Rivers rise: KCQ examines the 1951 Flood

Seventy years ago this month, Kansas City was hit with a natural disaster that reverberates to this day – resurfacing in a recent query to “What’s Your KCQ?”:

“What happened during the 1951 Flood?”

From May through July, monthly rainfall totals in Kansas and Missouri were three to four times higher than usual. Locals joked about building arks, because in some areas it had literally rained for 40 days and 40 nights. Between July 9 and July 13 alone, parts of the Kansas River basin received 18.5 inches. Unable to absorb any more water, the Kaw began to overflow.

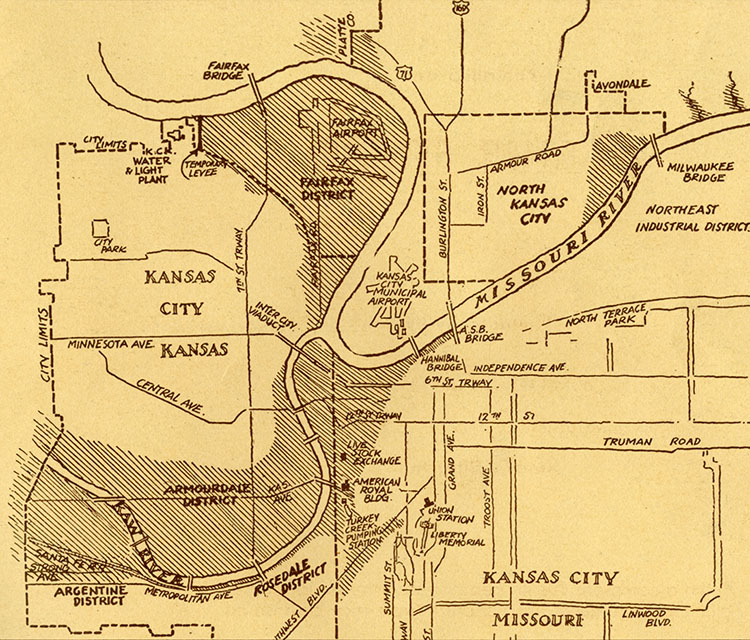

Flooding started above Manhattan, Kansas, and moved east through Topeka and Lawrence, inundating thousands of homes, businesses, and farms as it headed for the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers between Kansas City, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had spent weeks reinforcing the levees upriver from Kansas City, and assured the public they would hold. But on the morning of July 12, as the Kansas River crept ever higher, officials began to plan for the worst. Residents in the vicinity of the dikes were warned to prepare to evacuate. Sewers on both sides of the state line began to back up, leaving water standing in low-lying streets and covering railroad tracks.

Around 10 p.m., the evacuation order sounded for southern KCK. Shortly thereafter, water began pouring over the 40-foot-tall levees, first in the Argentine neighborhood, then in Armourdale. When dawn broke Friday morning, both had become one giant lake.

As the day wore on and the water continued to rise, events happened in quick succession.

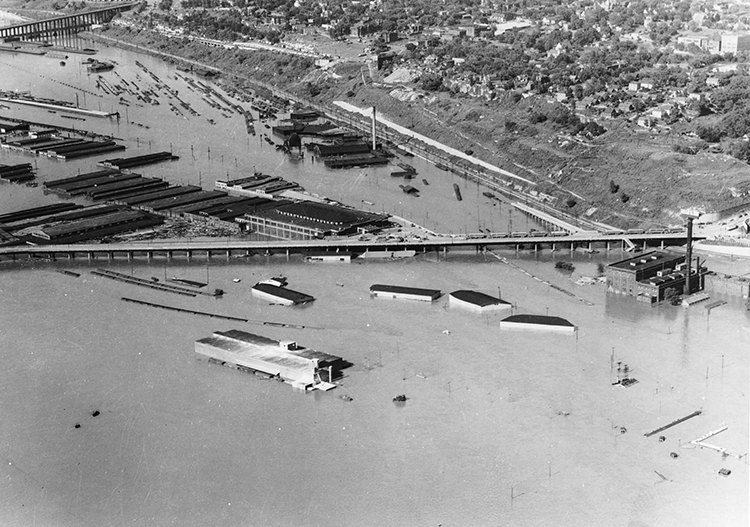

Municipal Airport (now the Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport) was still dry, but no one knew how long that would last. Across the confluence on the Kansas side, water was rising fast around the Fairfax Airport. Pilots from both sites flew their planes to safety in Grandview.

In the West Bottoms (then called the Central Industrial District), there was a scramble to outrun the surge. Stockyards staff herded as many animals as they could into overhead chutes. Workers raced to move equipment, goods, records, and supplies to upper warehouse floors.

Nearby, water was inching up Southwest Boulevard. Firefighters were deployed to the Turkey Creek pumping station and tried desperately to keep the engine room dry. According to the official Kansas City Fire Department report, Capt. Guy Mills volunteered to be lowered down a 22-foot shaft to close underground floodgates, a route already compromised by water and dangerous electric cables. Mills’ heroics were successful, but it was too late.

A boy rushed into the station with news that a dike had broken. The firefighters were forced to abandon their efforts. The building was soon under water, and the engines stopped. Since the Turkey Creek station supplied about two-thirds of KCMO’s water, water pressure plummeted all over the city.

Sirens, horns, and shouts to evacuate rang out in the West Bottoms and Southwest Boulevard areas all morning, but the speed of the flooding caught everyone off guard. Boats, canoes, and rafts were deployed to rescue people who were trapped in homes and businesses and on rooftops.

Sandbags, broken concrete, mounds of dirt and rocks from local quarries, and junked cars were used to shore up the levees protecting Municipal Airport and North Kansas City. City leaders worried about how much of water the Missouri River could absorb from the Kaw. They ordered residents to evacuate.

Around noon, Kansans who had made it to work in downtown KCMO were urged to return home in case the bridges were washed out. Auto traffic on the Intercity Viaduct (today’s Louis and Clark Viaduct) jammed and came to a standstill. On the bridge’s sidewalks, pedestrians ran.

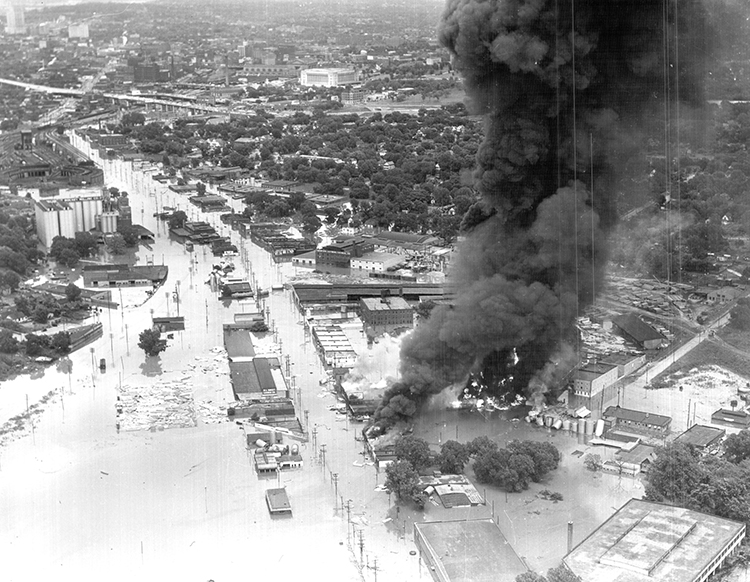

Adding to the chaos, fires broke out along Southwest Boulevard shortly after 1 p.m. Tanks of oil, gasoline, and other flammable liquids had broken free of their supports and were floating around the area near 31st Street and Roanoke Road. Oil shimmered off the floodwaters. A spark ignited one of the tanks, and massive clouds of black smoke began billowing into the air.

Firefighters were again dispatched to the area. Forced to battle from a distance, they filtered and drafted floodwater to subdue the flames. But each time they managed to contain one fire, another tank would explode, and they would have to begin again. All told, it took 425 firefighters more than three days to extinguish the blazes. Fifteen men were injured, but no deaths were reported.

In Kansas, the Fairfax District was gradually being swallowed by water. Attention turned to protecting the Board of Public Utilities power and water plant in Quindaro along the Missouri River. The plant supplied electricity and water to 130,000 residents in Wyandotte and Johnson counties.

A temporary levee was thrown up around the plant. Approximately 500 city employees, volunteers, and National Guard members worked from Friday afternoon through the night, trying to hold back the advancing water. Concerned the barrier would not hold, the plant manager ordered two more levees built closer to the plant as backups.

A similar emergency levee was constructed on the Missouri side. The East Bottoms pumping station (located where Nicholson and Indiana avenues used to intersect) was now suppling water to the entire city, and protecting it was a top priority. In addition to the levee, men were positioned every 1,000 feet along the Missouri River from the Kaw to the Blue River. They were directed to report weak spots in the flood wall, or potential threats to the pumping station. Luckily, the levees held.

Residents were urged to conserve water as much as possible. The city manager ordered taverns, theaters, and nonessential retail and service businesses to close for the duration of the shortage. Public water stations were set up in neighborhoods that had completely lost service. Police patrolled the city, citing those who insisted on washing their cars or watering their yards.

Worried about disease, health officials recommended that anyone who had been in contact with the floodwaters immediately start a course of typhoid shots. Clinics popped up in hospitals and along the west side of town. Housewives in neighborhoods where water was still running were told to boil it before drinking or cooking.

The Kaw crested at about 50 feet around 3 a.m. on Saturday, July 14. The Missouri River crested at approximately 36 feet. The Corps of Engineers confirmed a few hours later that the water was beginning to drop, though progress was slow. Cleanup efforts could not begin in earnest until Tuesday, July 17. The next day – thankfully – the Turkey Creek station resumed partial operations. Restrictions on water usage began to ease.

The cleanup took months. Muck, mud, and debris were everywhere. In the Stockyards, more than 5,000 head of livestock had drowned. The overwhelming stench lingered for weeks, and health officials had to routinely remind Kansas Citians that the odor did not carry any disease.

Remarkably, the loss of human life was not worse. Five people reportedly died during the flooding.

Financially though, the cost was enormous. The combined damage along the Kansas River basin and Missouri River was over $800 million. Today, that toll would be more than $8 billion.

The lasting repercussions of the flood were disparate. Much of KCMO had struggled with the immediate water shortage, but it was a grimmer and longer-lasting story on the west side and in KCK. Affected neighborhoods were home to blue-collar workers, most of them Hispanic. The livestock and meatpacking industries of the West Bottoms and Armourdale never fully recovered. Many residents lost both their homes and jobs and were forced to leave.

Yet in terms of flood control, the events of 1951 prompted effective changes in the Kansas City area, particularly along the Kaw. A series of 18 dams and water impoundment reservoirs soon sprung up on the river. During the massive flooding of the summer of 1993, those structures were credited with protecting thousands of acres from damage.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.