Winning the home front: KC women at work during World War II

“Grandma has come out of the kitchen.”

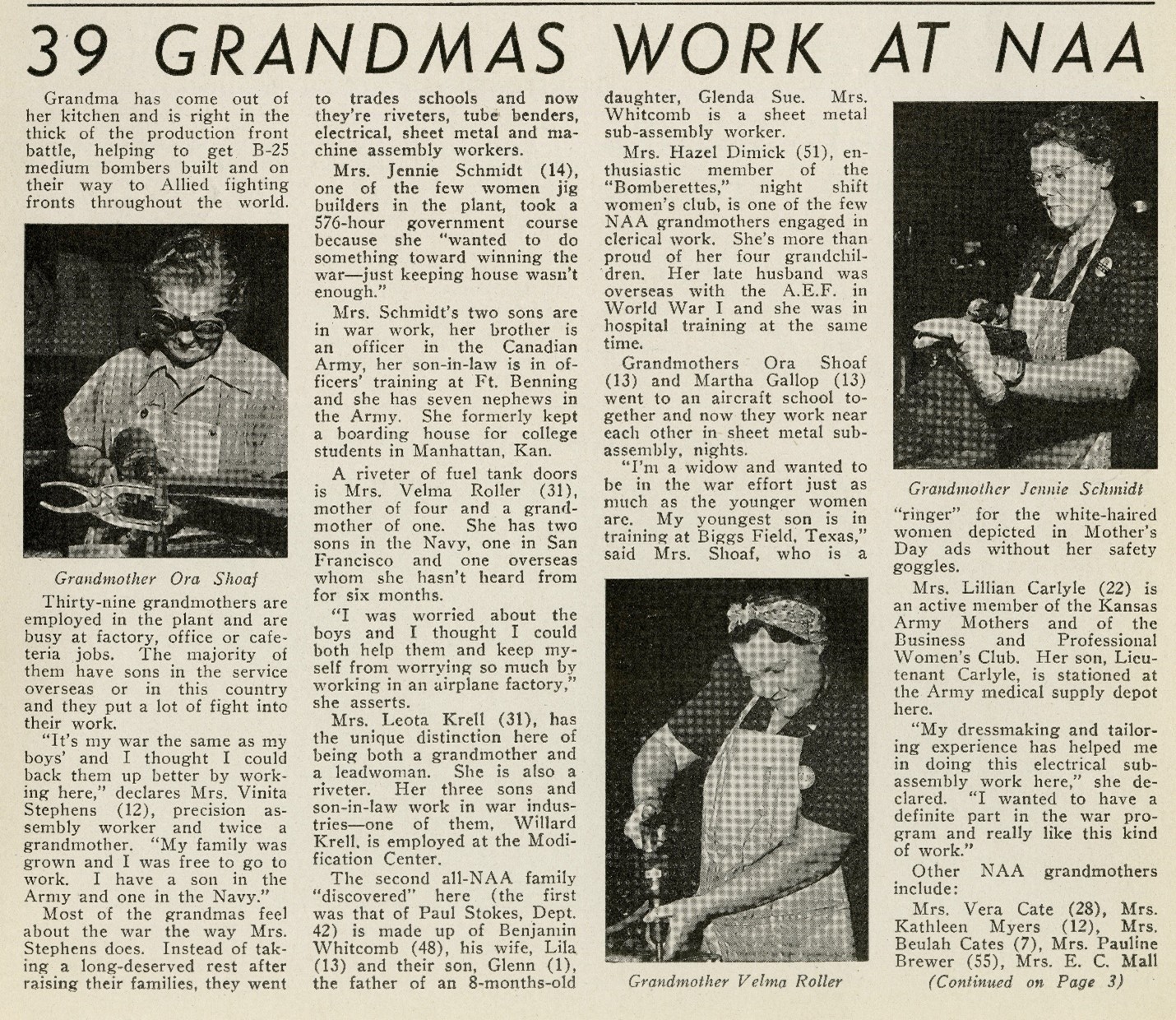

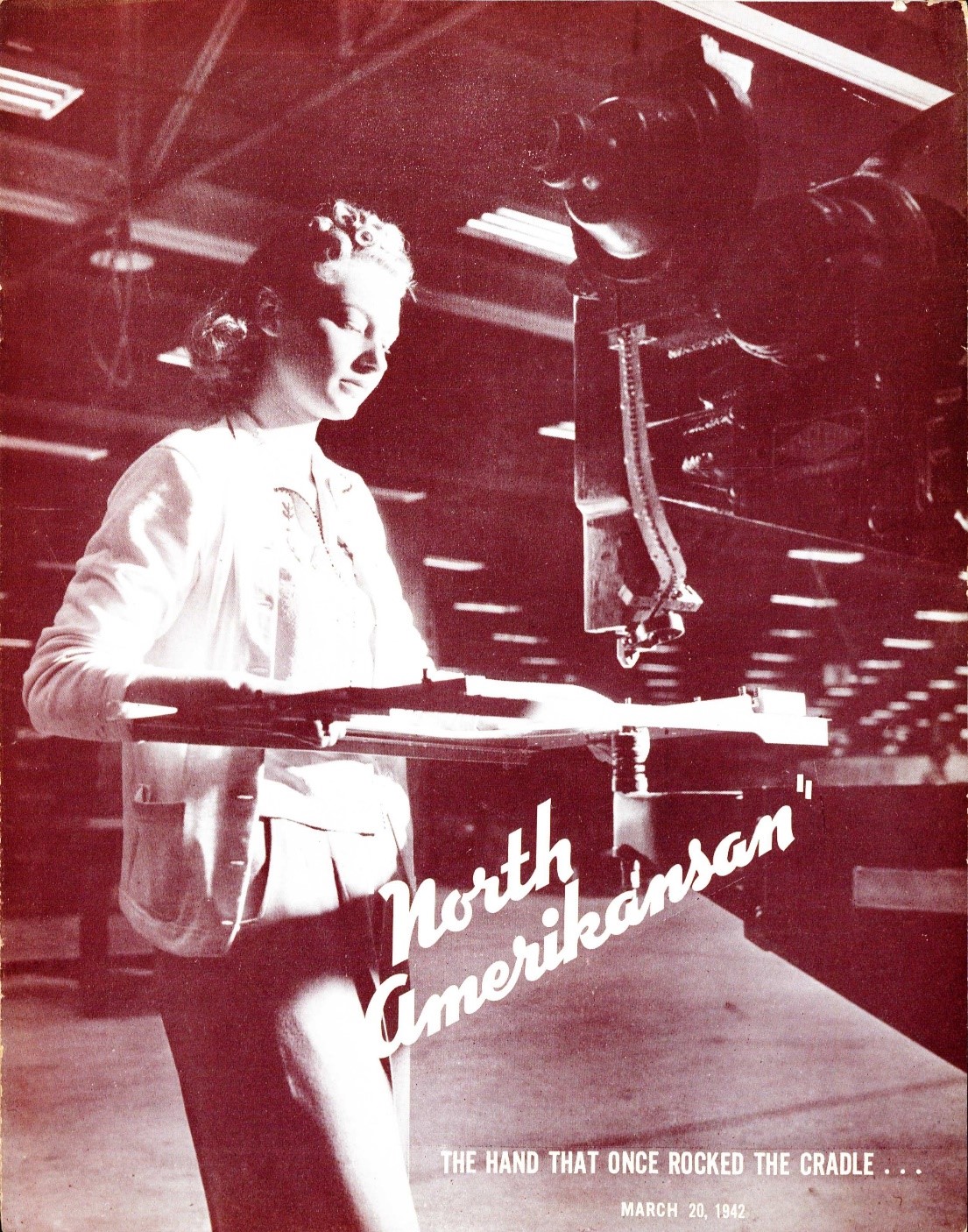

The North Ameri-Kansan, a weekly magazine from North American Aviation’s Kansas City, Kansas, plant, proudly proclaimed this in November 1942. It wasn’t just one, either. Thirty-nine women with grandchildren were known to by employed by North American Aviation at that time.

“My family was grown and I was free to go to work,” declared Vinita Stephens. With two sons in the armed forces, she decided to support their efforts by working on the assembly line.

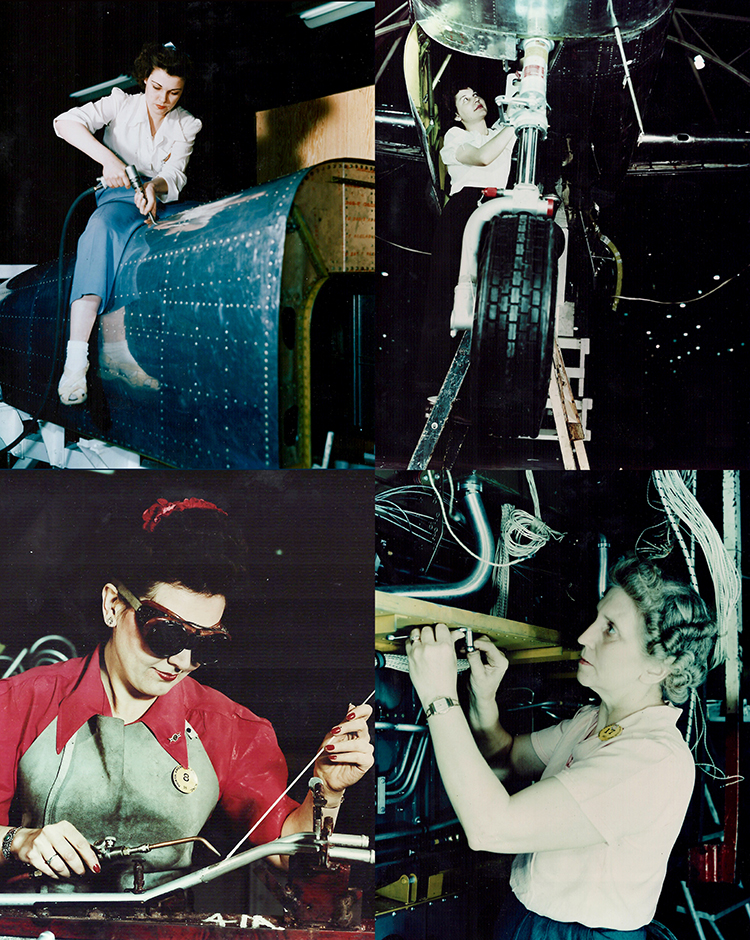

Women of all ages were entering the work force throughout the U.S. in the early 1940s as the Allied war effort ramped up. Many of them were right here in Kansas City. Some were in occupations historically thought of as women’s work, such as secretarial jobs and sewing. Others worked on assembly lines building airplanes at Pratt and Whitney and North American Aviation, or with bullets and artillery shells at the Lake City and Sunflower Ordnance plants.

North Ameri-Kansasan magazine, March 20, 1942. NORTH AMERICAN AVIATION COLLECTION (SC169)

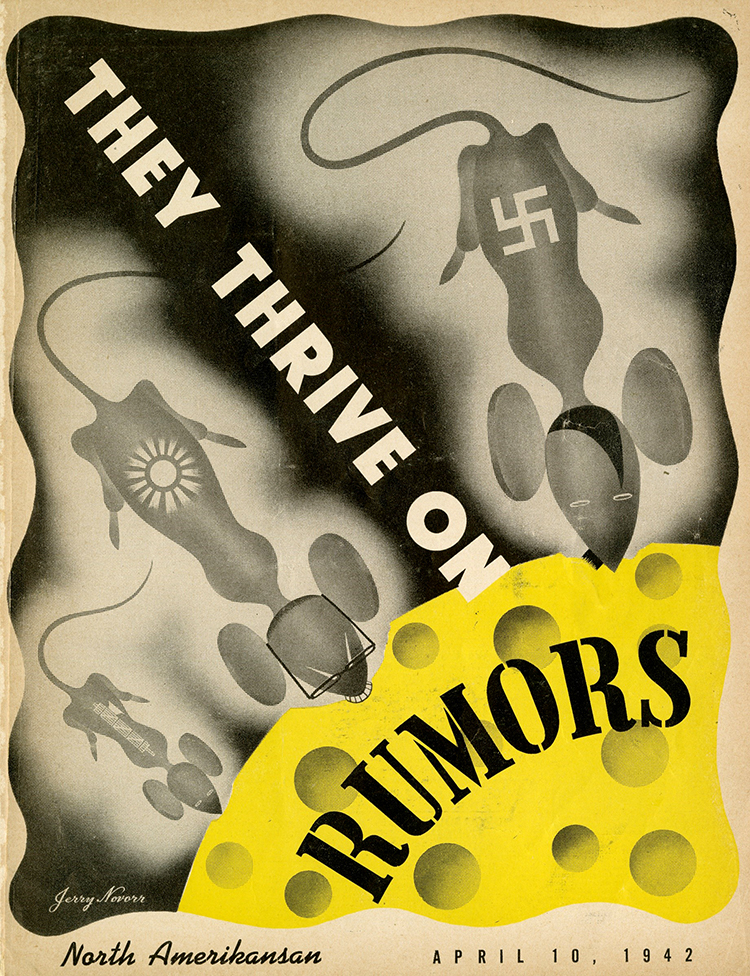

North Ameri-Kansasan magazine, March 20, 1942. NORTH AMERICAN AVIATION COLLECTION (SC169)The U.S. entered World War II in late 1941, just days after Japan’s attack on the U.S. naval fleet at Pearl Harbor. Thousands of men enlisted or were drafted into the armed services. At the same time, demand for aircraft, munitions, and other manufactured items for the war effort increased rapidly and dramatically.

Massive labor shortages were suddenly a problem. In response, manufacturers and the U.S. government began a marketing campaign aimed at women. They hoped to convince them to enter the workforce.

The ad campaign worked. Women all over the country went to work, and not just to make money or help with labor shortages. Many believed it was their patriotic duty.

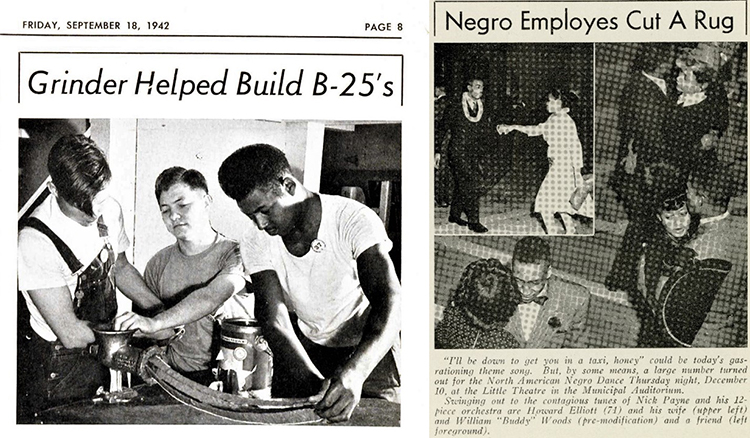

“We were very careful that every rivet was put in just right, as we realized the lives of our brave pilots and crew depended on it,” recalled Wanda Lamkins Weaver, who worked on B-25s at the North American Aviation plant in Kansas City’s Fairfax Industrial District. “It was a great honor…to help win the Great Big War” she said in Rosie the Riveter Stories: How They Did it! in 2016. “Everyone was very patriotic.”

Weaver’s story and those of dozens of other Rosies have been compiled in several books published by the American Rosie the Riveter Association.

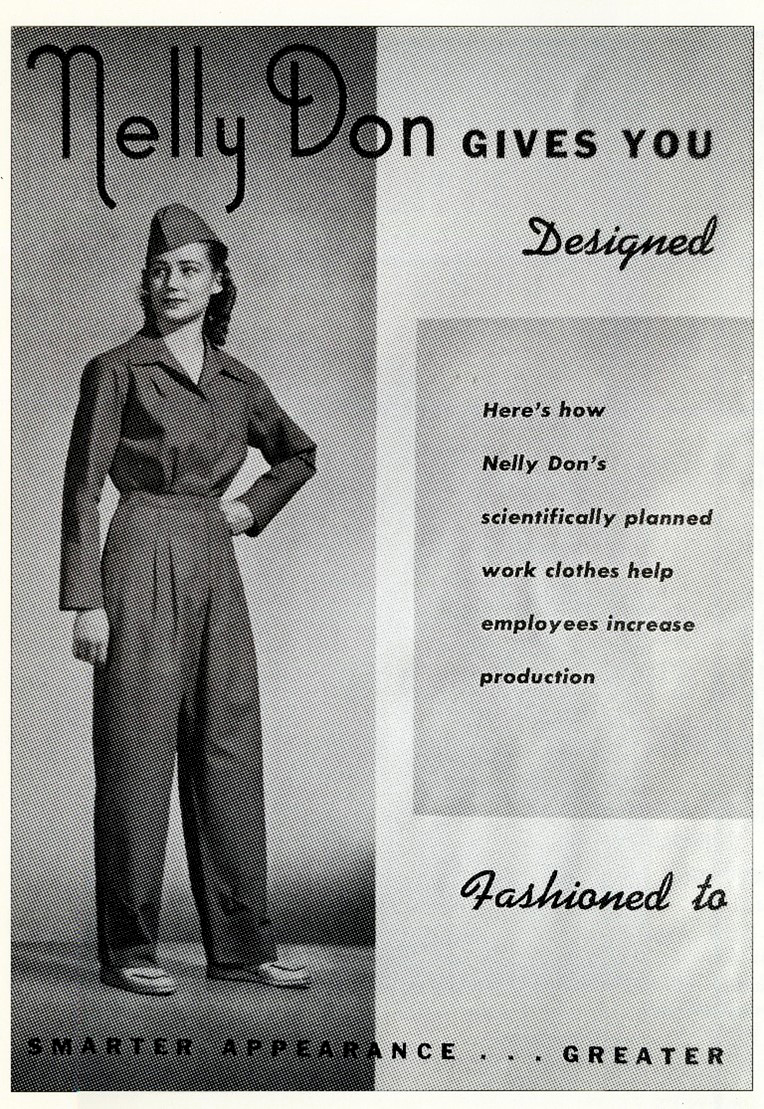

New work often required new attire. At the Nelly Don factory, women stitched together uniforms for military service personnel, and something else: pantsuits.

“Before World War II, women wore dresses,” recalled Emma Shannon Newland, a farmer’s daughter from Miami County, Kansas. As a riveter, however, she had to move in and out of airplanes as she worked. Pants were much easier to move around in.

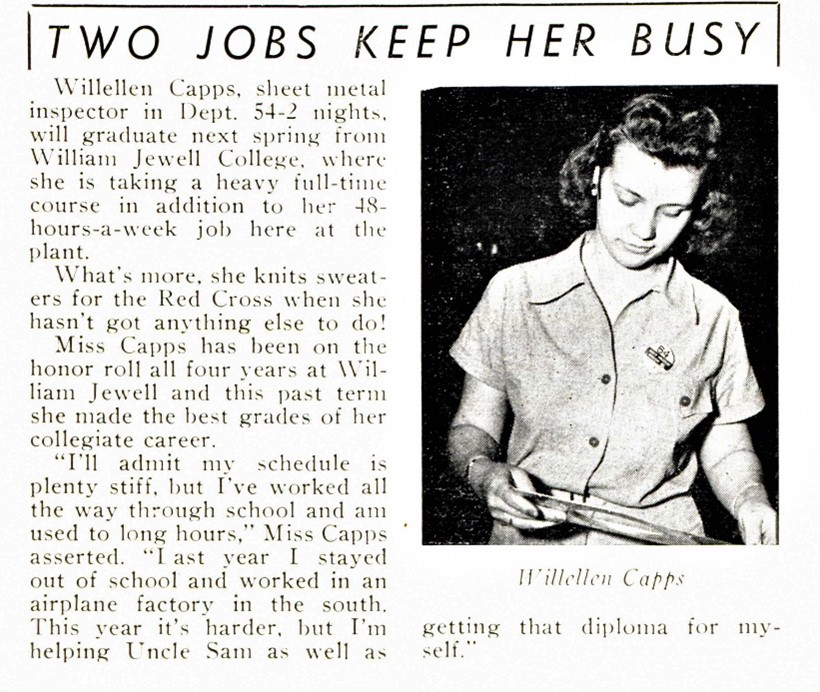

Life for factory workers was very busy. It wasn’t unheard of to work more than 40 hours per week. In 1943, Willellen Capps reported a 48-hour work week on top of her full-time course load at William Jewel College in North Ameri-Kansan. Still, she somehow found time for recreation, knitting sweaters for the Red Cross in her spare time.

Other women workers found ways to unwind, too. When Santina Brancato Catalina wasn’t putting together Double Wasp engines at Pratt and Whitney, she was helping her parents at their family business: Fairyland Park.

“It kept coming up in conversation” said Jody Valet in Rosie the Riveter Stories: How They Did It! Many of the women she met who worked in the factories like her grandmother had fond memories of Fairyland Park. They usually remembered the seaplane ride and its conversion to bomber planes during the war, too.

Fairyland Park wasn’t available to all factory workers, however. Segregation was still very much in place in the 1940s, at the park and in the factories. African Americans and whites worked side-by-side, but had separate dances and other company-sponsored leisure activities.

For four years, from 1942 to 1945, women kept American factories and workplaces running smoothly and efficiently. Despite their obvious skills and determination, however, many of them found themselves out of work as soon as the war ended. Lorene Norman Bailey, another NAA employee, remembered that day very clearly in How They Did It!

“The supervisor came around and told us the war was over,” she said. There was “complete silence” as all the machinery stopped. After a few days of inventory, the factory closed. Almost as suddenly as they had started, the women were unemployed.

As GIs returned from the war and the U.S. government pushed for a “return to normalcy,” women found new occupations. Some took other jobs. Many married and raised families.

Some women shared their wartime stories with their children and grandchildren; Jody Valet has fond recollections of her grandmother’s shared memories. Others, like Helen Sullinger, were totally surprised to learn they knew a “Rosie.” Her friend Vera Utz Noggle never mentioned it, even while serving as the VFW Auxiliary president.

Vera “took seriously the pledge of secrecy,” she explained in How They Did It!. “She’s still a home front patriot.”