The Plaza Flood — KCQ Investigates a 1977 Disaster

Strings of colored lights have been going up on the Country Club Plaza in preparation for the annual Evergy Plaza Lighting Ceremony, and on Thanksgiving night, the holiday season will officially get underway with the flip of a switch.

Seasonal traditions on the Plaza are a cornerstone of Kansas City culture; without them, the city wouldn’t be the same.

After reading our recent 1951 flood story, a reader thought about what it would mean if a flood hit the shopping district. She asked “What’s Your KCQ?,” a collaboration between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library, about the 1977 flood that damaged the Plaza and other parts of town.

Late summer of that year was like many others on the Plaza. Free outdoor concerts along Brush Creek attracted large crowds to hear the likes of Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington and the Kansas City Philharmonic, and merchants prepared for the busy shopping season to come.

Around midnight on September 12, 1977, heavy rain began and persisted into the morning. By the time a second wave of storms hit that evening, the ground was saturated. Sixteen inches of rain fell that night.

In spite of a flash flood warning, Plaza nightlife continued. Then Brush Creek began to overflow its banks.

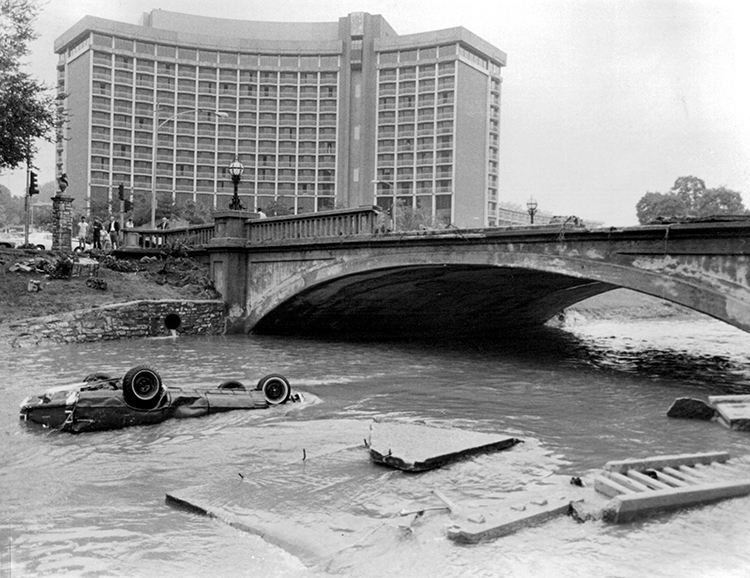

What was later described as the worst rainstorm in the city’s history sent five feet of water rushing over Ward Parkway. A bartender at the Plaza III told The Star, “There were cars floating by windows, with people in them, and still there were folks sitting there eating dinner.” Others raised toasts to the flood waters outside. It took the water pressure bursting the restaurant’s doors for the diners to finally escape from the back entrance.

The water rose so suddenly that 385 people attending a concert at the Alameda Plaza Hotel had to be evacuated in a foot of standing water. The first floors of the department stores along Ward Parkway and Nichols Road also flooded, and the current in Brush Creek was so strong that it tore away portions of its concrete lining and deposited them downstream.

A damaged gas main somehow ignited, and the resulting explosion started fires in buildings along the 600 block of W. 48th Street. Witnesses later described a scene that looked like the aftermath of an air raid.

By water or by fire, 77 of the 155 Plaza businesses were damaged that night.

Once the rain stopped, locals surveyed the damage. Some took the opportunity to swim down flooded streets. Others grabbed retail goods floating in the current.

Many wondered how this could have happened.

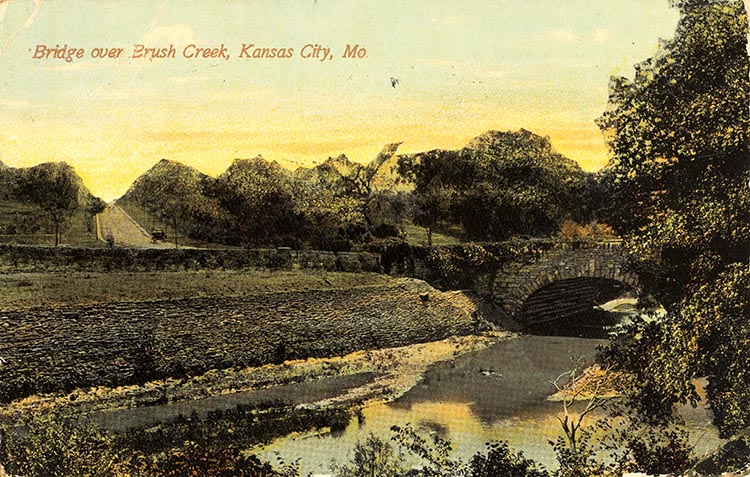

To maximize real estate along its north bank, Plaza developer J.C. Nichols rerouted it. Still subject to overflows, in the 1930s, the city approved a plan to the creek to ease drainage into the Blue River to the east. Workers poured tons of Pendergast Ready Mix Concrete into the streambed to create a massive, open storm drain.

Additionally, 1920s-era sewers weren’t designed to channel the amount of run-off the heavily-paved Plaza could generate during a massive storm.

However, decades passed and the system seemed to work. Developers were happy to sacrifice the stream’s once rustic charm to alleviate the constant fear that it would overflow and flood Plaza businesses.

But the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers may have foreseen disaster.

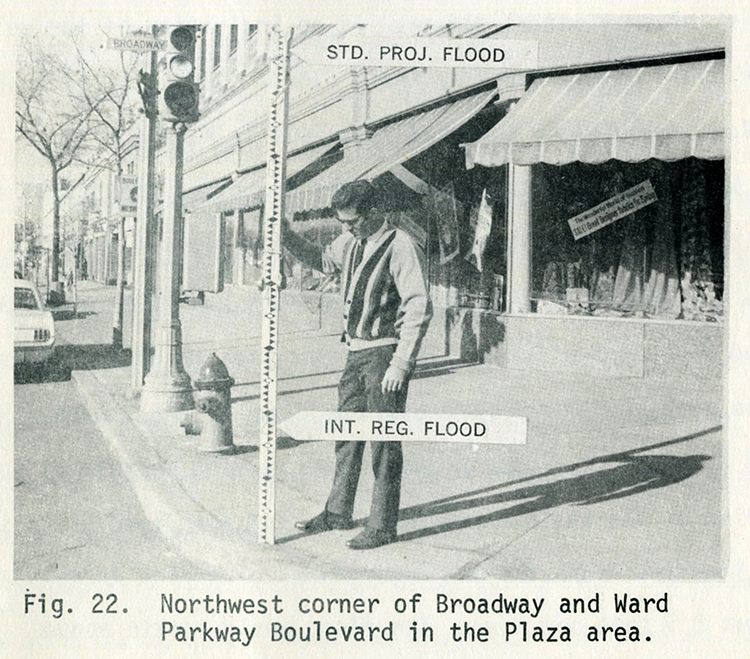

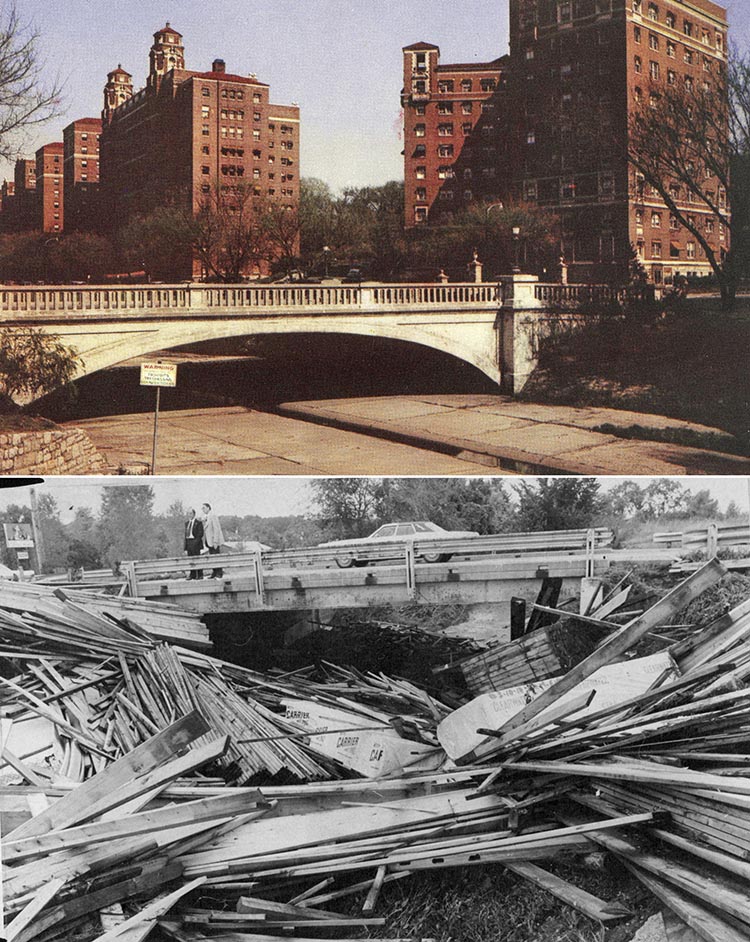

In a 1970 report, the Corps warned that Brush Creek could reach flood state in under an hour in the event of heavy runoff. And the ornamental bridges along the stream wouldn’t help matters. Designed with an eye toward aesthetics rather than flood management, these low structures created choke points where flood debris could accumulate to form dams.

All told, the 1977 disaster claimed 25 lives and caused over $100 million in damages. It was the worst flood to hit Kansas City since 1951.

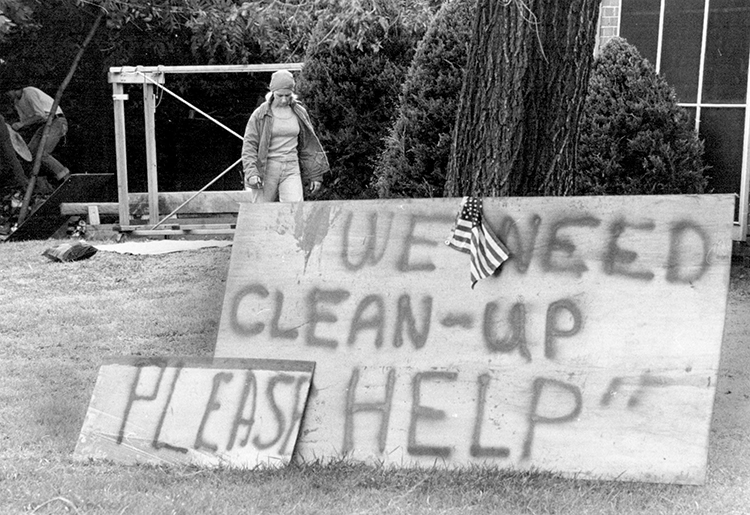

Local authorities declared a state of emergency to speed the arrival of federal relief funds for victims. The Parks and Public Works departments got busy restoring landscaping along the creek and making bridge repairs. Temporary workers and city employees assisted with the Plaza cleanup.

As the work continued, the Plaza Art Fair — A marker of fall in Kansas City — went on as scheduled. And by Thanksgiving, the lights were up and ready for the annual ceremony. Just a couple weeks later, most of the 77 damaged businesses had reopened. That day, The Star praised the speed and efficiency of the city’s 80-day Plaza recovery project.

However, the Plaza was not the only area to flood. Speed and efficiency did not define disaster recovery to the east and elsewhere.

By December, more than 300 families living downstream of the Plaza remained stranded in temporary housing. Led by Councilman Bruce R. Watkins, property owners called out City Hall for the unevenness of its response.

A Southwest Boulevard business owner whose building was damaged when Turkey Creek flooded during the same storm event, told The Star, “I went out to the Plaza last night and the city was washing down tennis courts … and down here we’re up to here in mud.”

In addition to a slower response from the city, victims found the mountains of paperwork needed to apply for federal assistance daunting. Later, when testifying before Congress, Emanual Cleaver II compared the task to “writing a short novel.” The hearings resulted in a flood control plan, but stakeholders east of the Plaza weren’t comforted when the first draft called for their communities to be permanently evacuated.

Later, largely thanks to the advocacy of community leaders like Watkins, Cleaver, and many others, an amended Brush Creek Flood Control and Beautification Project — locally known as the “Cleaver Plan” — was approved. The stream was deepened and widened to ease water flow, and bridges were upgraded and replaced to remove choke points.

Back on the Plaza, many bemoaned what the flood erased. The cleanup and rebuilding began a transition away from its neighborhood shopping center feel toward a focus on high-end retail and fine dining.

Critics of the project point out that floods have damaged property east of the Plaza since it was completed. Supporters point out that the damage would have been far more severe without the modifications. It may take another storm like the one that hit in September 1977 to truly measure the project’s success.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.