Once a star of the Kansas City skyline, this 90-foot cow statue now sits alone in park

Readers who have walked the Riverfront Heritage Trail sometimes write in to ask about some of Kansas City’s more obscure public art pieces, such as West Pennway’s miniature Mayan pyramid or the I-670 pedestrian bridge’s iron birds. One piece, however, stands above the rest as an object of reader intrigue: the Hereford Bull atop a pillar in Mulkey Square Park.

For over 20 years this massive bull has stood guard by the old FBI Kansas City Field Office at 14th and Summit. But the statue has a longer history. It was an iconic feature of Kansas City’s skyline long before ground was broken on the FBI building and, indeed, even before I-670 and I-35 carved Mulkey Square into the island it is today.

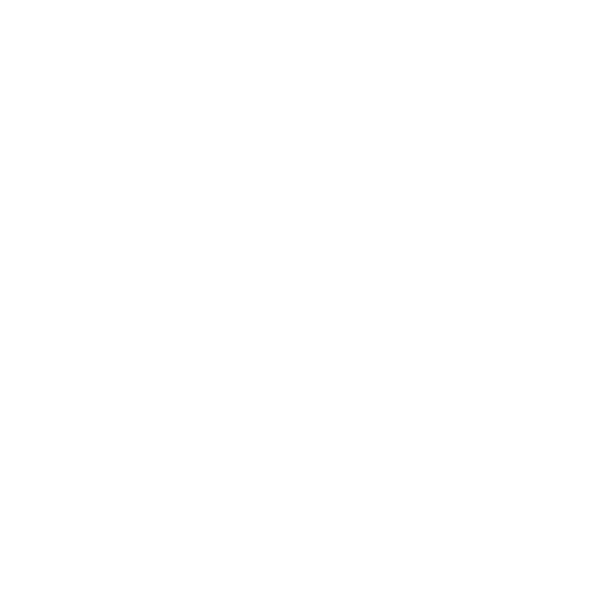

The mighty Hereford first adorned the horizon in 1954, fewer than 800 feet to the northeast of his present position. He was conceived as the capstone to the new headquarters of the American Hereford Association (AHA), a million-dollar project announced in early 1951, four blocks west and three times larger than its previous headquarters at 300 W. 11th Street.

The expansion was long overdue.

Between 1920 and 1950, annual registrations of Herefords had more than quadrupled, totaling 5.5 million new cattle over 30 years. Tasked with maintaining these pedigrees, the AHA had likewise exploded from 15 to 135 employees.

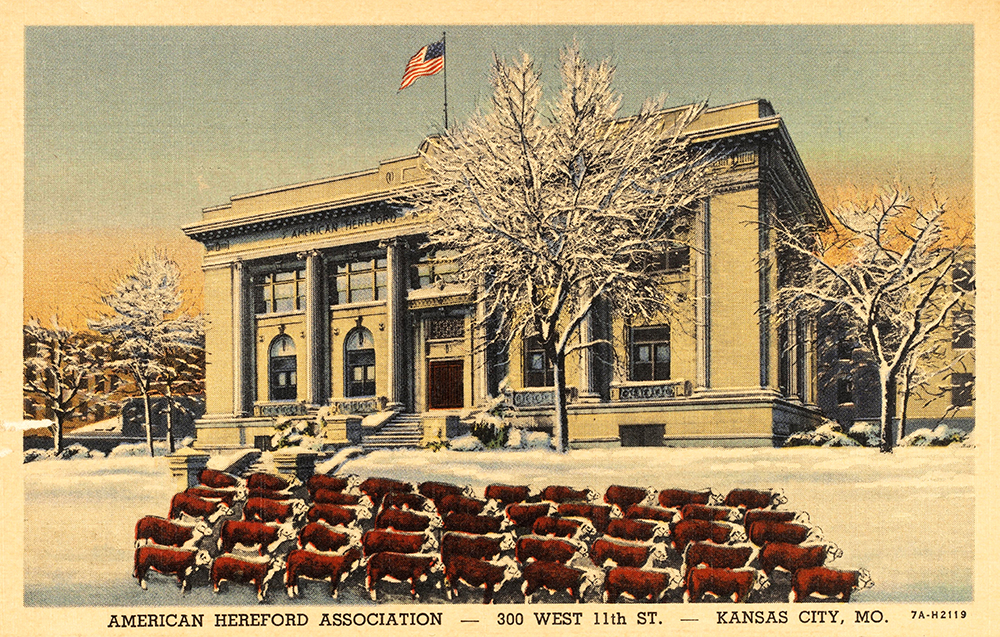

A site for the new headquarters was selected atop a high bluff at 11th and Jefferson streets with a commanding view of the West Bottoms. The building’s design was taken on by renowned Kansas architect Joseph Radotinsky, himself a Hereford farmer, who envisioned the statue as integral to the building.

Early renderings accentuate the statue but also contain a slight discrepancy — the bull’s direction. In some renderings he faces west, overlooking the railyards, while others have him facing south, maximizing his visibility from the Stockyards. This discrepancy would not be resolved for several years, but in the moment, crafting the statue itself posed significant challenges.

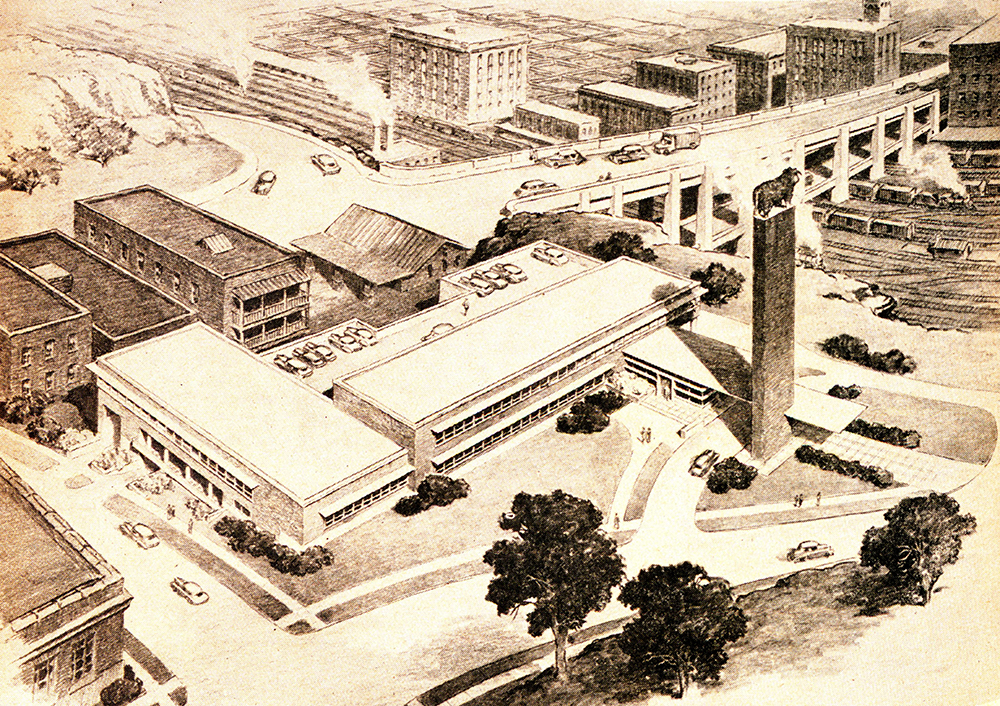

Around the time the new headquarters plan was announced, AHA field man Bud Snidow accompanied a team of sculptors from the firm of Rochette and Parzini to a farm in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland, to visit a very special Hereford.

Hillcrest Larry IV, a three-year-old, 1,900-pound bull who had just sold at auction for a record-breaking $70,500, stood as a testament to the profitability of the Hereford breed and made an auspicious model for the AHA’s totem.

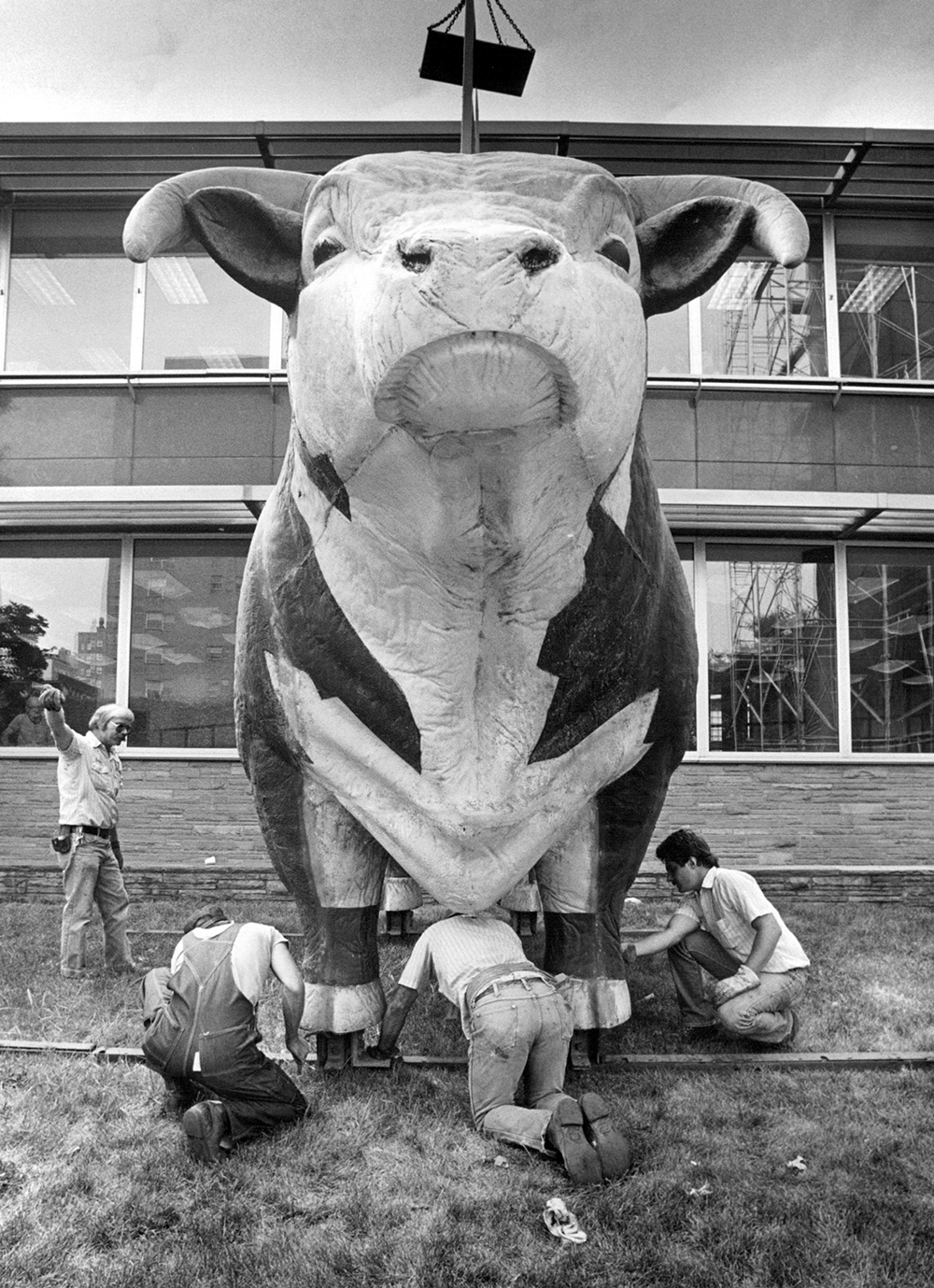

Radotinsky passed the photographs, measurements, and miniature model of Larry to the Colonial Neon Company, a New Jersey manufacturer of advertising signs that agreed to build the bull after two competitors deemed the project impossible. Those doubts were not unwarranted.

The statue would consist of 39 sections of molded fiberglass-reinforced polyester plastic surrounding a steel frame. Not only did the statue need to resemble a real-life Hereford, but it also needed to withstand rain, hail, 110 miles-per-hour winds, and temperatures from -40 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Finally, like all good advertising signs, it needed to glow. This last feat was accomplished with over 700 linear feet of high-intensity cold cathode tubing.

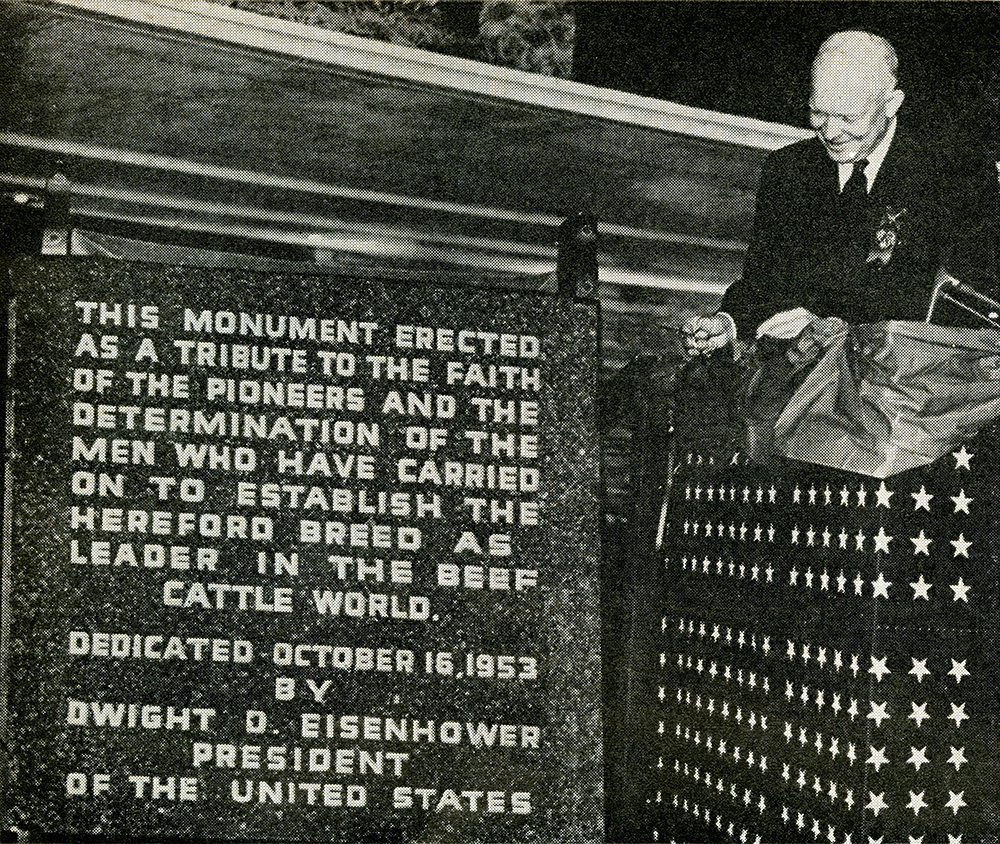

Unsurprisingly, the fabrication of a 5,500-pound three-times-life-size bull using relatively new materials took longer than expected, and by summer 1953, the bull was only half finished. The timing was unfortunate. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had already accepted an invitation to Kansas City that October to participate in the American Royal and dedicate the also incomplete AHA headquarters.

It was not until October 1954 that the completed statue made the five-and-a-half-day trip from North Bergen, New Jersey, to Kansas City atop a lowboy trailer. On October 12 he was towed out of storage to AHA headquarters and hooked up to a crane, ready to be hoisted.

The only thing left to do was decide which direction he would face, a question which, up to that moment, the group was still debating. The 90-foot rectangular pylon had been built with a north-south orientation, making a westward view impossible. And so, like many difficult decisions, it was put to a coin-toss.

AHA Secretary Jack Turner flipped a nickel, which came up heads. Two men each bearing a 10-gallon hat approached. The hats read “head” and “tail,” and from the former Turner drew a slip of paper reading “north.” The bull was thus given a commanding view of the Missouri River and the Municipal Airport.

The AHA building was officially opened later that week with a ceremony featuring a video message from President Eisenhower followed by the first public lighting of the bull.

Over the following decades the statue came to embody Kansas City’s “Cowtown” image, making him a point of pride for some and embarrassment for others. For the latter group, the statue was little more than a kitschy blemish on the skyline. Calvin Trillin, the Kansas City-born journalist, took it upon himself to defend the bull against such attacks in the pages of “The New Yorker.” Trillin’s impassioned defenses, though, could not stem the AHA’s slow decline.

By 1984, the organization no longer required such a large space, and soon left the building — and bull —behind. DST Systems, the new tenants of 715 Hereford Drive, vowed that they saw no reason to move the bull. The truth, though, was that he had already largely slipped from public consciousness.

After Mid-Continent International — later Kansas City International — replaced the Municipal Airport as the region’s primary air hub in 1972, the bull fell from the view of the passengers and pilots who had nicknamed him “El Toro.” In 1994, Bartle Hall’s “Sky Stations,” the city’s most imposing pylon-based art piece, further eclipsed him.

The final blow came in 1999 when HNTB Corporation, the old headquarters’ new tenant, announced plans for a vast remodel of the structure. The national design firm’s vision for their new headquarters did not include a 5,500-pound plastic Hereford.

For all the fanfare that attended his arrival, news of the statue’s looming descension made few waves — excepting, of course, “The indefatigable Trillin in the pages of “The New Yorker.” When the bull was finally dethroned and placed in cave storage in late 2000, The Star made no mention.

The statue’s hibernation was brief. In late 2002, he was placed upon a newly built pylon in Mulkey Square Park, the result of a collaboration between the AHA, KC Parks and Recreation, and MC Real Estate Services. His new post is undoubtedly of less prominence and visibility than his last, but his view still includes the Municipal Airport and the Missouri River, as well as the pylon that supported him for over 45 years.

This month marks the bull’s 70th year in Kansas City. The FBI offices to his south have been vacated, so he stands alone on his forested summit. He no longer glows at night, and the surrounding trees now shield him from southbound I-35 traffic. But visitors to Mulkey Square Park might consider taking a moment to stop and marvel at Kansas City’s storied bull and wishing him well on his platinum jubilee.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.