The Heim legacy: What’s Your KCQ? investigates a Kansas City brewing tradition

Among the available libations at the J. Rieger & Co. distillery in Kansas City’s East Bottoms is a specially brewed lager, Heim Bier – a homage to a pre-Prohibition family brewery that once operated and thrived on the site.

A What’s Your KCQ? reader recently enjoyed a pour and inquired about the name. What’s the Heim history?

It traces to Austria, where Ferdinand Heim Sr. was born in 1830. He and his brother Michael were trained by their father as ropemakers, emigrated to the United States when Ferd was 21, and tried their hands at a number of ventures before purchasing a small brewery in Manchester, Missouri, near St. Louis.

They were part of a massive influx of German immigrants who settled in Missouri in the 19th century, drawn to the fertile land along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. Producing German lager proved to be a viable business. The Heims found their way to East St. Louis, Illinois, where they opened the Heim & Brother Brewery (later named the Heim Brewing Company). Michael passed away at an early age in 1883, and Ferd’s eldest son Joseph stepped into his uncle’s role.

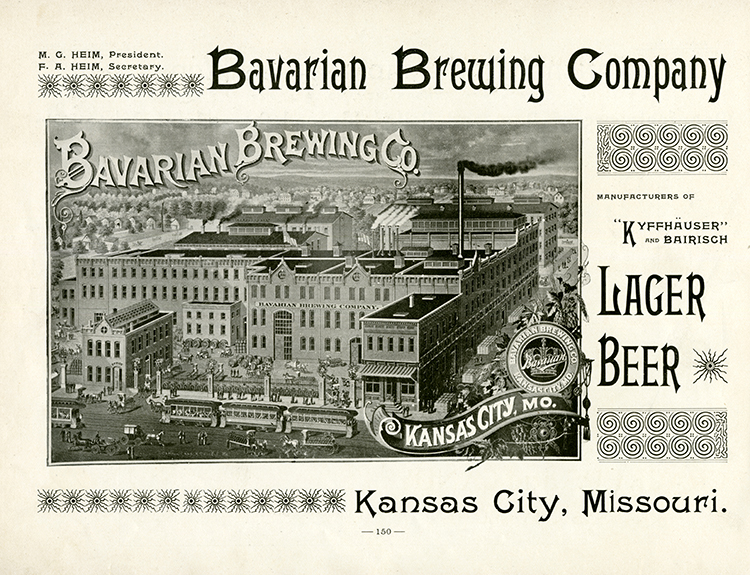

During a visit to Kansas City in 1884, Ferd purchased the Star Ale Brewery at 14th and Main streets to increase Joseph’s involvement and secure futures for his other sons, Ferd Jr. and Michael. Their new acquisition, then the largest brewing outfit in the city, was renamed the Bavarian Brewing Company.

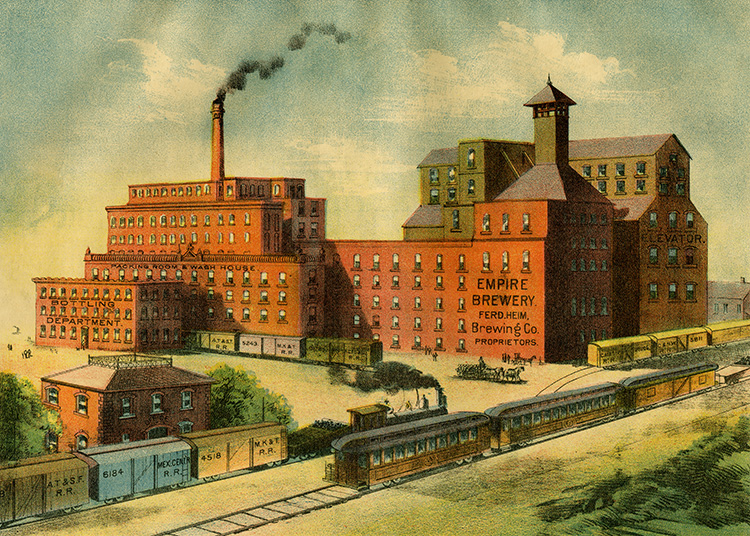

Kansas Citians welcomed Heim lager with open arms. In 1886, looking to expand operations in the city, the firm purchased an old sugar refinery in the East Bottoms near Rochester and Montgall avenues. Upon moving there, the family dropped the Bavarian name, rebranded as the Empire Brewery, and finally became the Heim Brewing Company when Ferd Sr. sold the family’s East St. Louis concern in 1889. Thereafter, Kansas City was the exclusive home of Heim beer.

After their father went into retirement, then passed away in 1895, the Heim brothers developed distinct and complementary business talents. Joseph kept the brewery running, Ferd Jr. managed expenses, and Michael had a knack for promotion. Of the family’s wealth, Michael was fond of saying “J.J. makes it, Ferd saves it, and I spend it.”

Michael used a variety of tactics to promote the brewery. The brothers invested in a professional baseball team, the Kansas City Cowboys, who played at League Park at Independence and Lydia avenues. The team turned in one losing season in 1886 before the National League kicked it out, citing a proclivity for rowdiness.

Later, the brothers built their own streetcar line powered by the brewery’s electrical generators. Beginning at Fifth Street and Grand Avenue, the Heim Line brought thirsty patrons directly to the brewers’ door. Ridership was slow, however.

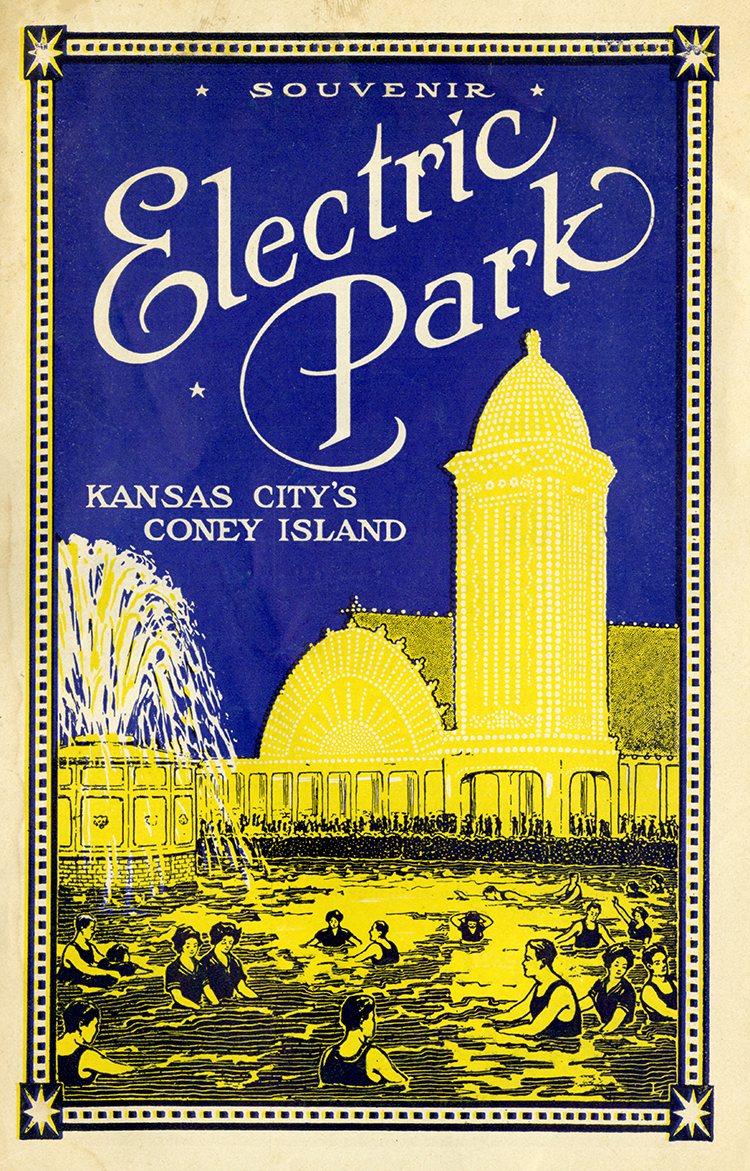

Michael schemed further. He had spent time in New York in his youth, and his love for Coney Island’s amusement parks inspired him to build a similar attraction.

Electric Park, named for the thousands of lights that illuminated its grounds at night, opened Sunday, June 3, 1900, on a narrow strip of land to the north of the brewery. It was an instant hit. Visitors streamed from downtown, filling streetcars headed for the park and clinging to the sides or climbing to the roof when room ran out.

The 17,000 people who showed up that first day found an array of wonders — a theatre for vaudeville and music shows, a cineograph theater for early motion pictures, a mechanical fountain from which performers would periodically emerge, and a beer garden supplied with Heim lager pumped straight from the brewery. A Ferris wheel and roller coaster came later.

Kansas City was in love with Heim beer, and business boomed. The brewery’s capacity when it opened was 12,000 barrels a year. Fourteen years later, in 1898, it was up to 120,444 barrels. Heim had become one of the most prominent brewers in the country.

Then, in 1905, the Heims acquired both the Rochester and Imperial breweries and rebranded as the Kansas City Brewing Company. Now capable of producing 350,000 barrels of beer annually, they rivaled the city’s other prominent brewing family – the Muehelebachs.

Their popularity wasn’t always unanimous.

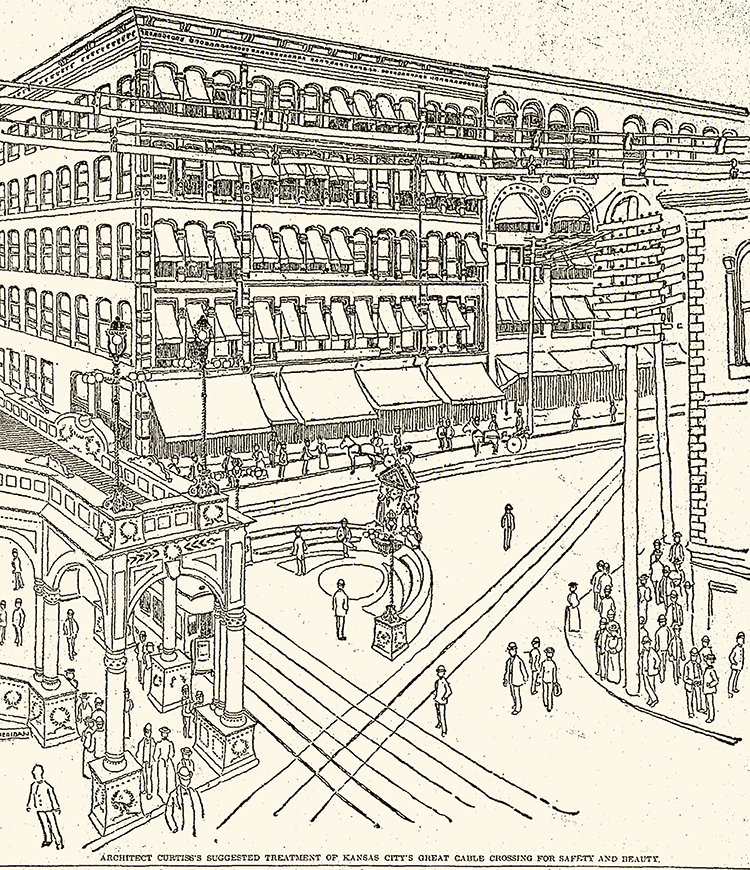

By the late 19th century, the junction of Main and Delaware at Ninth Street had become a jumble of intersecting street railway tracks. Waiting passengers stood on a triangle-shaped bit of pavement as streetcars and horse-drawn carts rushed past. On July 5, 1896, The Kansas City Star asked for a wealthy citizen to step forward and “enhance the public’s comfort and the city’s good looks.” The newspaper’s solution? A decorative refuge offering benches, lamps, and a fountain designed by architect Louis Curtiss.

The Heims – Joseph, Ferd Jr., and Michael – answered the call. To thank the city that nurtured their family business, they offered to bankroll the project, requesting only that the structure display a plaque dedicated to their recently deceased father. Curtiss gave his approval. All that was necessary for work to begin was the city council’s consent.

But a vocal group of detractors, made up of church leaders and temperance supporters, protested the memorial to a brewer and the measure failed to pass.

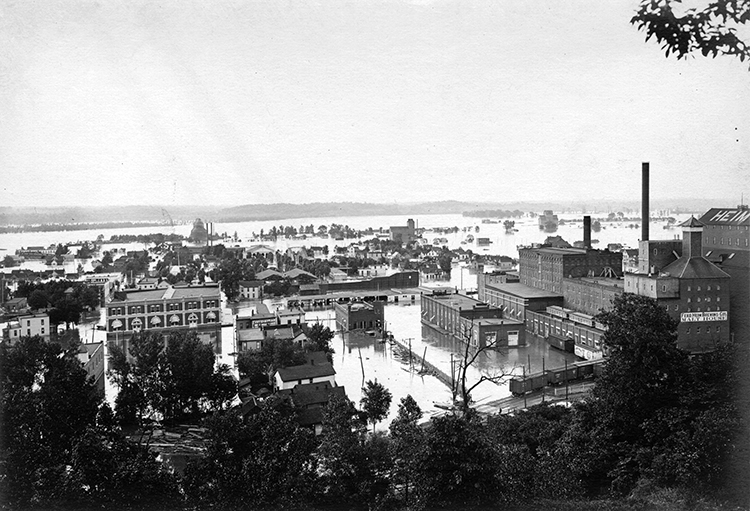

The brewery also experienced struggles. Labor disputes and periodic fires slowed production. In May 1903, the swollen Missouri and Kansas rivers overflowed their banks and flooded low-lying portions of the city. The city’s river bottoms were hardest hit, water inundating areas where many Heim customers lived and worked and drenching the brewery’s bottom floors and Electric Park.

The brewery stayed put, but the brothers decided to move Electric Park south to a site along Brush Creek, near The Paseo, and sold their streetcar line. The second Electric Park opened in 1907 with all the attractions of the original and many more. One thing was lacking, though – beer.

Like the memorial to Ferd Sr. years earlier, the move south to a genteel, saloon-free suburbs sparked public protest. The Board of Police Commissioners refused the new park’s liquor license application.

Prohibition took effect in 1920 and outlawed all large-scale brewing operations in the country. The Heim brothers sold their facility in the East Bottoms to other firms and concentrated on other business interests.

The second Electric Park kept revenue coming in, but fires in 1925 and 1934 led to its closure. Joseph Heim passed away in 1927. Michael followed in 1934. Finally, Ferd Jr. died in 1943. And the family faded into the city’s memory.

But traces of the Heim legacy are still around — if you know where to look.

During his boyhood days, Walt Disney visited the second Electric Park often. Later, he credited “Kansas City’s Coney Island” as an inspiration for his theme parks.

Ferd Sr. and his sons built homes along the city’s fashionable Benton Boulevard that still stand today. Many of the brewery buildings remain in the East Bottoms as well. The Kansas City Parks and Recreation Department maintains Heim’s Electric Park – with a playground and athletic field – on the site of the old amusement park.

In 2018, J. Rieger & Co. converted the old Heim bottling plant into a new home for its distillery. And in 2021, it opened the Electric Park Garden Bar, where our reader enjoyed a Heim Bier, brewed for the distillery by KC Bier Co., the local keeper of the German brewing tradition.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.