This Kansas City beach was a destination ... until disaster struck again and again

Finding a beach during the dog days of summer can be a challenge for landlocked Kansas Citians, given the area isn’t known for its wave-side scenery. Though the area has plenty of smaller beaches, the quest for a destination often includes long-distance travel and can decimate vacation budgets.

Reader Tyler Smith recently came across some old photos of locals wiling away long summer days at a picturesque beach, a mere 20-minute train ride from downtown. He asked “What’s Your KCQ?,” a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library, to help explain where the beach was located and what exactly happened to it.

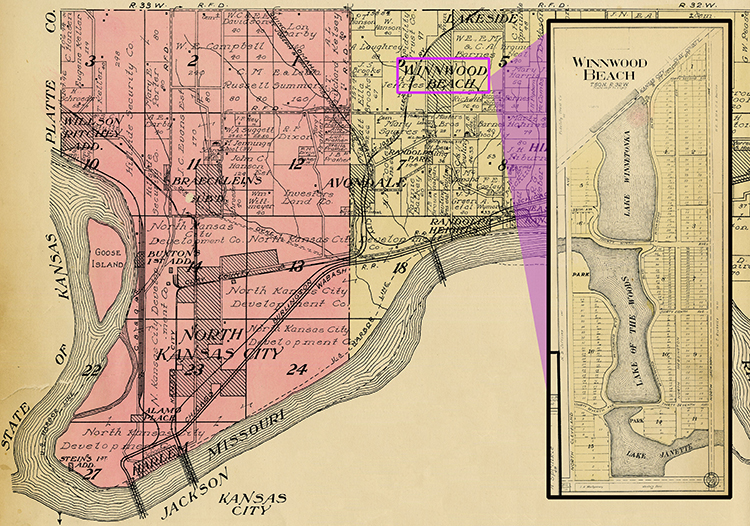

The place was Winnwood, a Clay County resort that encompassed multiple lakes and featured a variety of amusement attractions, and 300 building lots on the water. The park took its name from its founder, Frank Winn.

Winn’s family arrived in the county in 1850. He was educated at William Jewell College in Liberty, and with his father, became a successful hog farmer. Winn became known for his prize-winning Poland China hogs and seemingly could have been a success focusing solely on livestock, but the young entrepreneur had real estate on the brain.

He began planning a lake on the family property abutting the planned Kansas City, Clay County and St. Joseph Electric Railway line. The Armour-Swift-Burlington (ASB) Bridge, connecting downtown KC with Clay County to the north, was completed in 1911, and interurban trains began running to St. Joseph and back in 1913. Winn dammed a creek on the property, and the clear, spring-fed waters of Winnwood Lake were born.

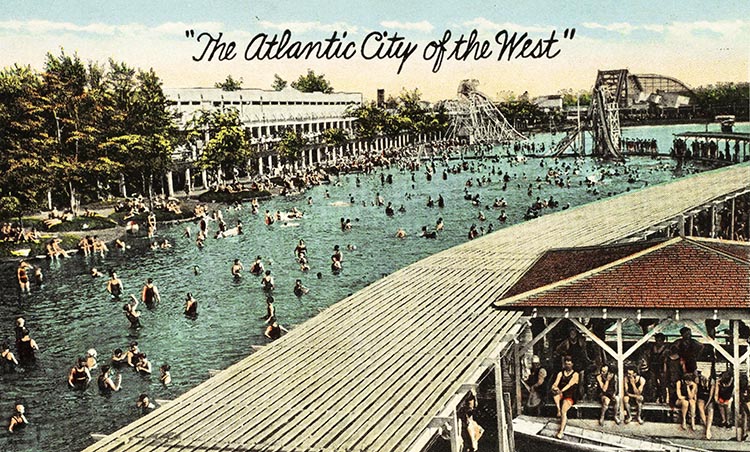

The initial plan was only to subdivide the land and sell lots to those seeking a rustic home or vacation cottage with easy access to hunting and fishing, but a 1911 trip to Atlantic City changed Winn’s mind. Back in Clay County, he created an 800-foot sandy beach along his lake’s shore. By 1913, the dance pavilion and a canoe rental house were added. Two more lakes to the south were dug: Lake of the Woods and Lake Janet, named in honor of Winn’s wife.

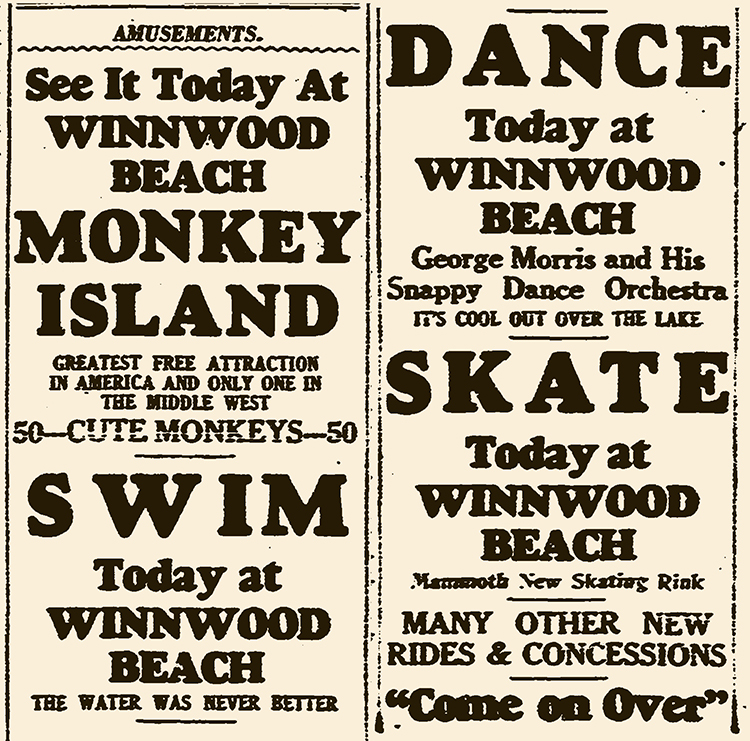

He was just getting started. Over the years, Winn added a three-story bathhouse, a diving platform, water slides, amusement park rides (including two roller coasters), a zoo, a roller skating rink and even a “monkey island.” In 1931, a group of mischievous children placed a makeshift bridge between the island and the shore, allowing 18 monkeys to escape. Two years later, an unknown trespasser released 43 monkeys from their winter quarters on the Winn farm. Both incidents required multiday efforts to track down the elusive primates.

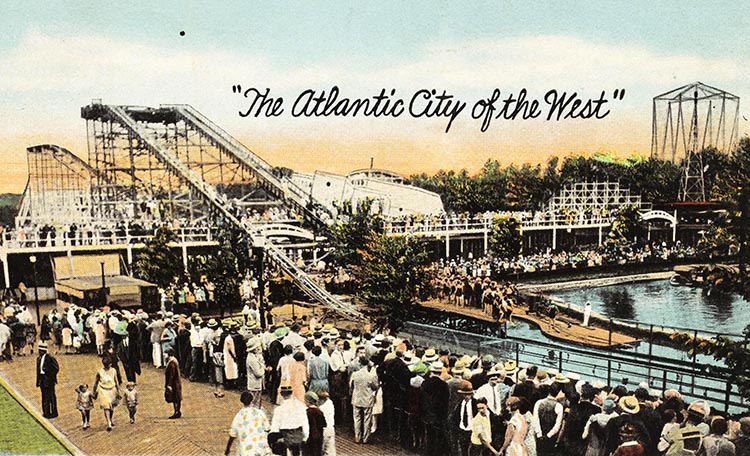

The feather in Winn’s cap, however, was a 40-foot-wide boardwalk built to mimic the one he had seen on his trip east. Winnwood Beach took on the nickname “The Atlantic City of the West.”

Once the roads were improved, buses and automobiles brought even more people to the park. At the height of its popularity in the 1920s, Winnwood Beach occupied 150 acres and saw upward of 10,000 visitors on busy Sundays. The cottages springing up around the resort were in demand and sold well.

Many making the trip couldn’t afford the rides and other entertainment, but Winn kept the picnicking and swimming free of charge. He even provided free firewood for cookouts.

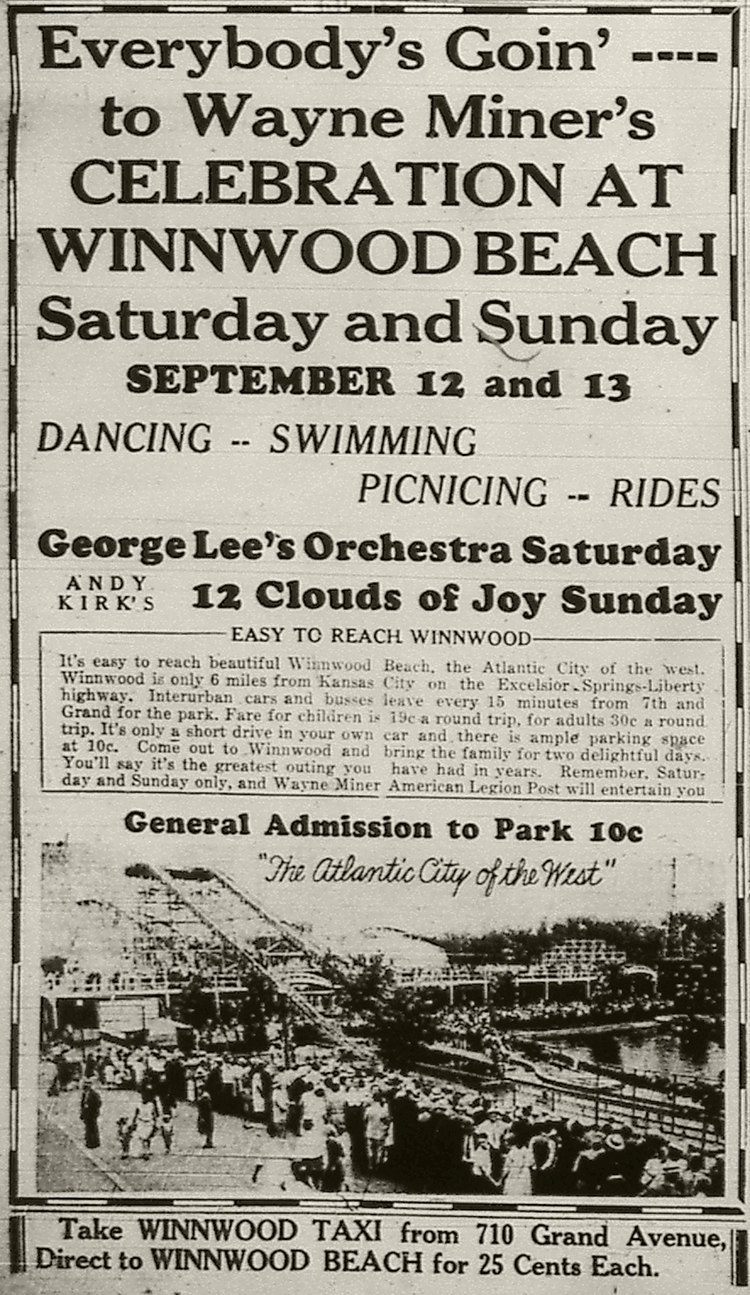

While the cost of admission was a problem for some, others were excluded as policy. Like many early-20th-century attractions, Winnwood Beach was not open to Black people. At the same time, jazz musicians and other Black entertainers were frequently hired to perform for white customers at the park.

According to Chuck Haddix, historian and curator of UMKC’s Marr Sound Archives, two exceptions were made that allowed Black people to enjoy Winnwood Beach as paying customers.

When researching his book “Kansas City Jazz: From Ragtime to Bebop—A History,” Haddix learned that the park welcomed Black visitors during two anniversary celebrations for the American Legion post named for Wayne Miner, the Black soldier from Henry County, Missouri, killed in action in France just hours before the armistice that halted fighting in World War I. Twelve thousand Black Kansas Citians attended a two-day gathering in 1931, and Frank Winn complimented the event’s organizers in the next week’s issue of “The Call.” In 1932, the event was expanded to three days.

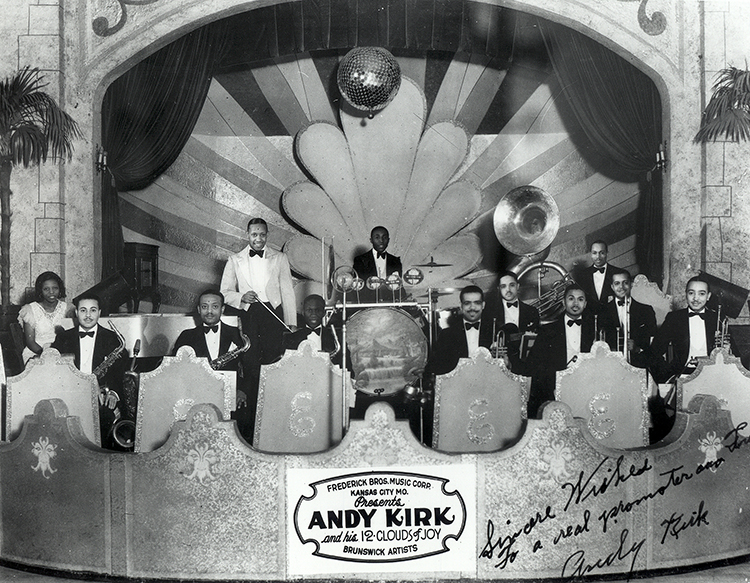

Andy Kirk and his Twelve Clouds of Joy, who played for white crowds at Winnwood Beach on a regular basis, performed for Black audiences at each of the Wayne Miner celebrations.

However, Winwood Beach’s heyday wasn’t destined to last. In what would be the first in a long string of unfortunate events, a fire from an unexplained explosion damaged the dance pavilion in 1928. The resort continued to attract visitors during the 1930s, but Great Depression took a toll on paid admission.

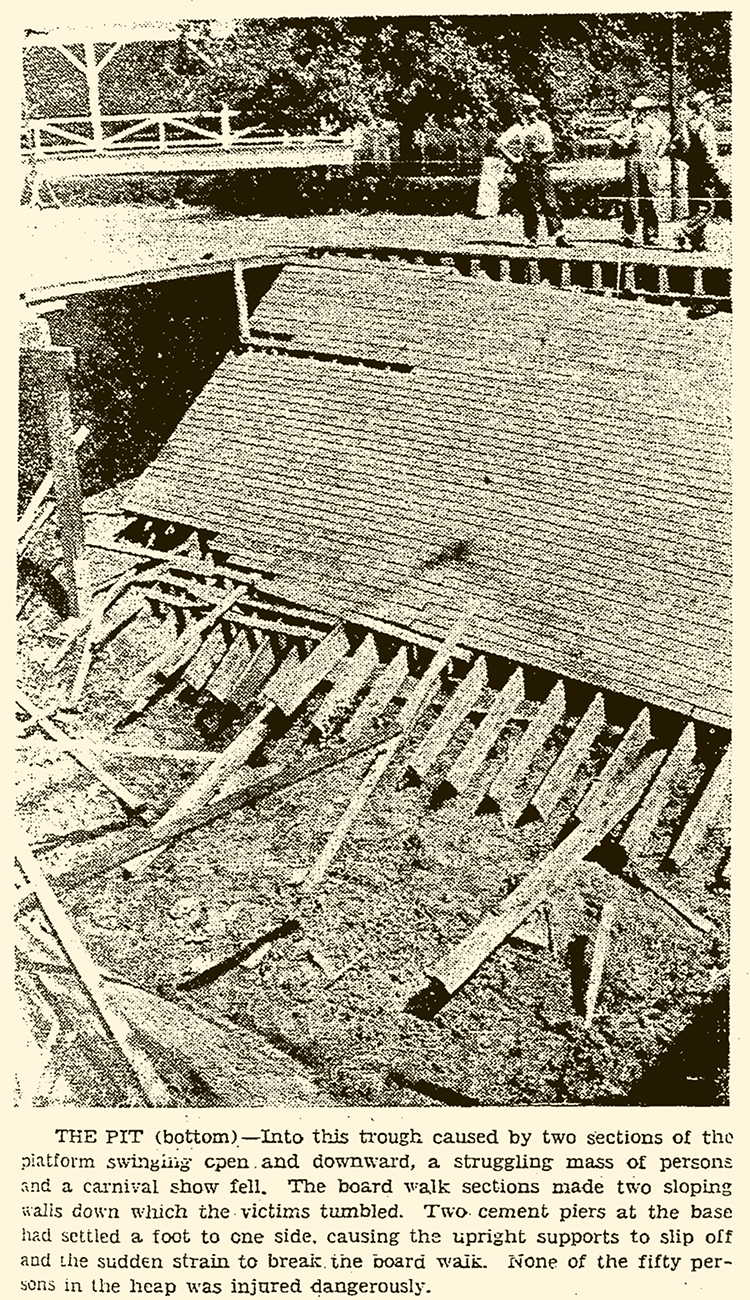

Disaster really struck during the park’s Fourth of July celebration in 1935. At around 10 p.m., without warning, a 40-foot section of the boardwalk collapsed. Around 50 visitors and performers standing near a Museum of Monstrosities exhibit tumbled 18 feet to the ground alongside the broken planks. Fortunately, the earth beneath the boardwalk was a soft, muddy mess from recent heavy rains and no life-threatening injuries were sustained.

Ambulances were dispatched but found it difficult to reach the park once the narrow roads became congested with anxious visitors hurrying to get home. The Independence Day festivities concluded with an emergency hospital being set up in the park.

Despite the accident, the park opened the following day. Repairs to the boardwalk were expedited. But it was all in vain. By fall 1935, Winn had filed for bankruptcy, closed Winnwood Beach, and withdrawn to the family home. An effort to revive the venture was made by Mary E. Winn, Frank’s sister, who bought the resort out of receivership in 1936. That June, another fire destroyed the bathhouse. In 1937, a dam burst and Lake of the Woods had to be drained. Winnwood Beach was again out of business.

Even without the once popular resort, Winnwood Lake stayed busy. In 1942, the site was purchased by a new investor who restored the beach and built a new roller skating rink. The lake continued to draw swimmers from miles around through the 1960s.

Misfortune continued to plague the site, though. Problems with its dam caused Lake Janet to be drained, the roller rink was destroyed by fire in 1966, and construction of Interstate 35 along Winnwood Lake’s northern edge filled the reservoir with silt and muddied its water.

The final blow came in 1977. The same heavy rains in September that caused Brush Creek to overflow its banks exposed critical damage to the Winnwood Lake dam. The lake was drained in 1979.

Potential investors had hopes of rebuilding a recreation center and amusement park, but the opening of Worlds of Fun made that an unlikely pipe dream. Finally, in the late 1980s, plans to redevelop the Winnwood Beach site as a shopping center were announced.

Today, few traces of the once popular attraction can be found. A small marker near the entrance to the Chouteau Crossing shopping center near I-35 and Chouteau Trafficway and Winnwood Skate Center located just to the north remind locals of Frank Winn’s dream of an “Atlantic City of the West.”

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.