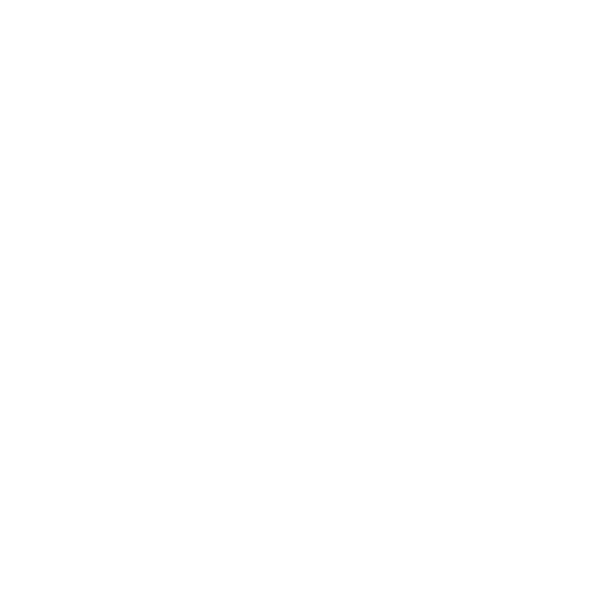

She was KC’s ground-breaking librarian. Then she was told her job was ‘for a man’

With the Kansas City Public Library celebrating its 150th anniversary, staff have spent the year thinking about and promoting our history. One KCQ reader who recently visited the Central Library in downtown Kansas City noticed handouts about KCPL's first librarian and asked us who she was.

Carrie E. Westlake was born on a Virginia plantation in 1851. That same year, her father Wellington was awarded land in Winfield, Iowa, for his services in the U.S. Army. The family made the 600-mile journey west in a canvas-covered wagon, where upon arrival, they built a stock farm.

The Westlakes led a simple life in the rural plains. Carrie's mother Hellen instilled the customs of Southern tradition. She was to become a "proper young lady," limited to a life of domestic duties in preparation for marriage. But it was while receiving an education at a nearby schoolhouse that Carrie found her true calling: A love of learning.

At age 18, Carrie left the countryside for the bustling city of St. Louis, Missouri. In her 1908 book, "Kansas City, Missouri: Its History and Its People," she suggests that she stayed with relatives while attending private school. It was around this time that she met Edward Judson, a student at the St. Louis Physicians College, and on June 1, 1875, they were married.

The couple moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Edward set up practice. Their union didn't last long, however, as Carrie discovered Edward had been unfaithful to her after contracting a venereal disease from him. In October 1879, Carrie, alone and pregnant, traveled to her parents' new home in Sedalia to give birth to her only child, Edith Westlake Judson. Moments later, the infant died of an "imperfect heart."

From that day forward, Carrie declared that she was no longer Edward's wife. She entered the Jackson County Courthouse in Independence and "prayed for a divorce." While awaiting the verdict, she relocated to Kansas City and took up work as a bookkeeper. Fortunately for Carrie's future career, her landlord was Dr. James Greenwood, superintendent of the city's public schools. Impressed by Carrie's keen intelligence and drive to learn, he offered her a position as the district's first librarian.

On March 16, 1881, she was hired at $30 per month with the stipulation that she was to meet the school board's rigorous demands — the library was to operate as a sphere of "intelligence and information for the entire city," and it was her duty to instill within the city's children "a correct taste for reading the best authors."

With 3,000 works under her stewardship, Carrie organized the first catalog and transformed three rooms in the Board of Education building into a public library. Shortly after, she received the news she'd been waiting for — her husband was found guilty of adultery and their marriage was dissolved. She was in the position to put the past behind her and live a life that aligned with her ambitious spirit.

Carrie later married James Steele Whitney, a writer for "The Kansas City Star." Their relationship ended when James died of tuberculosis in 1889.

Carrie's accomplishments during her 30-year career left an indelible mark on library history. In 1888, she established the first reference room for children in the United States and in 1900, she was among the founding members of the Missouri Library Association. Her contemporaries traveled long distances to learn about public librarianship, and she gave speeches that drew praise including: "Libraries and Reading Rooms as Intellectual Environments" and "The Advantages of the Library to the Technical Man."

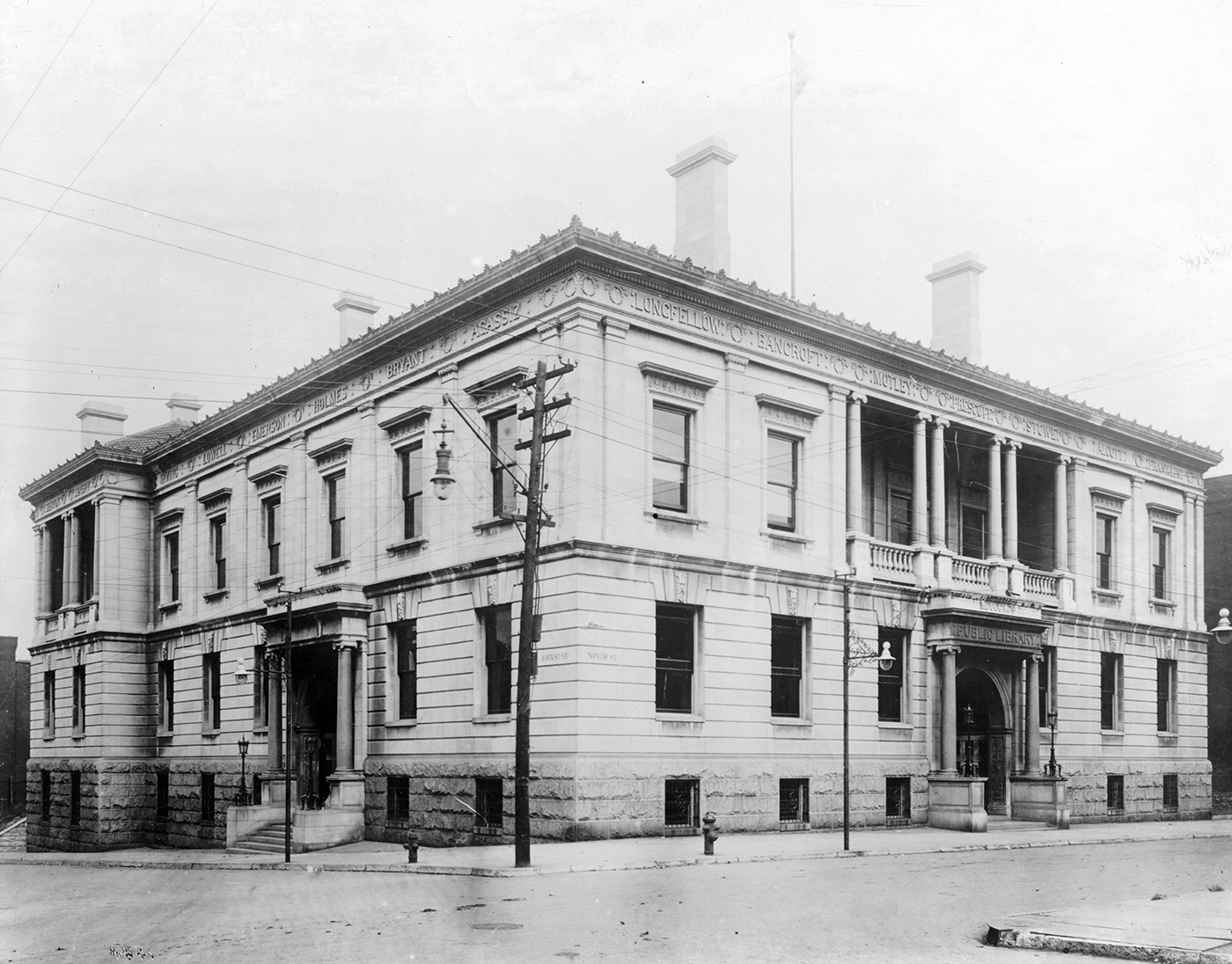

The construction of the city's first purpose-built public library building at Ninth and Locust streets in 1897 was accelerated by Carrie's push for "more space, and more books!" The structure still stands today and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

At the 1898 American Library Association (ALA) conference, a librarian who had visited the Kansas City Public Library, called it the "most complete and up to date library in the United States," and credited "one little woman and her big ideas, Carrie Westlake Whitney." From 1901-1910, she wrote 40 booklets titled "The Library Quarterly," which offered educational tidbits, reference materials, and book recommendations. These guides substantially influenced the collecting decisions of American libraries at the time.

Over the years, Carrie earned the moniker, "The Mother of the Kansas City Public Library." Her favorite hobby was "saving boys" by teaching them to read, and her dedication to educate all classes of people can be summoned up by her motto, "We can always find someone whom we can help and thus soften our own sorrow."

Although many of the library's early successes were due to Carrie's efforts, many of the day-to-day operations were handled by her assistant and partner of over 40 years.

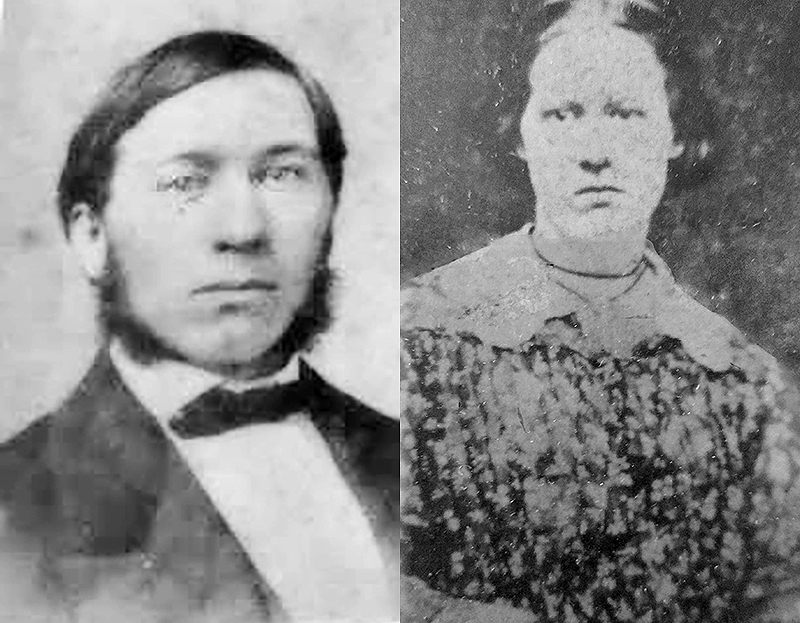

Born in 1861, Frances "Fannie" Bischoff grew up in the city of Evansville, Iowa. She was the fourth child of seven and the only daughter to parents Emil and Francesca. The profits from Emil's German newspaper business allowed the family to live very comfortably. After Emil's death in 1877, the family changed their name to Bishop and brothers Theo and Arthur created a joint venture called Bishop Bros. Printing in Kansas City.

On Oct.28, 1886, Fannie rode the train to Union Station and settled into the house catty-corner from Carrie's. Two years later, they were living together at 1455 Harrison St., a short distance from the Chase School where Fannie was a teacher. Three years later, she was hired as head cataloger at the library and was promoted to assistant in 1895.

Despite her positive influence on libraries, Carrie had shortcomings. She fought with teachers after sending students back to school without their required books because she found their reading lists "unsuitable" for children. She also found herself at odds with the public she served. Her decades-long campaign to eradicate the "national taste for reading trashy literature" was well received early in her career, but as the city evolved, so did its reading interests.

The School Board noticed these conflicts and Library Committee member Frank A. Faxon made changes to undermine Carrie, including hiring attendants without her consent and allowing them to disobey her. One new attendant even spat in Carrie's face when she reminded her to follow library procedures! Carrie asked that the attendant be punished, but no action was taken by the board.

Following Carrie's return from the 1910 ALA conference, she was served notice that "…the board of education decided that the public librarian was for a man, one of college library training." Patrons, suffragettes, and teachers came to her aid, demanding that she be retained. Under intense pressure, Faxon chose instead to demote Carrie and Fannie to assistants for the new librarian.

There was internal strife when Purd Wright, former head of the St. Joseph Library, was hired to replace Carrie. Library staff disagreed on who was in charge, including Carrie herself. Unable to maintain order, Purd left temporarily due to "ill health." The board found Carrie at fault for the confusion and fired her on Sept. 6, 1912. Fannie was sent away to manage the Swope Settlement Library until her retirement in 1914. Both women stayed by each other's side until Carrie's passing on April 8, 1934, at age 83.

Defying the expectations assigned to her gender, Carrie Westlake Whitney was named KCPL's first librarian when the profession was still dominated by men. She used her position to expand the public's access to knowledge and her teachings were instrumental in advancing the field of librarianship.

From her obituary: "After her retirement Mrs. Whitney lived a very quiet life. She and Miss Bishop, bound by a rare and beautiful friendship, found happiness in each other and the books with which they surrounded themselves. They dropped out of the great current, but they never lost interest in its movement and its ever-changing character."

As the Kansas City Public Library continues to celebrate "150 years of discovery" throughout 2024, it is important to remember that our first librarian, despite imperfections and an unjust dismissal, set the organization on the path to becoming a doorway to knowledge for all Kansas Citians.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.