Was Lee’s Summit named after Robert E. Lee? What’s Your KCQ? examines the complicated legacy of the town’s namesake

Many assume Lee’s Summit was named for Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and a reader asked What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library, to find out the truth.

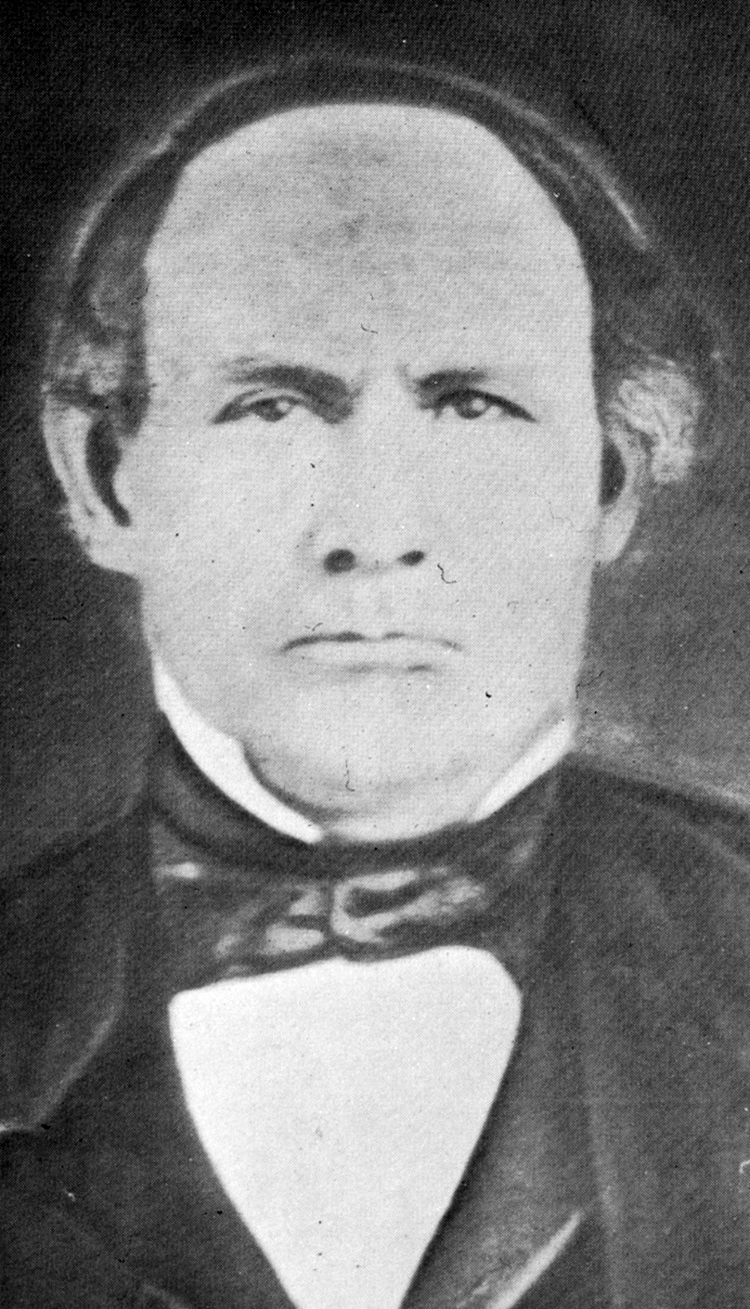

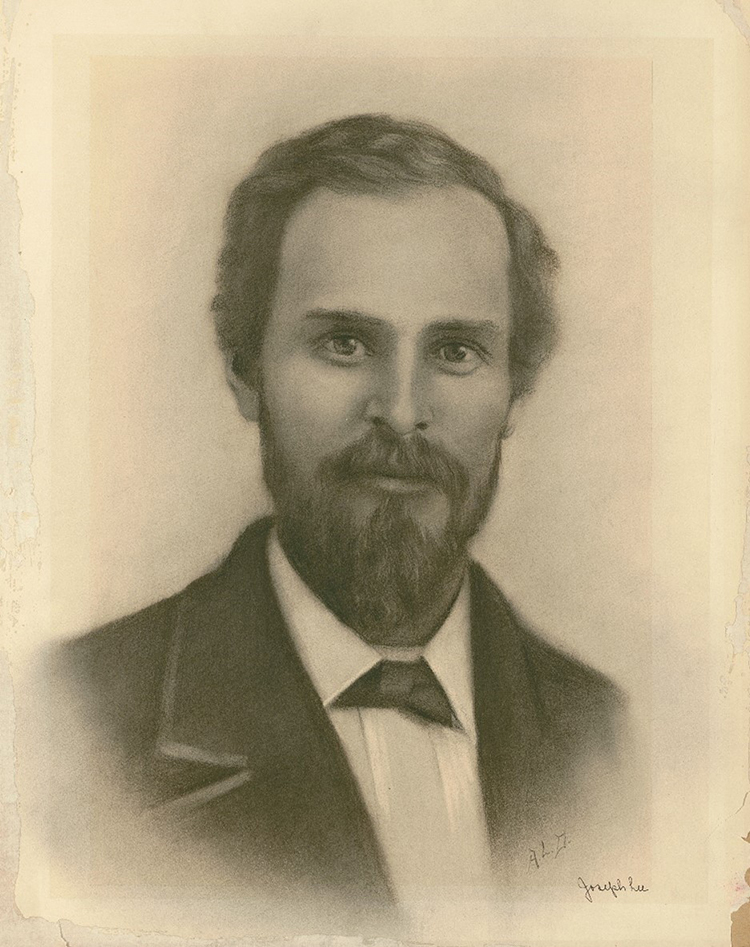

Not only is the Kansas City, Missouri, suburb not named after Robert E. Lee, but the town didn’t take its name from anyone named Lee at all. Rather, it’s named after an early resident, a physician named Dr. Pleasant John Graves Lea.

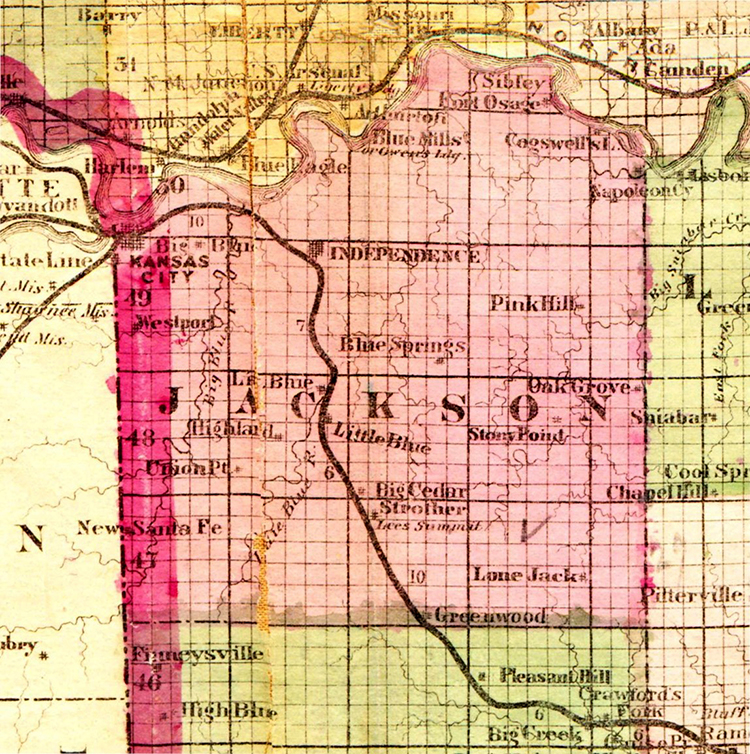

Born in the first decade of the 19th century in Tennessee, Pleasant Lea came to Jackson County around 1850. He settled in the area then known as Big Cedar with his wife Lucinda, their nine children, and his brother. The Leas became respected members of the community; each served a stint as postmaster in the 1850s, and Dr. Lea acted as the town physician as well.

However, the Leas were slaveowners and consorted with other slaveowners – families like the Howards and Youngers.

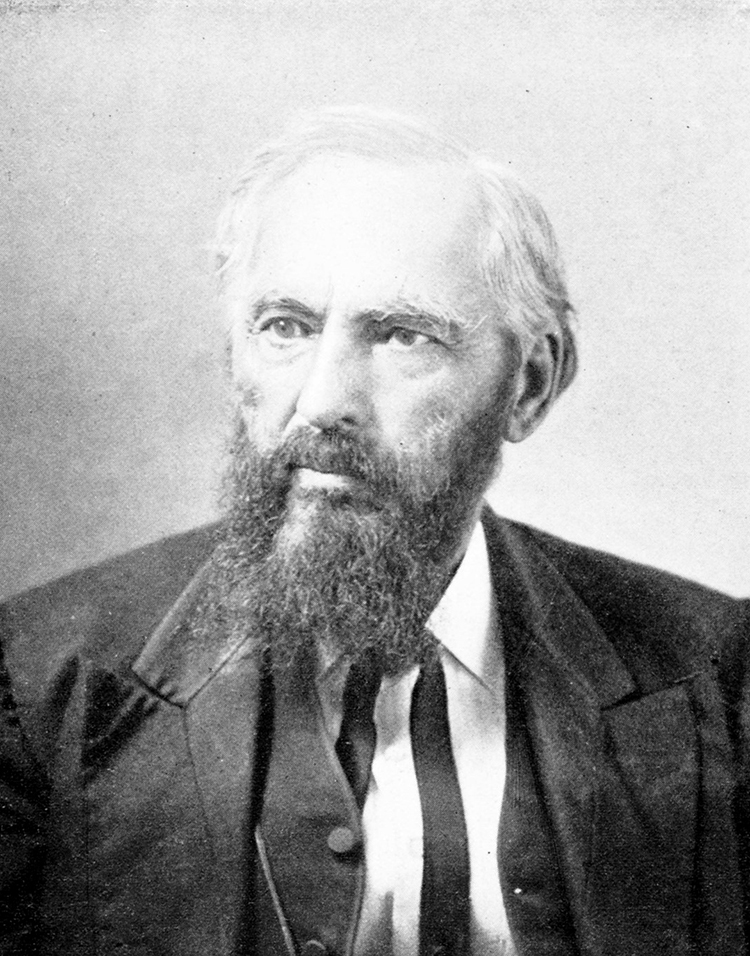

William Bullitt Howard, considered the founder of Lee’s Summit, joined the Leas in Jackson County. Howard had moved from Kentucky to Missouri with his wife Maria in 1844. In 1850, they purchased over 800 acres of land near Big Cedar, where they built a large Greek Revival style home and settled with their three children and 12 enslaved people.

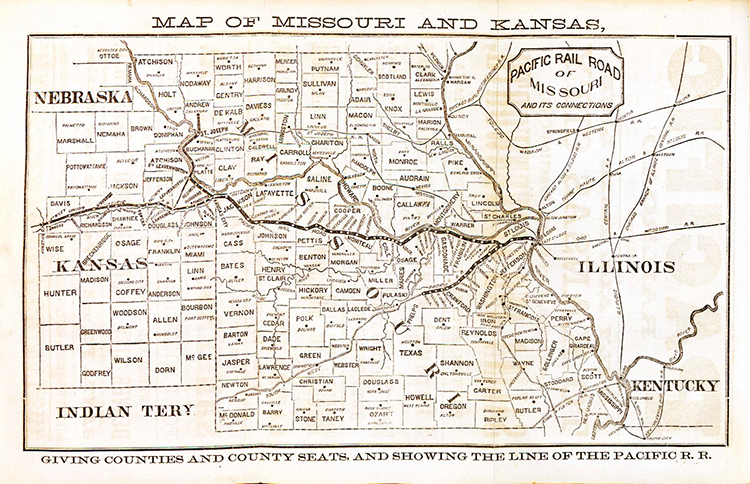

Howard came to Big Cedar in anticipation of the Pacific Railroad’s construction, which was planning a westward expansion connecting St. Louis to Kansas City. However, it would not be until 1865 that his vision for a new town on the railroad would be realized.

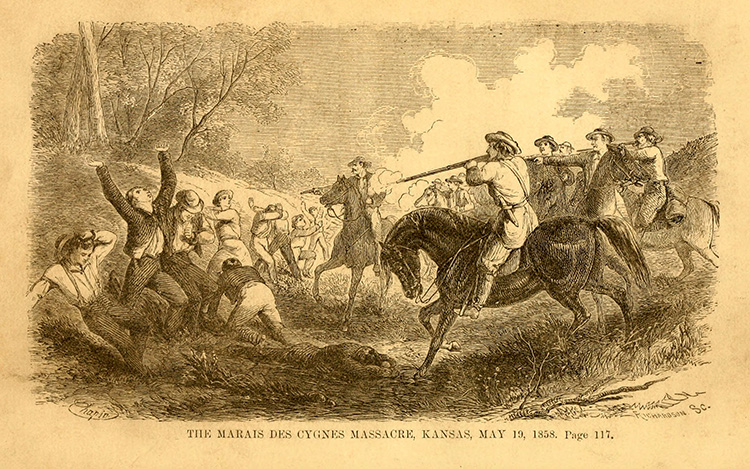

In the mid-1850s, tensions between anti-slavery “free staters” who settled in Kansas and pro-slavery Missourians erupted into violence. Confederate guerilla raiders recruited heavily from areas like Big Cedar where most residents were Southern sympathizers.

Confederate guerillas sabotaged the Union Army’s supply lines and frequently raided trains. Consequently, new construction on the Pacific line was halted during the Civil War.

Big Cedar became a hotbed of guerilla activity during the war years. Anti-slavery militias such as the Kansas Red-Legs and other Jayhawkers were suspicious of slave-owning families like the Leas, the Howards, and the Youngers.

Henry Washington Younger was a prominent local politician, judge, and an early resident of Big Cedar whose land abutted both the Leas and the Howards. In 1857, he and his family moved to Harrisonville but still found themselves frequent targets of pro-Union forces.

In the fall of 1861, Younger’s 17-year-old son Cole armed himself and went into hiding after a squabble with a Missouri militiaman. The following July, Henry was shot and killed while returning home from Westport. Believing that his father was killed by pro-Union forces, Cole joined a band of Confederate raiders led by William Quantrill.

Meanwhile, Pleasant Lea worried about the safety of his family.

Following the death of his first wife Lucinda, Lea remarried in 1860 to a woman from Massachusetts. Their marriage reportedly led to harassment by Confederate sympathizers. At the same time, the fact that he was a slave owner led to harassment by Union men.

By the time of Henry Younger’s murder, Dr. Lea had sent his youngest children to live with relatives in Tennessee, and his wife had fled the border violence and joined her parents in Ohio. Pleasant Lea was left alone to protect their home.

What happened next is disputed.

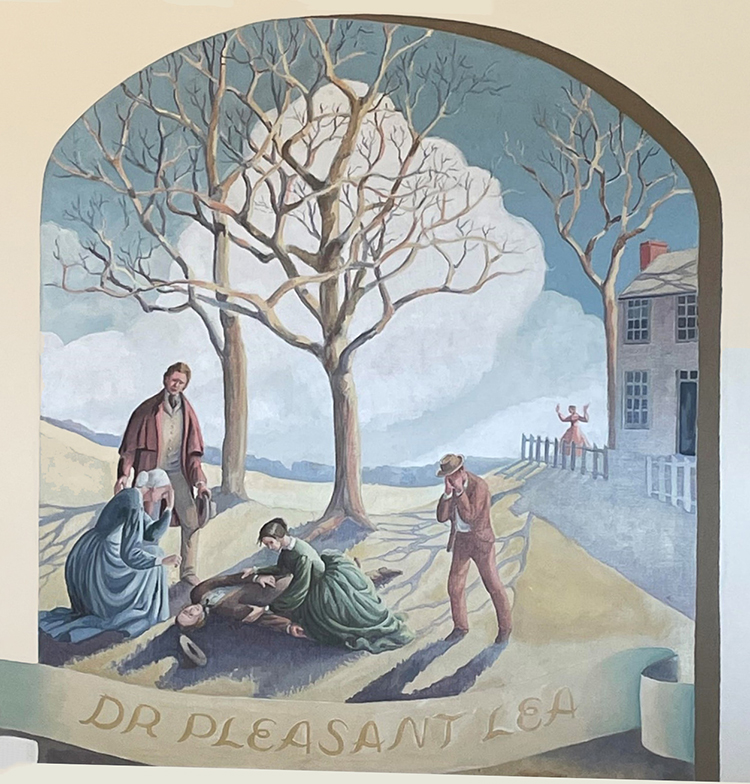

Dr. Pleasant Lea was killed, probably on September 12, 1862 – this is a matter of historical record.

By one account, Kansas Jayhawkers came to Lea’s home, lured him outside under the pretense of needing directions, and shot him in his front yard, while another account places Lea’s murder at the site of the future railroad depot.

Still another account claims that a messenger arrived at Lea’s home with news that his son, Joseph C. Lea, was injured while fighting alongside Quantrill and required medical attention on the other side of town, drawing Lea out into the open.

This last account is controversial among local historians, as it is often claimed that Joseph and his brothers enlisted with Quantrill’s men only after the murder of his father. Depending on which of these accounts one believes, Lea was murdered either because of his son’s involvement with Quantrill or because he was known to provide medical care to Confederate guerillas.

William B. Howard escaped the fate of his contemporaries. A month after Lea’s death, in October 1862, Howard was arrested as a Confederate sympathizer and imprisoned. He was released on a $25,000 bond under the condition that he and his family return to Kentucky.

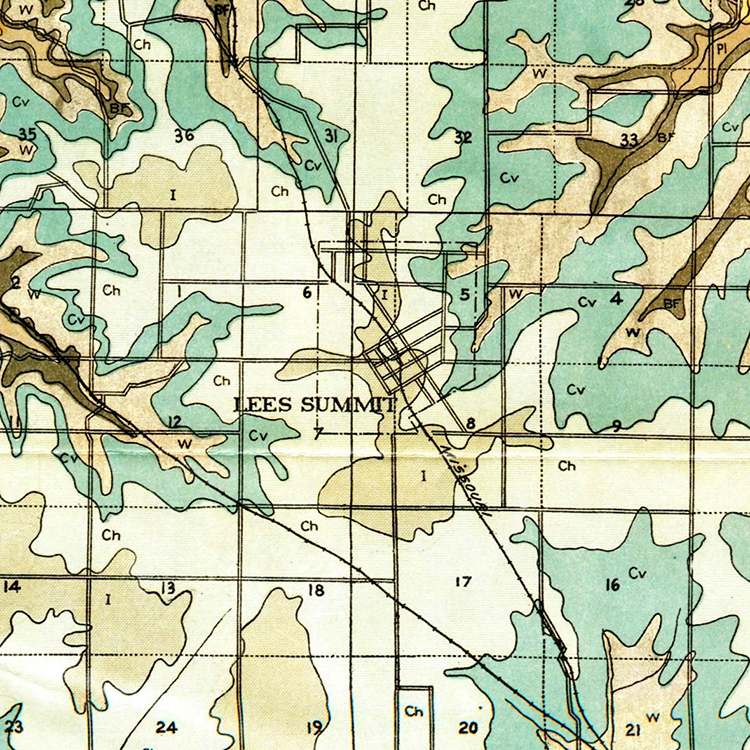

After the conclusion of the war in 1865, Howard returned to Jackson County and quickly filed a plat for the Town of Strother. He named his new town after his wife, Maria Strother, who had died during their exile.

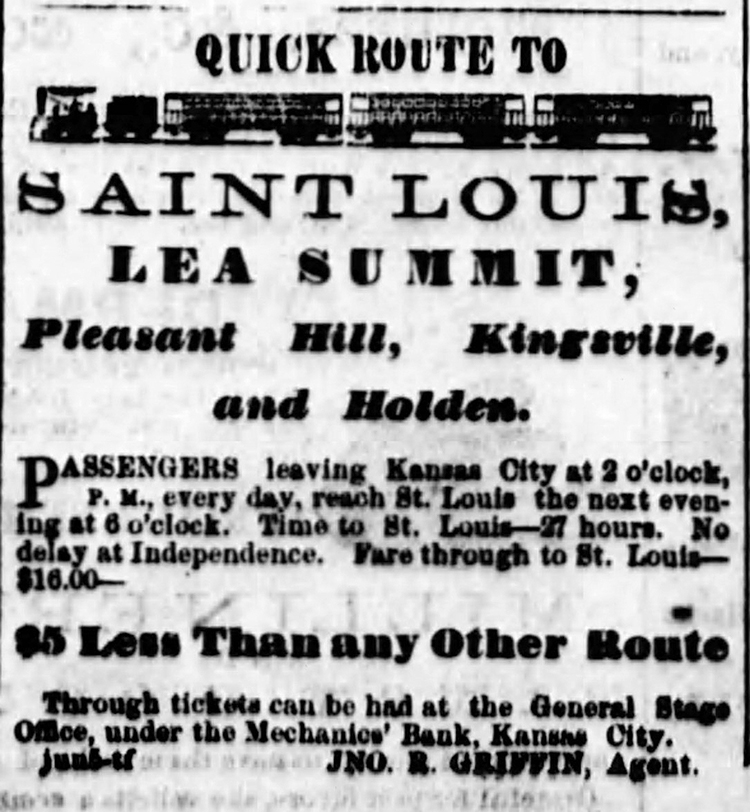

With construction renewed on the Pacific Railroad, Howard laid out downtown Strother along the railroad tracks. According to local historians, Howard soon changed the name of his town after learning of another town in Missouri named Strother.

In honor of his deceased friend, Howard incorporated the town in 1868 as Lee’s Summit—Summit in recognition that the town was the highest point on the Pacific line between St. Louis and Omaha, Nebraska.

Alternatively, the name may have come from the railroad surveyors who used the elevated farm of Dr. Lea to inspect the land. In both accounts, though, the use of “Lee” rather than “Lea” was the result of a simple mistake.

The accepted story is that Lee’s Summit was the misspelled name painted on a boxcar parked at the town’s first rail depot. The Pacific Railroad employee responsible evidently did not bother to consult with anyone as to the proper spelling of Dr. Lea’s name. After the initial mistake, no correction was made.

Evidence also points to an association between the area and Lea’s name even before Howard first platted the town of Strother.

In April 1862, five months before Pleasant Lea’s death, Brigadier General James Totten issued an order which addressed the “bands of desperadoes” who were known to and harbored by the farmers of “Doctor Lee Prairie,” as the town was also known. As further evidence of its shifting name, in the 1990s, local historian Donald Hale uncovered an 1865 handbill which advertised the land in Strother, “formerly known as Lee’s Summit.”

In the years after the Civil War, both spellings were used in advertisements and train maps. In Cole Younger’s autobiography, he variously refers to his childhood home as both Lea Summit and Lee’s Summit.

The accidental misspelling story remained unchallenged for over a century, until 1969. That year, The Kansas City Times ran an interview with a man who claimed that this story was “nonsense,” insisting Lee’s Summit was named for the Confederate general, Robert E. Lee. How did he know? William Bullitt Howard was his grandfather.

After a century of deception, William T. Howard, grandson of Lee’s Summit’s founder, decided it was time to tell the truth.

His grandfather had been an educated man, he told the newspaper, who would never have tolerated a spelling error in the name of his town. Furthermore, he stated that his grandfather had been a great admirer of Robert E. Lee and was happy to use the misspelling story as cover against post-war reprisals.

For over a century, the younger Howard claimed, the family had “quietly smiled” at stories about Dr. Lea and the boxcar at the depot. It was, he said, “a family joke.”

William T. Howard and his wife May, who later became president of the Lee’s Summit Historical Society, never wavered in their account. May Howard told The Kansas City Star in 1986 that the story about the misspelling was invented by a “Northern sympathizer.” In her mind, there was no doubt that the town was named for General Lee.

Local historians have largely dismissed the Howards’ claims, insisting that there is no evidence to support this version of events pointing to the area’s association with the Lea name prior to William Howard’s 1865 return from Kentucky. Furthermore, misspellings of Lea’s name were common both before and after his death.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.