KCQ: What happened to Kansas City’s downtown sports stadium?

Kansas Citians have a lot to say – and feel – about the Kansas City Royals’ interest in relocating Kauffman Stadium. Particularly touchy is the idea that its new home could be downtown.

Some say the economic benefits a downtown baseball stadium would generate is a no-brainer. Others think the team should stay put and suggest that complications like increased downtown traffic would make the move a disaster.

A recent article covering the potential move mentioned that both the Royals and the Kansas City Chiefs once played in a facility near downtown. A reader asked What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to investigate the history of Kansas City’s first major sports venue, and whether its location worked for fans.

By the late 19th century, dozens of amateur and semi-professional baseball teams called Kansas City home, most sponsored by businesses, schools and clubs. Teams representing the city’s disparate communities would find a relatively flat patch of ground and enjoy a quick game in their off time.

Baseball professionalized in Kansas City when the Blues became one of the founding teams of the minor league American Association in 1902. Association Park, a grandstand flanked by two sets of bleachers at 20th and Olive streets, was the club’s first home.

Despite baseball’s popularity, the team struggled to grow a fanbase.

But that began to change in 1917 when beer baron George Muehlebach purchased the club. He had fond memories of spending his teen years playing for the company team attached to his father’s brewery, the Pilsners, and wanted to leave his stamp on the sport.

To attract fans, Muehlebach promised a new stadium and chose a site at 22nd Street and Brooklyn Avenue.

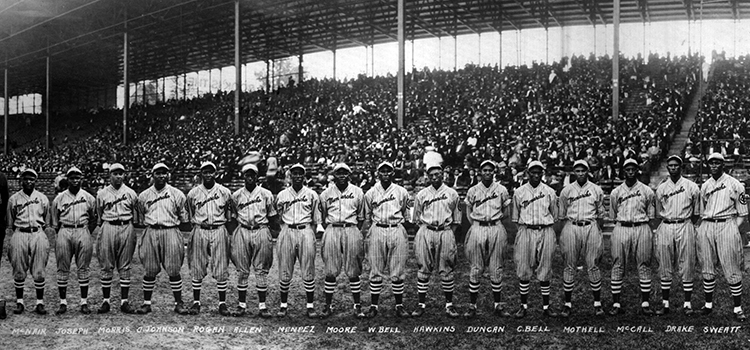

In 1920, a few years before the new stadium opened, the Negro National League was founded, and with it, the Kansas City Monarchs. Thanks to stars like Bullet Rogan and Frank Duncan, the team was an immediate hit with fans – more so than the existing teams.

While the Monarchs to play at Association Park with segregated seating for fans, some worried the invitation wouldn’t extend to the new stadium.

Muehlebach Field’s single-deck grandstand with seating for about 16,000 fans opened on July 3, 1923. The organization calmed fears over the future of Black baseball when it announced that the Monarchs could play their games in the new facility. Black fans could attend Blues games as well, although the stands would continue to be segregated.

That is, until 1933. That year retired Major Leaguer Johnny Kling purchased the Blues. He removed the “colored section” signs that had kept Black and white baseball fans separated.

Kling’s policy stayed in effect until he sold the team in 1937, this time to New York Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert, who reposted the signs for the 1938 season. The Call’s sports editor published an open letter to the new owner asking him to take a “cosmopolitan view” of the seating policy and reminding him that Black and white fans had been sitting together at Monarchs games without incident long before Kling came to town.

Ruppert ignored the plea, resegregating Ruppert Stadium, which later changed to Blues Stadium.

The Blues left town in 1954. That same year, the Philadelphia Athletics relocated to Kansas City.

To prepare for the city’s first Major League team, the facility rebranded to Municipal Stadium and received a much-needed facelift. Prior to opening day, April 12, 1955, workers rushed to rebuild the stands, toiling through the winter to complete a roofed second deck and increase the stadium’s capacity to around 31,000.

The Monarchs only spent one season in the updated facility before a new owner moved the club to Grand Rapids, Michigan.

In 1960, Charlie Finley purchased the Athletics. And Finley had a knack for attracting attention.

Local fans may remember the petting zoo near an outfield wall, or Finley’s habit of riding the team mascot, a Missouri mule named Charley, around the field on gamedays. And then there was the fence he built in the outfield that matched the dimensions of the smaller Yankee stadium, so his players — theoretically — could hit more home runs.

However, Kansas City and the Athletics weren’t meant to be. Finley took his team to Oakland, California, in 1967.

But by that time, the stadium already had another occupant. In 1963, Dallas Texans owner Lamar Hunt brought his American Football League club to Kansas City. Winning helped, but the newly branded Chiefs also put in the work to attract fans and establish a home for its Wolfpack Fan Club in the stands at Municipal Stadium.

Then, in 1969, Ewing Kauffman secured a Major League expansion franchise, and the Royals were born.

One building housing two professional sports teams was a tight fit, though, so the city began to scout more spacious accommodations.

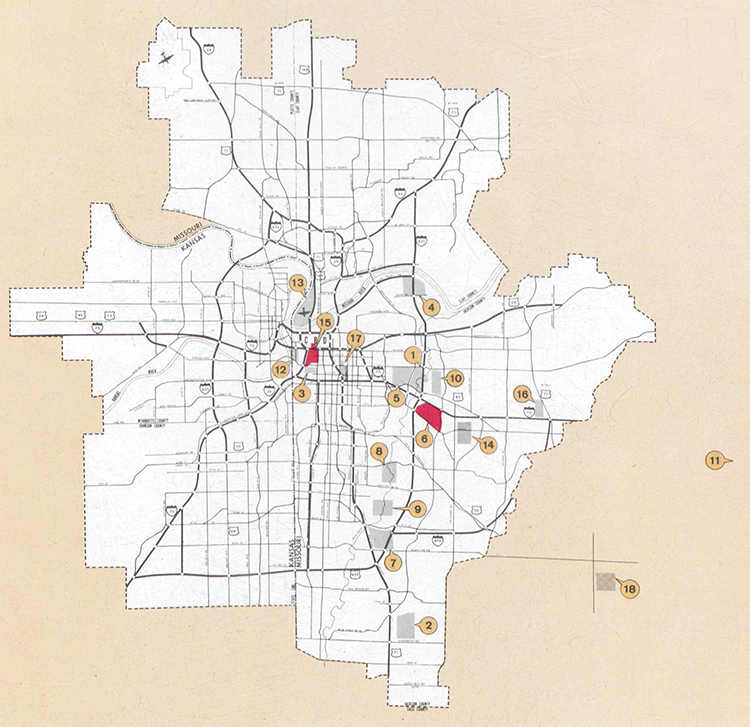

In the 1950s, a site along the Missouri River east of the Armour-Swift-Burlington Bridge looked like a winner. The city purchased the land but lost momentum, and redevelopment along the riverfront didn’t move forward for decades.

Once the “urban renewal” era was in full swing, developers began eyeing possible downtown stadium locations closer to the central business district, like where the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts and Hy-Vee Arena sit today.

Eventually, they chose a location east of the city near the old community of Leeds.

Developers acknowledged the benefits a new downtown stadium could have had for the city, but ultimately the low cost of the Leeds site, its easy highway access, and its ample space for parking lots, won them over.

The Truman Sports Complex opened in 1972 with separate state of the art facilities for the Chiefs and the Royals.

Many failed to mourn the demolition of Municipal Stadium in 1976, but nostalgia for what was lost has grown with time. Those who sat in its stands tell about arriving there on public transportation or by foot. They talk about sitting so close to their favorite players that they could almost reach out and touch them. They recall the Monarchs marching through the neighborhoods surrounding the stadium in the annual opening day parade.

And, of course, they remember the barbecue.

Broadcast coverage of Blues games at Municipal Stadium is one of the ways Kansas City came to be known as the barbecue capital of the world. With Kansas City’s foundational barbecue restaurants all operating in the vicinity of the stadium, the aroma on gameday was an olfactory treat. Fortunately, this tradition followed the teams to the new stadiums in the form of tailgate parties.

If the Royals do relocate to downtown, a long history of lessons learned is ready to guide them.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.