by merchants and shoppers alike.

In 1952, City Manager L.P. Cookingham authorized the installation of decorative Petticoat Lane signs below the existing 11th Street signs. While his gesture was appreciated, downtown merchants wanted the change made official and, in 1966, the city council moved to formally rename the stretch of street – seemingly an easy day in the council chambers.

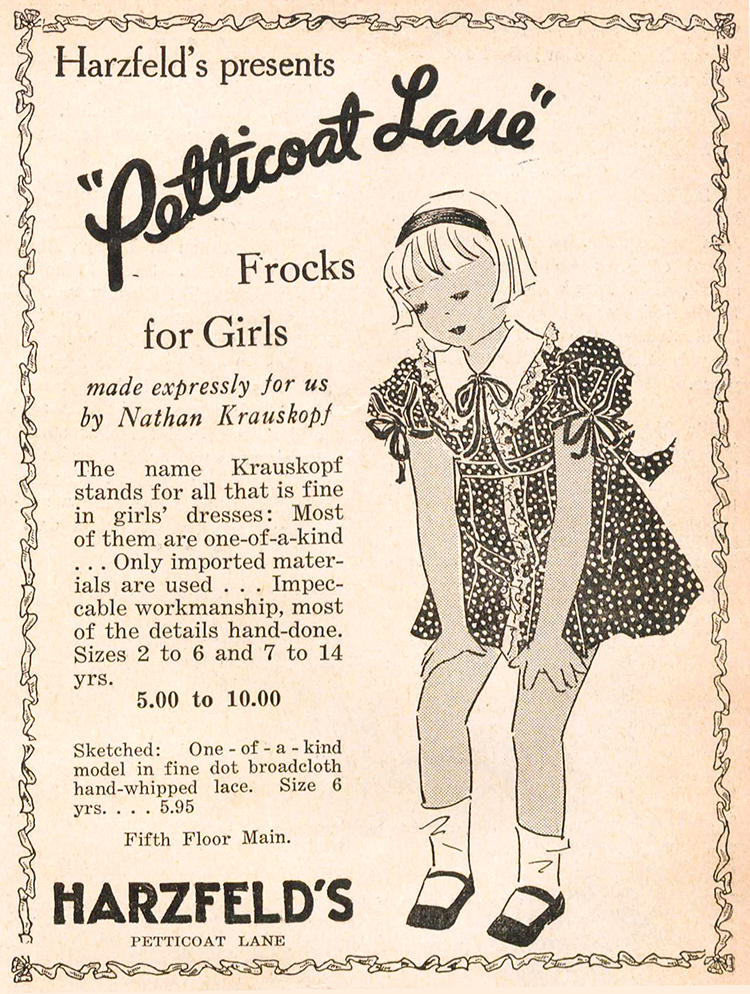

But Harzfeld’s, one of the first department stores to settle in the area and begin its transformation into a shopping district, objected to the change. Its operators argued that their nationally marketed Petticoat Lane line of clothing was not only trademarked, but that the name had been coined by the store’s founder, Siegmund Harzfeld. The claim set off a public debate about the nickname’s origins.

Some found the simplest explanation more believable: 11th Street was the home to many department stores where one could find a good petticoat. Others insisted the name was borrowed from Petticoat Lane Market in London, adding an air of sophistication and glamour to downtown shops. Others still claimed the name was from gusty downtown winds that would rush up the narrow street and frequently upturn women’s skirts to reveal hidden petticoats. Officer Hogan would not have approved.

City archivist and historian George Fuller Green was called in to clarify the matter and verified that the name was widely used by 11th Street merchants by the 1890s. Days later, The Kansas Times weighed in. The name, it wrote, was from “In Petticoat Lane,” an 1896 poem written by Minnie McIntyre. The newspaper noted that the poem was written to celebrate the transformation of 11th Street from a location dotted with saloons and filled with drunkards to a genteel place of civility, owing to the opening of the department stores.

Sometime later, Kansas City resident Ada M. Kassimer attempted to put the issue to rest. Writing to The Kansas City Star, she described growing up a childhood friend of Minnie McIntyre and her sister Pearl and personally recalled Minnie referring to 11th Street as Petticoat Lane “not later than 1892,” well before her poem appeared in The Times.

So, who was McIntyre, and did she really write the poem to celebrate 11th Street saloonkeepers getting the boot?

She was born in 1873 and started her life in St. Louis. At an early age, her father, employed by the Missouri Pacific Railroad, was killed in an accident. Her mother, along with younger sister Pearl, resettled in Kansas City.

Attending the Humboldt School and later graduating from Central High, McIntyre developed a keen interest in the written word. A leader of the Western Authors’ and Artists’ Club, she frequently gave readings of classic literature. But it was her poetry that first earned her acclaim. She was described in the April 17, 1892, issue of The Times as a “young Kansas City poetess” who had already written numerous poems published in the newspaper, some while still attending high school.

While it is true that McIntyre’s “In Petticoat Lane” was published in 1896, it should be noted that her “The Reflective Woman,” a prose poem published in The Star in 1895 used the name to describe KC’s shopping district. Her poems, frequently romantic and often humorous, touched on the lighter sides of life.

Interestingly, a poem by “S.W. Simmons” appearing in The Star in 1897 was also called “In Petticoat Lane.” Was it McIntyre, using a pseudonym? It’s difficult to say. She often wrote anonymously or using pen names, but the piece bears the characteristics of her work. It tells of a man named O’Grady who meets a “Miss Minnie McShane” while strolling down Petticoat Lane. The two fall in love, marry, and all is well until his new wife’s shopping habit exhausts his bank account, forcing O’Grady to wish he’d never set foot on Petticoat Lane or met Miss Minnie McShane.

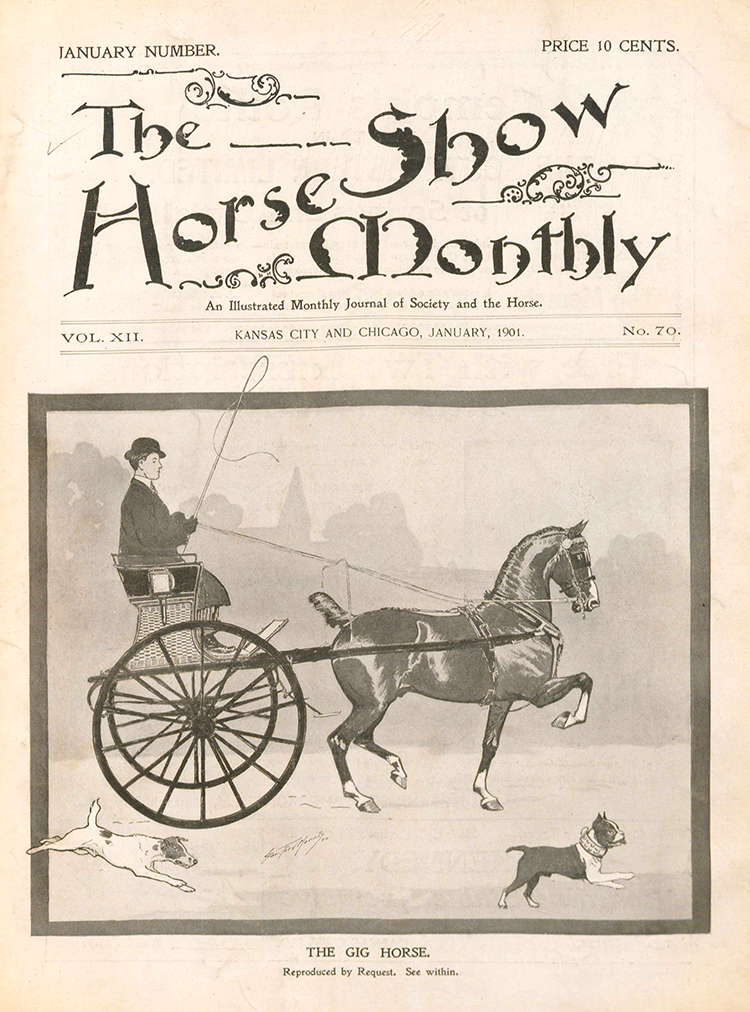

Beyond her literary skills, McIntyre had in interest in horses and became a nationally recognized show judge. In consideration of her unique set of skills, she was hired as an associate editor for The Horse Show Monthly. Often writing under the name “Virginia,” she hired her sister Pearl to write a regular column under the pen name “Miss Rose Budd.”

It was at this point in the young author’s life that Kansas City’s saloon issue boiled over.

In 1894, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and Women’s Suffrage Association picked a fight with downtown saloonkeepers. Arguing before the Board of Police Commissioners and the mayor, their calls for crackdowns on drinking establishments raised two issues. First, they claimed that several saloons regularly opened on Sundays, then a violation of city ordinance. And they called them a corrupting influence on young women, insisting that many saloonkeepers were operating private “wine rooms” upstairs or in the back of their buildings where the ladies – prohibited by law from patronizing saloons – could gather, drink, and entertain guests.

Many well-to-do Kansas Citians of the 1890s were ready to leave the city’s frontier past in the history books. As city limits pushed south away from the river, they welcomed a wave of gentile refinement, especially so in the burgeoning downtown shopping district on 11th Street. The saloonkeepers resisted, but some of the most egregious offenders saw their business licenses revoked.

The reformers pressed further, taking their fight to the 1896 mayoral election. They championed Republican lawyer and police judge James M. Jones, described by The Star as the “most moral of candidates,” who promised to throw the book at vice in Kansas City. The race was close, but Jones emerged victorious.

Under his administration, saloons were hit with new restrictive ordinances. The mayor was empowered to close them at his discretion, Sunday beer deliveries were outlawed to remove the temptation for saloonkeepers to open their doors, and annual license fees were increased from $250 to $750.

Jones also went after gambling establishments, and while he had some legislative success on this front, he made an enemy of a rising Democratic political star with deep interests in saloons and gambling – Alderman Jim Pendergast. By 1900, it was the Pendergast machine-selected candidate, James A. Reed, who took the mayoral race.

Was it the clampdown on saloons that inspired McIntyre’s Petticoat Lane poems? That’s also uncertain.

While many of her works dealt with enlightened and well-mannered topics, she did not shy away from the grittier side of life. In a poem published in the program for the Kansas-Missouri football game played on Thanksgiving Day in 1896, she included the line, “It’s the battle of the strongest and the weak must kiss the wall.”

It is also doubtful that she shared the hardline stance against saloons adopted by organizations like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Issues of The Horse Show Monthly are crammed with advertisements for distillers and beer brewers. If she did have anti-saloon leanings, she kept them in check for the benefit of her writing career.

In a letter to The Star in 1953, McIntyre recalled writing the Petticoat Lane poems. “I do not know what inspired the lines,” she said, “but at the time I lived only a block from Eleventh Street. She described shopping trips to Emery, Bird & Thayer with her mother and marveling at the crowded street.

Rather than the varied explanations offered up over the years, Petticoat Lane belongs to McIntyre. It’s conceivable that she simply thought it would be charming for the downtown shopping district to have a fun, posh-sounding nickname that associated it with cosmopolitan London and put the idea down on paper. Thanks to her clever way with words, the name stuck.

In 1905, McIntyre was made full editor of Chicago-based Bit & Spur, another horse magazine. She remained there until marrying in 1908. The union was short-lived and around 1916 the widowed Minnie McIntyre Wallace joined her sister in Beloit, Wisconsin. There, she was hired as the society editor and columnist for The Beloit Daily News. She stayed with the paper for over 25 years before passing away in 1959.

Back in Kansas City, the battle over Petticoat Lane waged on. The city council, satisfied that the name did not originate with the Harzfeld’s store, officially renamed 11th Street between Main and Grand as Petticoat Lane. It’s complaint with the city put to rest, Harzfeld’s trained its sights on Macy’s, which had recently taken over the old John Taylor’s building.

A motion in U.S. District Court sought to prevent Macy’s from using Petticoat Lane in its store and promotions and asked for financial damages for trademark violation. The outcome of the case is unknown, but Macy’s and other shops on 11th Street continued to use Petticoat Lane in their print advertising. So, it’s doubtful the matter was settled in Harzfeld’s favor.

Another struggle over Petticoat Lane and the downtown department stores took the form of a civil rights boycott, which started just before Christmas 1958 and lasted seven weeks. Macy’s and other shops were glad to sell to Black shoppers, but some stores’ dining rooms were off limits to them. Finally, the following February, the stores promised to drop the color barrier.

Sadly, the demise of downtown shopping was on the horizon. The first grand department stores had begun opening on the Country Club Plaza in the 1940s. Suburban malls appeared in the ’50s. Unlike the Petticoat Lane shops, these new retail outlets were easier for suburbanites to reach and offered plenty of convenient parking.

Downtown merchants couldn’t compete, seeing sales drop by greater and greater margins each year. Emery, Bird & Thayer closed its doors in 1968. Harzfeld’s held on until 1984. While a few of the old department store buildings have survived, the office buildings and garages now lining 11th Street were put up during the city’s era of urban renewal, forever changing the character of the area.

Over the next couple of decades, many downtown retail redevelopment plans were floated, but none were able to recapture the charm and excitement that inspired a young Kansas City poet to dream up the name Petticoat Lane.

Submit a Question

Have a Kansas City question of your own? If selected, Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.