From labor strikes to demolition, here’s the history of Kansas City’s Buck O’Neil Bridge

If you're in or near downtown Kansas City this Tuesday, you might hear a loud boom as the final section of a KC landmark comes crumbling down.

The blast this week is the final one needed in the Missouri Department of Transportation's demolition of the John Jordan "Buck" O'Neil Memorial Bridge, previously known as the Broadway Bridge. It began Feb. 15 with the first arch, followed by another blast April 2 for the middle arch.

A curious reader asked What's Your KCQ?, a collaboration between The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library, to explain the history of the bridge.

As with a majority of modern Kansas City's infrastructure, the post-World War II automobile boom drove the decision to build a new bridge across the Missouri River at the time, motorists could choose between the Hannibal Bridge and the Armour-Swift-Burlington (ASB) Bridge, both of which served as hybrid railroad and automobile bridges. However, they became increasingly inadequate to manage the growing traffic demands over the years.

It was the Great Flood of 1951 that convinced city planners to expedite their plans. On July 13, four cargo-laden barges broke free from their moorings at Kaw Point and collided with the Hannibal Bridge's piers. Although its structure was undamaged, planners recognized that losing one of the two crossings would be catastrophic for both the area's economy and commute times.

City Manager L.P. Cookingham outlined a plan for a modern automobile bridge designed by HNTB Corporation. A $13 million bond program financed the new span which would be repaid through tolls.

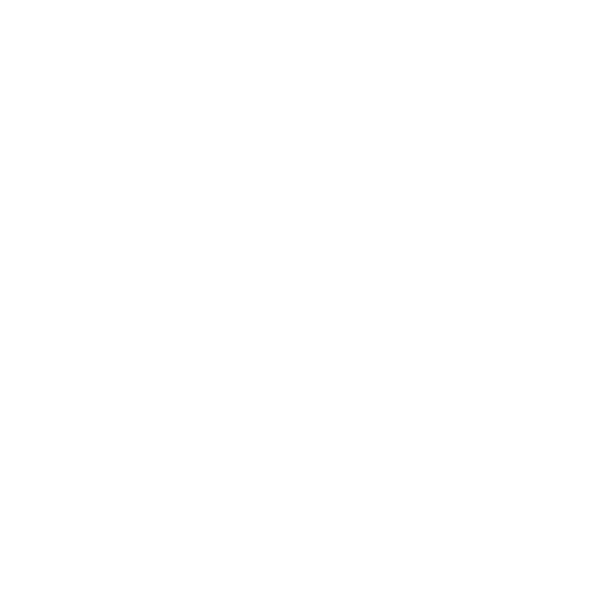

BUILDING THE BRIDGE

Construction began on Nov.11, 1954. Separate crews built the piers across the water and the bridge's footings on the north and south banks. The project required 8,000 tons of structural steel for the trusses. By December, members of the Iron Workers Local 10 were hard at work assembling them.

Trouble arose on Dec. 28, 1955, when members of the Teamsters Local 541 ordered their truck drivers to halt steel deliveries to the job site. The union members were upset that iron workers had been assigned to unload cargo from their trucks, a task the Teamsters considered their responsibility. They were also unhappy because they had no contract with the bridge builders.

While other work continued, there was concern that the two-thirds completed bridge could be washed away if another flood damaged its temporary support structures.

Some relief came on Jan. 13, 1956, when the Teamsters returned to work after their "jurisdictional dispute" with the iron workers was settled by arbitrators. However, the contract issue remained unresolved, leading the Teamsters to picket the worksite again on Feb. 16. This time, it took nine days to resolve the dispute, with steel truss work resuming on Feb. 25.

However, this was not the end of the labor negotiations. On March 1, members of the Hoisting Engineers Local 101, responsible for concrete pouring on the project, went on strike. They held out for 18 days to secure a wage increase.

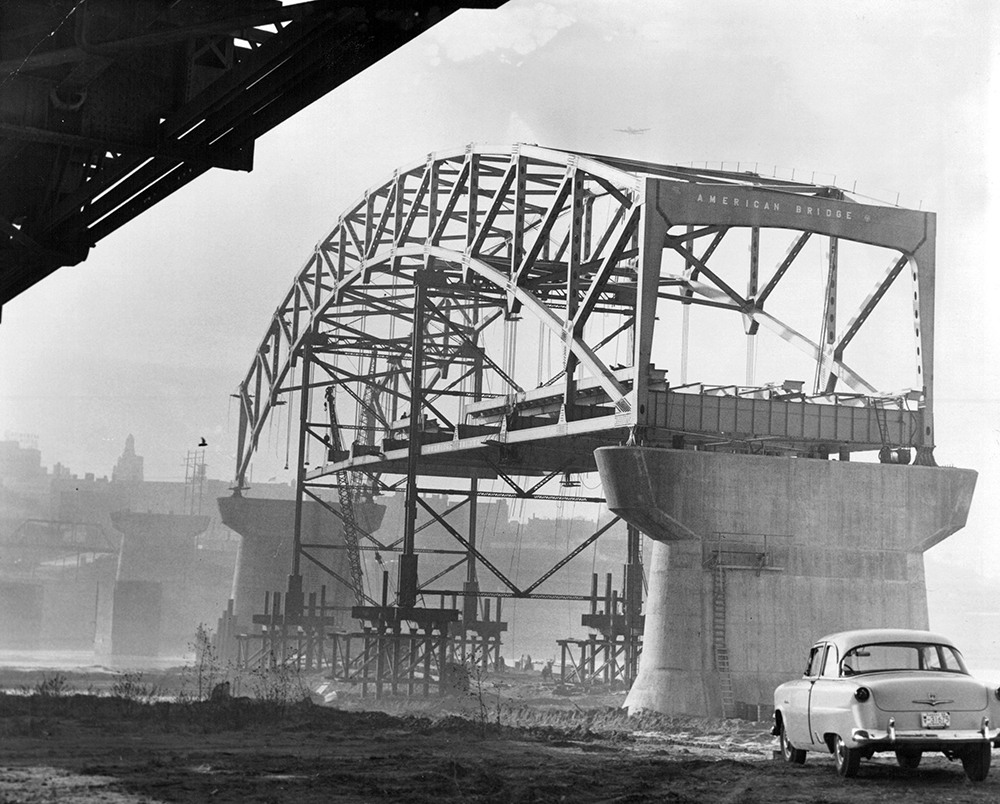

OPENING OF THE BROADWAY BRIDGE

Planners had anticipated a July opening, but the bridge was not ready on time. It officially opened on Sept.5, 1956. That morning, a motorcade carrying local dignitaries traveled from City Hall to the south end of the bridge. Following a concert, speeches by public officials, and blessings from local religious leaders, Paseo High School student Patricia Sue Wilkinson, who had been crowned "Queen of the Broadway Bridge," smashed a glass bottle filled with Missouri River water to formally dedicate the new span.

Mayor H. Roe Bartle officially opened the Broadway Bridge when he snipped a ribbon tied to an old-fashioned toll gate made from cottonwood logs. He used a large pair of ceremonial scissors donated by the Emery, Bird, Thayer department store for the occasion.

The motorcade then proceeded across the river, turned around, and returned over the old Hannibal Bridge, at which point Bartle officially closed it to automobile traffic. In a gesture of goodwill, the city suspended tolls for the remainder of the day to allow the public to traverse the new bridge for free. Louis L. Layton, a city commissioner, was the first to pay the 10-cent toll, crossing one minute after midnight.

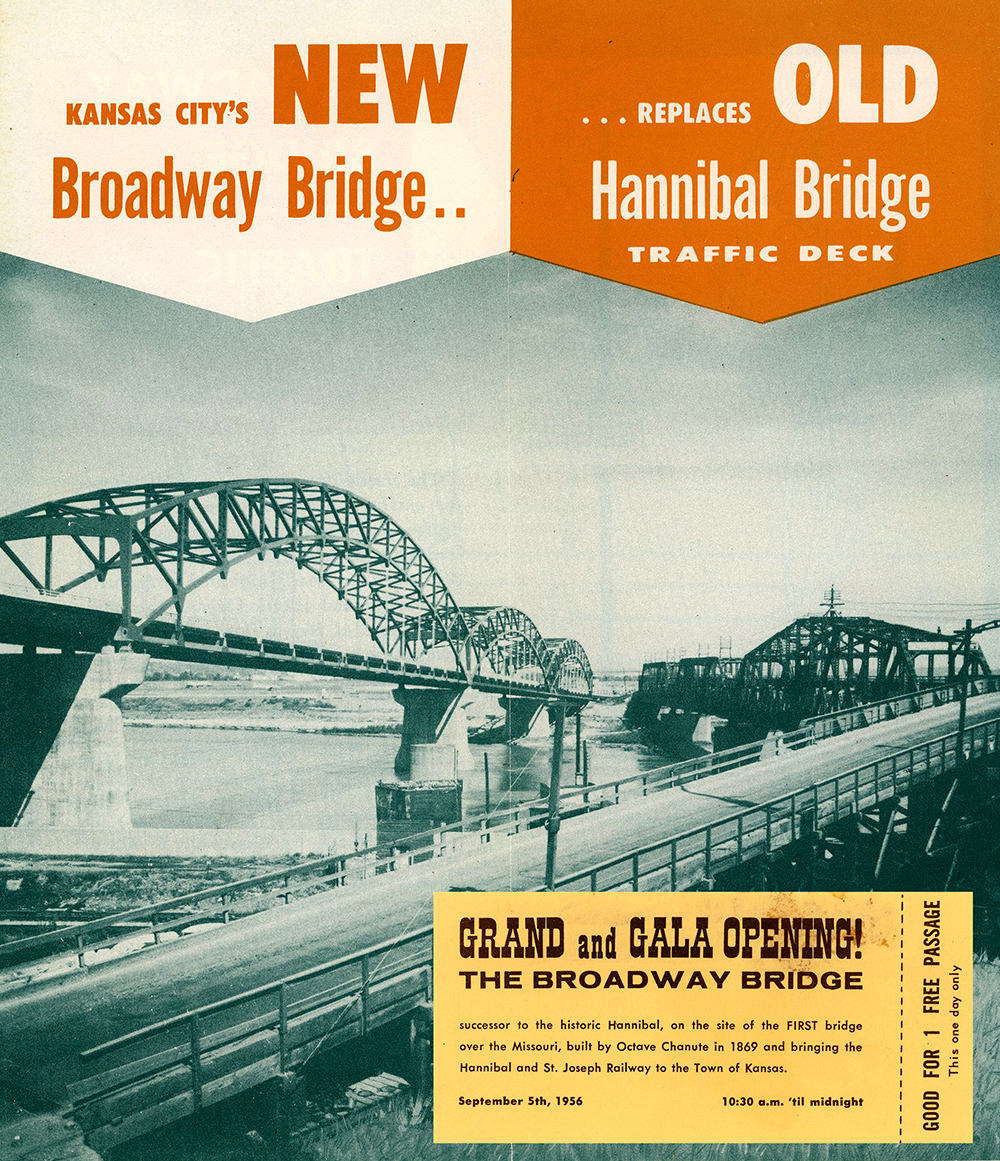

FROM BROADWAY TO BUCK O'NEIL

Tolls generated nearly $40 million over the next three decades before they were discontinued on Jan. 1, 1991. The following year, the city transferred ownership to MoDOT.

Over the years, other changes were made. The completed bridge was originally painted forest green. By the early 2000s, after more than four decades of use, the green paint was coated with rust. As a result, the city decided to repaint it gray.

Once the paint was applied, a lighting system was installed to highlight the bridge's structure at night. Additionally, two illuminated concrete and metal sculptural gateways were added: one at Fifth Street and Broadway to welcome travelers to downtown, and another at U.S. 169 and Missouri 9 to welcome them to the Northland.

A significant change occurred on Oct. 6, 2016, when the bridge was renamed the John Jordan "Buck" O'Neil Memorial Bridge. This renaming honored the sports legend's dedication to championing all things Kansas City and commemorated the 10th anniversary of his passing.

THE BRIDGE'S FUTURE

Even then, the end of the bridge's natural lifespan was quickly approaching. In 2021, MoDOT and the city approved a plan to replace the 1956 structure with two separate modern highway bridges. These new bridges were designed to require less maintenance and upkeep than the old bridge's triple-arch design.

Some city leaders hoped to preserve the old bridge and convert it into a pedestrian-friendly linear park. However, a 2022 feasibility study determined that the project would be cost prohibitive for the city.

Throughout the project, travelers heading north continued to use the old bridge. That changed on Jan. 31, 2024, when traffic was diverted to the new northbound span. MoDOT anticipates all work to be completed by December 2024.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.