Art in the Archives: The Legacy of William Weber

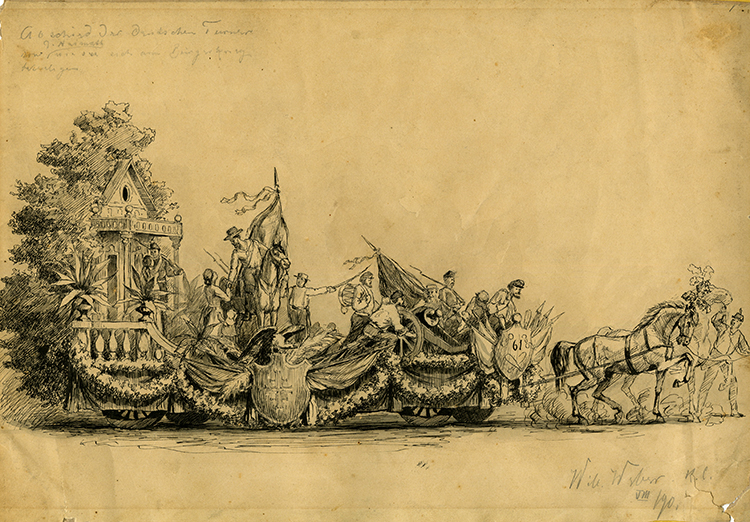

BY STEPHANIE HATFIELD

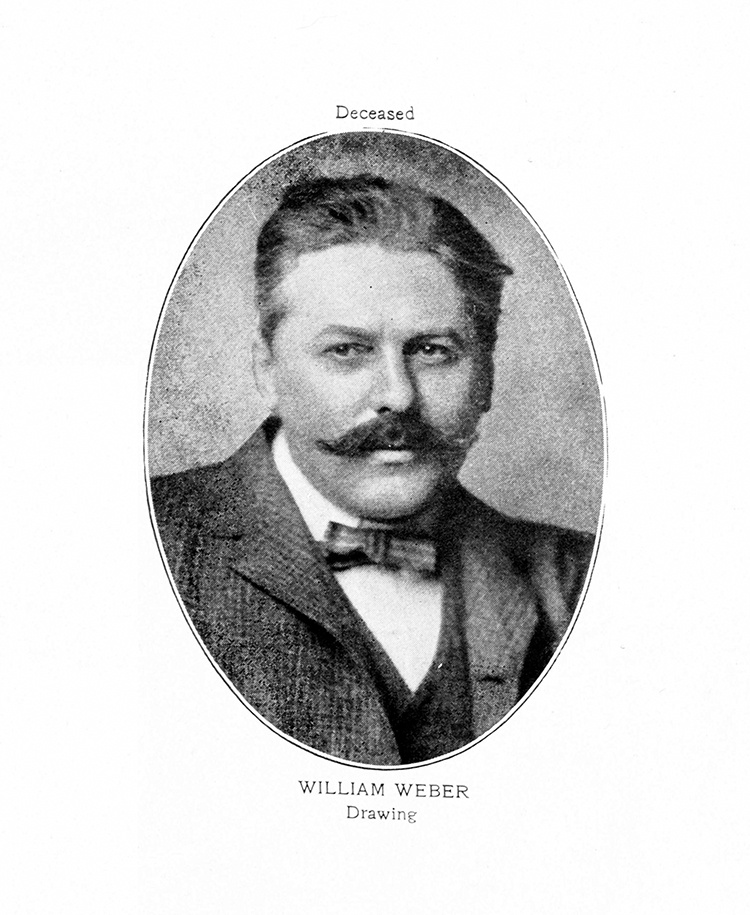

The beautifully detailed ink and graphite illustration of a parade float, shown above, depicts a poignant Civil War scene. Union soldiers cling to loved ones before they set off for war. A small group of men march forward while pushing a cannon. A drummer, American eagle, flags, and shields add to the patriotic imagery. And scrawled in the bottom right corner of the illustration is a signature: Will. Weber. K.C.

The artist, German-born William Weber, is the subject of our first “Art in the Archives” installment. His Civil War float may have been designed for either the Priests of Pallas or German Day parades of the early 1890s, which both took place in October and featured similar themes from history. As we will discover, Weber’s parade float designs are only a small part of his artistic legacy.

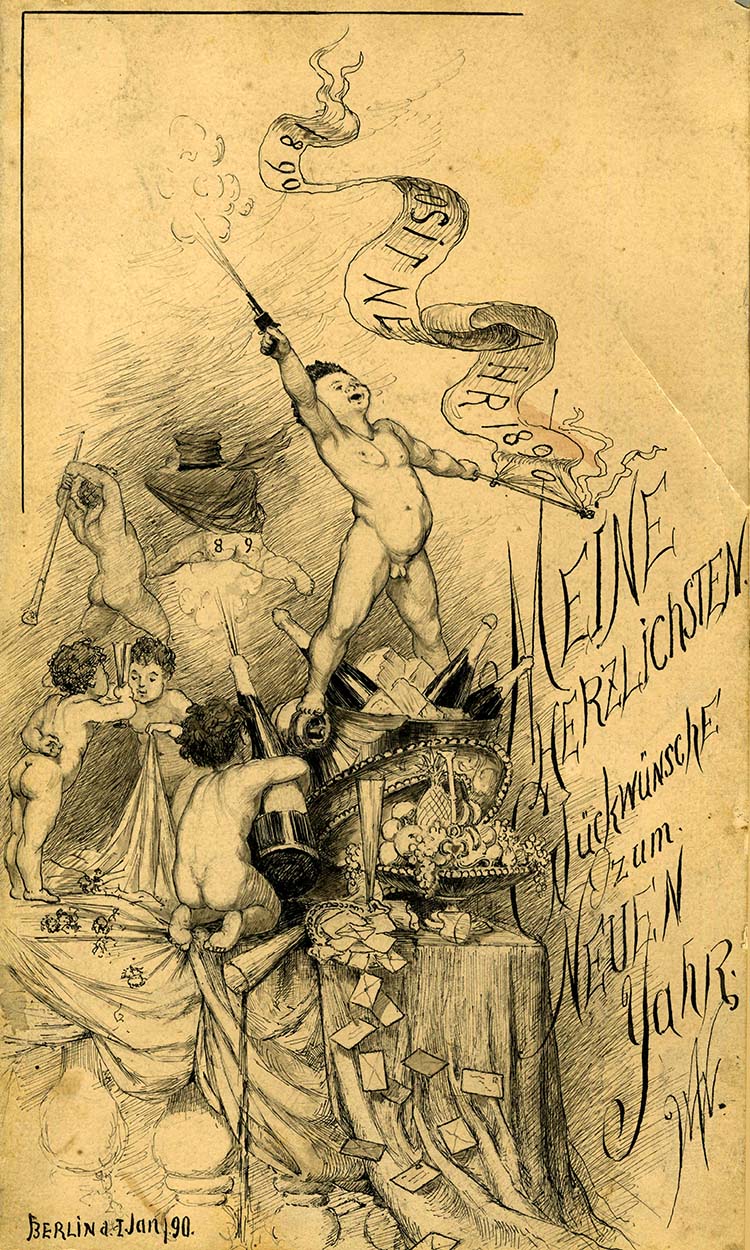

William Weber was born in Gross Geran, Germany, on July 10, 1865. Though his family moved to America when Weber was quite young, he migrated back to Berlin when he was 19 or 20 for six years of art study and travel across Italy, Belgium, and Holland. He returned to the U.S. in 1890 and opened a studio in Kansas City. His first commission was to design parade floats for German Day, a festival celebrating German immigrants.

By all accounts, Weber was a stunningly detailed artist and dedicated art instructor. He held teaching positions at a variety of institutions – first employed at Fenton’s University for Boys in Kansas City, where he taught night classes out of a local YMCA building, and later at Central High School in Kansas City. Centralian yearbooks from the early 1900s mention his positive effect on the art department. It was said of Weber in the 1900 annual: “[He] is so well known in this city, that it is almost unnecessary for the Luminary to speak of him.”

A former student of Weber, Maud Hastings, wrote an article about him in the April 1897 issue of The New Race. She explained how she went to Weber for lessons while visiting Kansas City. Surprisingly, he did not encourage her interest in art, and as such, she left. Only after wasting time and money at another studio did Hastings realize that Weber dissuaded her due to her lack of earnest interest in becoming an artist. She praised his sincerity to both the advancement of art and his dedication to teaching for the sake of education.

Weber died of typhoid fever in 1905 at age 39. Central High School closed for his funeral so his students could attend.

His obituary in The Kansas City Star noted that the funeral was one of largest ever attended in the city, which spoke to Weber’s influence in the community and on his students. It went on to say: “Mr. Weber was a genial and companionable gentleman. He made friends and never enemies. He was intensely devoted to his profession.”

Weber’s work may not be housed in the Nelson Atkins Museum. His name may not be as well known to locals as Thomas Hart Benton or George Caleb Bingham. However, one of his students, Bessie Wolf, in her commemorative of him, sums the effect of the artist on the world:

“When once laid to eternal rest, it is only a matter of time before the departed is forgotten. The artist, however, is an exception to this rule, for all his beautiful thoughts – in fact, the best part of his mortal self – are reproduced by him on canvas. And as Time is unable to efface a great painter from the memory of the public, so age cannot destroy his handiwork. … Truly may we say of this well-esteemed man, ‘Gone, but not forgotten.’”