How long has Kansas City had a Mayor’s Christmas Tree?

Each year, the Mayor’s Christmas Tree is displayed at Crown Center through the holiday shopping season. Its arrival, sometimes as early as November 3, is a harbinger of the season.

A new resident and What’s Your KCQ? reader asked how long the city has had this municipal tradition.

Its roots can be traced to the 1870s when the city was still young and hoping new rail connections could help shed its river town image and set it up as a vital connection between western livestock ranchers and eastern markets.

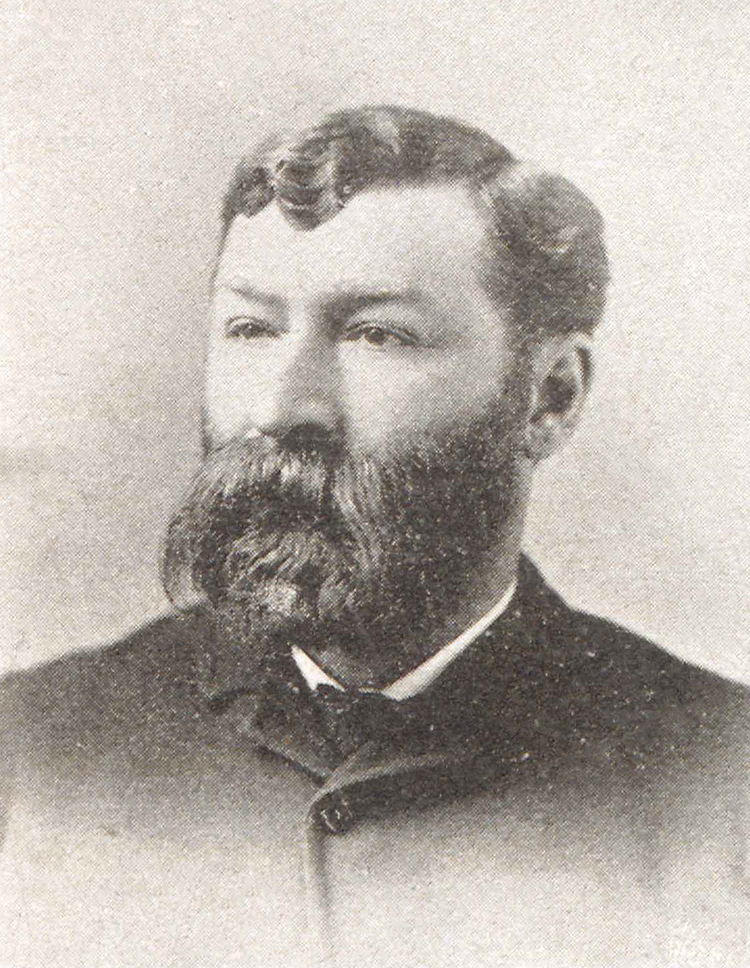

At the time, the city’s mayor oversaw administering aid to less fortunate citizens, a duty that Mayor George M. Shelley apparently took seriously. Despite the city’s rapid growth in the 1870s, the winter of 1878 was reported to have been particularly hard on some of its citizens.

Reminiscing in 1925, Shelley said of them, “Many of these persons, especially the jobless, would have no Christmas, I knew, unless the mayor made one possible for them.”

Anyone in need could request provisions for a Christmas dinner from the mayor’s office. At his own expense, Shelley purchased enough groceries to fill about a thousand baskets. He also purchased 50 cords of firewood and had them stacked in Market Square (today’s City Market) for all who needed it.

Those who arrived at City Hall to pick up their baskets would have seen a rather modest tree – with very little pizzazz.

According to a 1929 story in the Kansas City Star, German immigrant Oswald Karl Lux created the first illuminated Christmas tree in the area in 1882.

Unable to locate an evergreen tree of the appropriate size to light and decorate with candy and toys but wanting to share the German tradition he’d grown up with, he took matters into his own hands. Lux, a cabinet maker, fashioned a sturdy tree using a broomstick for the trunk and whittled down barrel slats for branches. He attached evergreen sprigs collected from Union Cemetery and candles to the branches.

Lux’s family tree was a hit in Westport where his family lived, and a few years later, possibly due to that popularity, shipments of trees from Michigan arrived in Kansas City for others to decorate in a similar fashion.

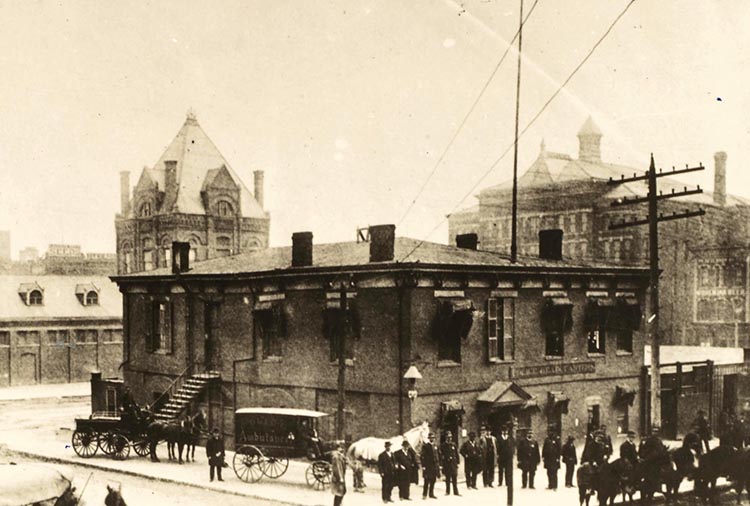

Shelley repeated his act of charity the following Christmas with a party held at Turner Hall at 10th and Main during which he played the part of Santa Claus to entertain the children.

The following year, Charles A. Chace was elected mayor and ceased the Christmas baskets and party. He may have had valid reasons for doing so, but without knowing them, it’s easy to remember him as a Scrooge.

The possible Scrooging continued through several administrations.

Finally, in 1908, Thomas T. Crittenden Jr. restored Christmas giving to the mayor’s office. Mayor Crittenden had been on the planning committee for the Fraternal Order of Eagle’s annual children’s Christmas party and wanted to do something similar on a city-wide scale.

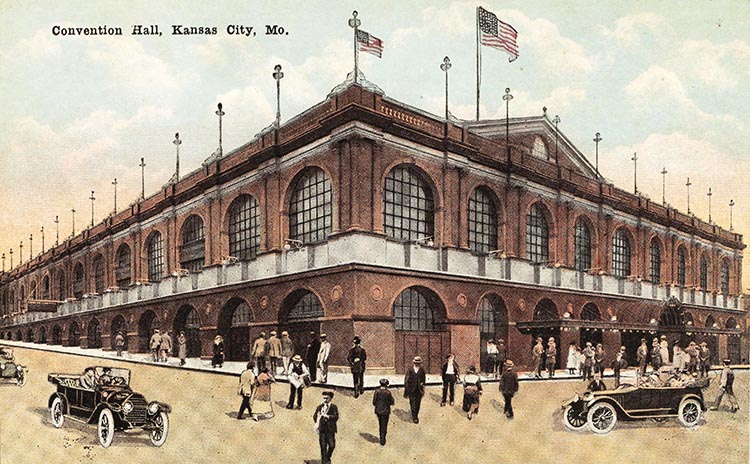

Crittenden created the Mayor’s Christmas Tree Fund and solicited donations from the public to pay for a Christmas party and tree. The first campaign raised about $10,000. On Christmas morning, children arrived at Convention Hall and were greeted by “the largest tree that was obtainable … surrounded with baskets of provisions for needy families and with heaps of candy and toys for children.”

The revived party wasn’t without its problems. The crowd huddled outside waiting for Convention Hall to open on Christmas morning was much larger than expected. Word had gotten out and children from surrounding areas flocked into the city to attend.

Some attendees removed or hid the stamp on their hands so that they could take more than one basket. Others requested extra baskets for siblings who couldn’t attend. In the end, about two thousand children went home empty handed. To make amends, the disappointed children were issued vouchers redeemable for a gift basket the following day.

Despite the trouble, Mayor Crittenden declared the party a success and assured the public it would return the following year.

And return it did.

The Mayor’s Christmas Tree Association learned from prior mistakes and made changes. When asked about the children from other cities who received gift baskets, Crittenden was ambivalent. He simply said more funds would need to be raised in the future.

The organization stayed non-partisan, and in a city whose 20th century history was defined by Democratic machine politics followed by Republican reforms, this was no small feat. Everyone worked together to ensure the party went off without a hitch year after year.

And while public life in Kansas City was racially segregated in many ways during this time, the Mayor’s Christmas Tree parties were open to “all nationalities, creeds, colors and races.”

The mayor or some other dignitary always played the part of Santa Claus. Vaudeville shows and pageants kept the children entertained in the early years. Later, motion pictures largely took their place.The parties were held at Convention Hall until 1935 when the event moved to the newly opened Municipal Auditorium.

Mayor H. Roe Bartle made a couple of significant changes during his administration. First, in 1955, he decided to direct some of the organization’s fundraising toward the city’s elderly and disabled population; it continued delivering gifts to children in need, but the parties ceased.

Bartle replaced them with the Mayor’s Christmas Tree lighting ceremony that we know today in 1957. On the evening of December 12, a crowd of about a hundred gathered at Auditorium Plaza (today’s Barney Allis Plaza) to watch Bartle illuminate a 35-foot-tall tree. Just before turning the switch, he said, “This will be Kansas City’s Christmas tree,” and declared it a symbol of love for fellow citizens and a reminder that those in need have not been forgotten.

The Bendix Coraleers, a 42-member vocal group, treated the crowd to Christmas carols. And with that, the Mayor’s Christmas Tree lighting ceremony was born.

From 1959 until 1972 Gillham Park was home to the tree. The following year, the city moved it to its current home, Crown Center, where the lighting ceremony is held each year on the Friday following Thanksgiving.

The 1973 lighting ceremony almost didn’t happen. In response to a Middle East oil embargo of the United States, President Richard Nixon called on Americans to conserve energy by curtailing holiday light displays. Mayor Charles Wheeler said the tree would remain dark. The Plaza lights were turned off three days after Thanksgiving.

However, when the Nixons announced they would preside over the lighting of the National Christmas Tree on the White House Lawn, organizers in Kansas City took that as an all-clear. The Plaza lights came back on, and Wheeler announced that the tree lighting ceremony would take place on December 14. Both displays kept limited hours that year.

The mayor traditionally flips the switch, but occasionally is given a hand. Chiefs, Royals, and Sporting KC players have shared the honor. Celebrities with Kansas City roots like Janelle Monae, Tech N9ne, Eric Stonestreet, and Rob Riggle have all taken a turn. Kevin Strickland, who in November 2021 was exonerated for a 1979 murder case that led to wrongful conviction and 42-year prison sentence, did the honors with Mayor Quinton Lucas standing by last year.

While modern forms of charitable giving have replaced the grocery and toy-filled baskets, the Mayor’s Christmas Tree Fund’s work to raise money to benefit those in need around the holidays continues.

There are many ways to give; a popular way to donate began in 1981 with the sale of an annual Christmas ornament design. Hallmark artist Sheyda Best designed the 2022 ornament which honors the 50th anniversary of the ceremony’s move to Crown Center. Purchase it online or at Crown Center beginning the night of the ceremony.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.