Who were the Muehlebachs and why is their name everwhere? KCQ investigates

In a recent article about the history of Municipal Stadium, we learned that the former home of the Kansas City Athletics and first home of the Royals and the Chiefs was originally called Muehlebach Field. We also learned that it was named after Blues owner, George Muehlebach Jr.

A reader noticed the same name on a downtown hotel sign and asked What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to explain who the Muehlebachs were.

The family patriarch, George Muehlebach Sr., was born in Aargau, Switzerland, in 1833 and emigrated to the U.S. in 1854. Starting out in Lafayette, Indiana, he and three brothers — John, Peter, and Francis X. — eventually found their way to the bustling town of Westport, Missouri.

George Sr. first gave the saddle and harness business a try. The constant coming and going of carts laden with trade goods later inspired him to enter the overland freight business. Still dissatisfied, he left for Colorado hoping to strike it rich in mining.

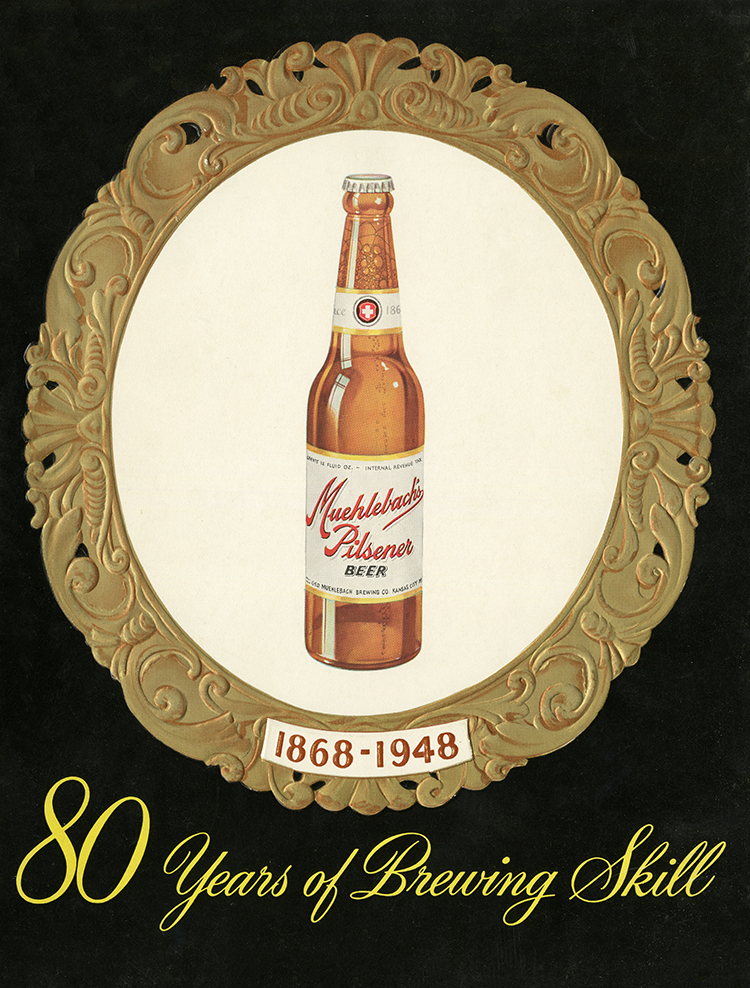

He returned to Kansas City in 1868 and, with help from his brother John, purchased a small brewery situated near a natural spring at 18th and Main. As a nod to their Swiss heritage, the country’s flag was chosen for the company logo.

The Muehlebachs had found their calling, and the brewery was soon producing nearly 4,000 barrels of beer annually. But they didn’t rely exclusively on that. Diversification became a key to the family’s success and ability to endure tough economic times.

The Muehlebachs also got into the hotel and grocery fields. Peter started a wine vineyard near 41st Street and State Line Road. And George Sr. began trading in downtown property, his holdings managed by the Muehlebach Estate Company.

In 1880, a new brewery building was constructed at 18th and Main. The ornate structure was nicknamed Beer Castle by locals due to its Romanesque revival architectural flourishes.

John died that year and George took over as the brewery’s sole operator. Eventually, George Sr.’s sons George Jr. and Carl began working for their father. By 1886, the brewery had grown production to 30,000 barrels a year.

In addition to beer, the Muehlebachs shared a love of baseball. Business was booming, and to spread the word, George created his own team — the Muehlebach Pilseners. While learning the family business, George Jr. played as the first baseman.

When George Sr. died in 1905, his sons took over the business. They also inherited the Muehlebach Estate Company and continued to prosper in land ventures.

By the eve of national prohibition in 1920, the brewery had exceeded production capacity of 300,000 barrels of beer annually. Fortunately, the family’s other investments kept them afloat when the country went dry.

In 1915, the Muehlebach family got into the luxury hospitality business, building a state-of-the-art hotel at 12th Street and Baltimore Avenue. Over the coming decades, the Hotel Muehlebach hosted celebrities and visiting U.S. presidents.

The brewery also began producing non-alcoholic malt beverages for those still desiring a cold one — and one that was legal.

Building on his love of baseball, George Jr. purchased the minor league Kansas City Blues in 1917. He bought a plot of land at 22nd Street and Brooklyn Avenue and built the team a new stadium. Muehlebach Field opened in 1923 and was also home to the Negro Leagues’ Monarchs and the National Football League’s Cowboys. When Muehlebach sold the Blues in 1933, the new owners changed the name to Blues Stadium. Then, when the major league Athletics moved to Kansas City, the 32-year-old facility was upgraded and renamed Municipal Stadium.

In a “wide open” town like Kansas City where prohibition laws were loosely enforced, production of beer-like malt beverages didn’t keep the brewery afloat. The Muehlebachs held onto the building at 18th and Main but, by 1930, the family was out of the beer making business.

Prohibition ended in 1932 and with their brewing facility intact, the Muehlebachs decided to make a return. They were counting on Kansas Citians’ desire to enjoy an ice cold Muehlebach beer after several years of drought.

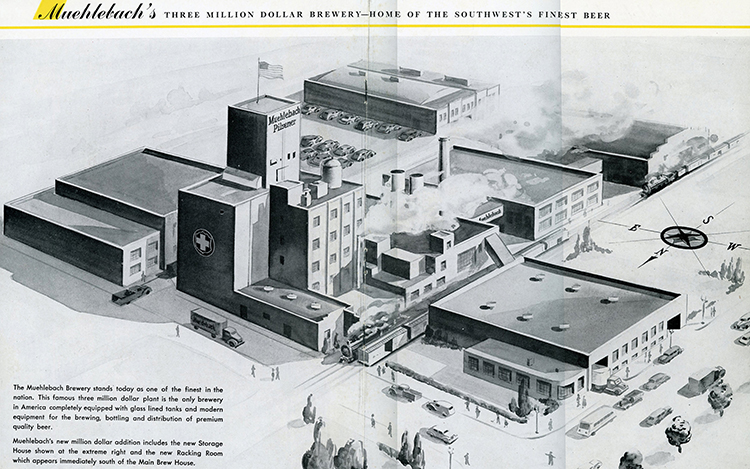

The brothers failed to revive the old brewery, but George Jr. eventually attracted enough outside investment to construct a new one at Fourth and Oak and outfit it with the latest in brewing technology. George Jr. became vice president of the new company.

The move worked out, at least initially. Despite supply shortages of every kind during World War II, the company expanded. Additions were made to the plant, aimed at increasing capacity. The brewery also began venturing into new markets outside the Kansas City area.

But sales began to slump by the late 1940s. Other brands had moved into the Kansas City market and in 1955, when the major league Athletics came to town, they were sponsored by Schlitz rather than the hometown brand. Carl passed away in 1946, followed by George Jr. in 1955. The end came in 1956 when Schlitz purchased Muehlebach brewery and closed the facility in 1973.

The Beer Castle was razed in 1941 and replaced by the Trans World Airlines building. Municipal Stadium, once named for the family, was torn down in 1976 after the Truman Sports Complex was opened.

Although the Muehlebachs’ first brick brewery and sports stadium are long gone, traces of the family’s legacy can be found.

From 2009-13, the Boulevard Brewing Company produced Boulevard Pilsner using the Muehlebach recipe and label design. The brewery also named its private event space the Muehlebach Suite.

Kansas Citians may remember Muehlebach & Sons grocery stores across the metropolitan area. The final remnant of the family’s grocery business, which started in the 1870s, slipped away when the Apple Market in Parkville, Missouri, closed in 2003.

A handful of the brick buildings from the brewery at Fourth and Oak survive and are occupied by an assortment of River Market businesses. A distant ancestor of George Sr. opened Muehlebach Funeral Care on Troost Avenue in 1954.

And there’s the old hotel.

In 1962, the last surviving heir to the Muehlebach Estate Company sold the long-term leasehold on the hotel to a group of property investors. The site was marked for redevelopment and portions of the building were lost to make way for the Muehlebach Convention Center. What survives of the original Hotel Muehlebach is now part of the Kansas City Marriott Downtown hotel complex.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.