What Happened to Kansas City’s Christmas Crowns?

With the holidays in full swing, a What’s Your KCQ? reader recently wondered: “What happened to the Christmas decorations that used to be displayed downtown, particularly the crowns strung across the streets?”

Since City Hall lacks an attic, we couldn’t start our search in the most logical place.

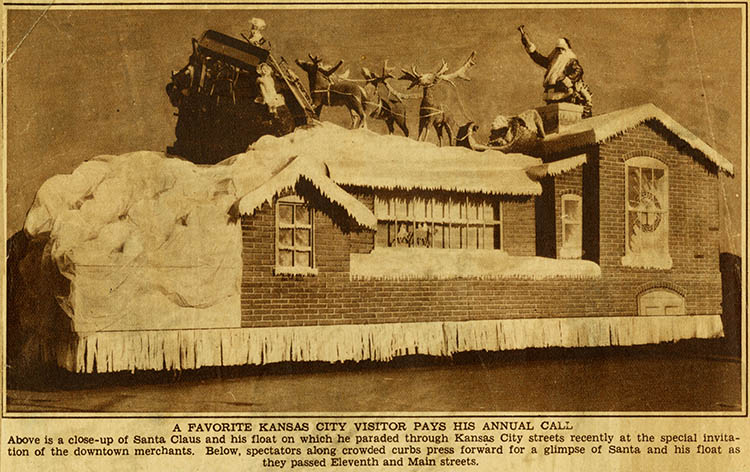

In the years before World War I, the downtown Christmas shopping season was a modest affair. The economic boom of the 1920s changed things, and beginning in 1924, the Downtown Merchants Association pooled its resources and festooned the streets with garland and other decorations. In 1925, the association added a parade to kick off the holiday season.

Business suffered during the Great Depression, and the parade was called off in 1930 and ’31. Coincidentally, the first organized lighting of Christmas lights on the Country Club Plaza occurred in 1930 — a sign of Christmas shopping trends yet to come.

Downtown retail was safe for the time being and remained stable through the 1940s. However, the economic surge that followed World War II was the beginning of the end. With plenty of affordable automobiles, it was possible to live further and further from the city. Easy access to home mortgages made the suburbs an increasingly attractive option.

And each year, fewer and fewer shoppers had the patience to deal with downtown parking and congested streets when they had their choice of newly built shopping centers and malls with spacious parking lots closer to home.

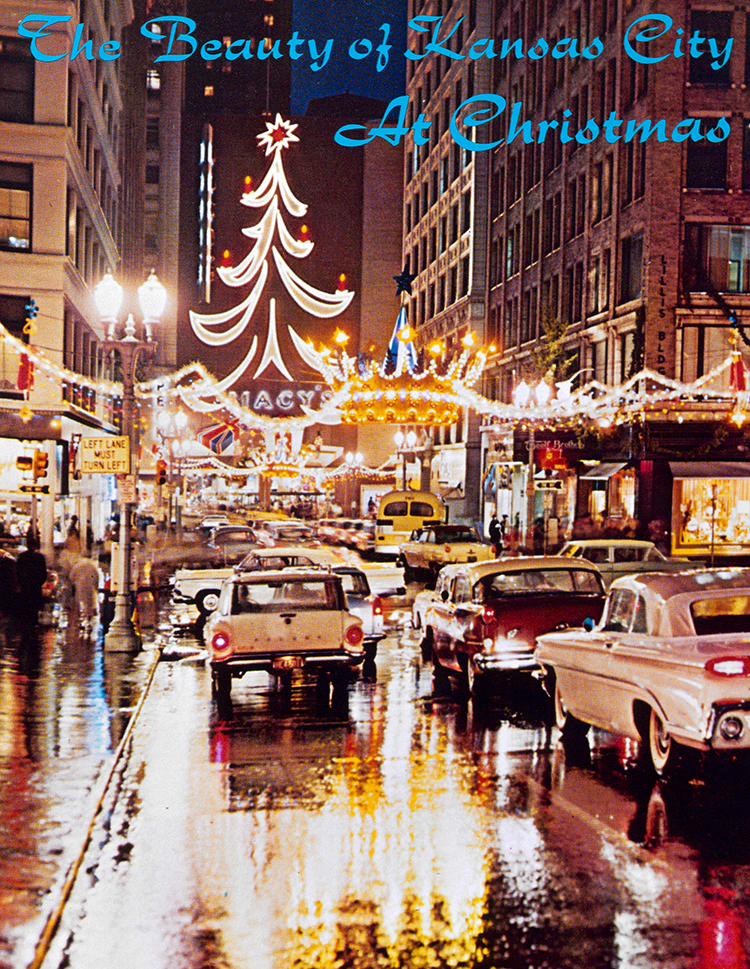

Hoping to create a unique Christmas shopping experience, the Downtown Merchants Association worked with two local retail display firms to entice customers to return.

George Purucker was the owner and operator of George Purucker Displays, Inc. On a trip to England one year during the holidays, he’d seen large, decorative crowns suspended above intersections in the Regent Street shopping district in London’s West End. By then in the 1960s, thanks to the American Royal, Kansas City was synonymous with crown iconography, and Purucker thought the concept was perfect for festive decorating. The DMA loved the idea.

Purucker’s daughter Ann later described the demanding work the family put into the original set of crowns. “I came home from school every day for weeks and made the streamers to attach each crown to the street corners in the basement of our Prairie Village home,” she said. “I measured every foot of wire, installed every light socket, and installed every single light bulb into the streamers.”

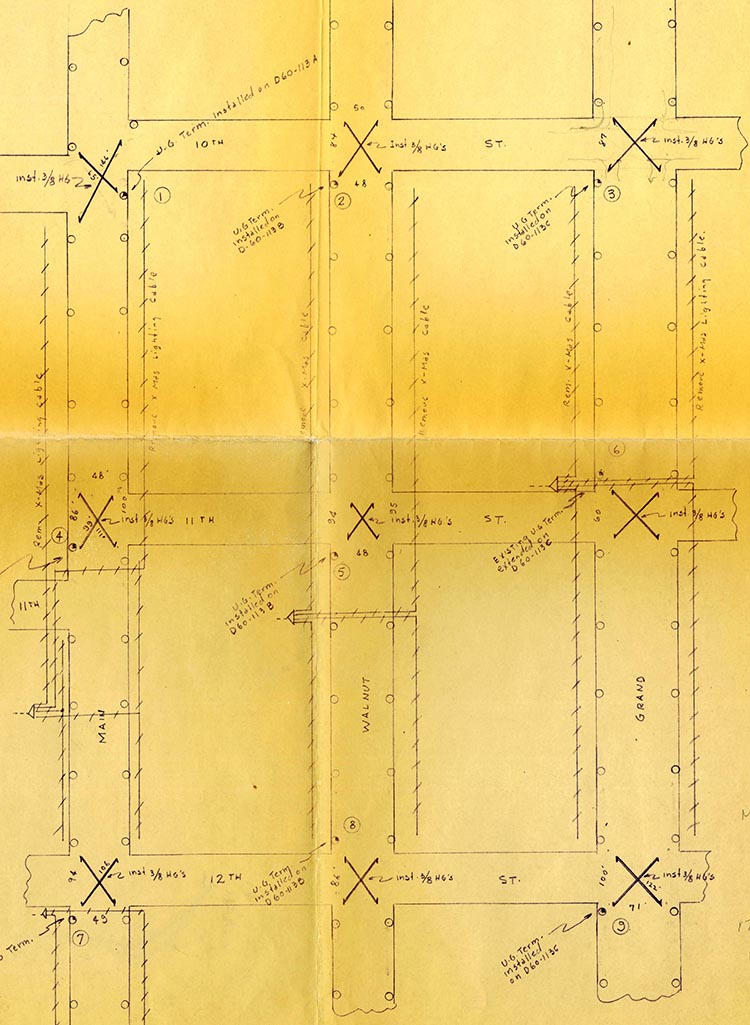

Frank Mann, of the Mannequin Company (later renamed Manneco, Inc.), was involved with the manufacture and upkeep of the crowns over the years. Constructed of gold-foil-wrapped aluminum frames, each crown was about 13 feet tall and 14 feet in diameter and weighed nearly a ton.

Adorning each was 1,621 bulbs that The Kansas City Star said could “light 30 homes.” The magical holiday glow from the crowns required so much electricity that each needed its own dedicated electrical transformer.

In a 1975 interview in The Star, Mann said he kept a protype of one of the crowns in his office.

Ann Purucker said her father oversaw their original installation in 1962 — the streamers for each uniquely sized to accommodate variations in building and street dimensions. She recalled that workers who mounted the crowns in subsequent years, lacking her father’s “meticulous standards,” must have been unaware of which streamers went with which crowns because, to her, they always appeared a bit off.

The original nine crowns went up each Christmas season through 1966. The winter elements were hard on them, and lighter and more energy-efficient fixtures were made for subsequent seasons. The DMA also ordered a set of smaller crowns that were mounted to streetlights.

Kansas Citians loved them. But the crowns were up for only about a month each year, and downtown retail continued its decline through the 1970s. They made their final appearance for Christmas 1976.

Changes to the city’s architectural landscape also helped push them into retirement. Suspending the crowns above busy intersections required a building at each corner, and with Kansas City deep in the urban renewal era, structures in the downtown shopping district were coming down fast.

The explosion of suburban malls in the 1970s and ’80s drew even more shoppers away. Emery, Bird & Thayer, a staple of shopping along Petticoat Lane (11th Street), closed its doors in 1968. Harzfeld’s, another Kansas City retail institution, held on until 1984. It would take the opening of the Power & Light District in 2007 to attract holiday shoppers back to downtown on a significant scale.

The larger iconic crowns were put into storage. The smaller streetlight crowns continued to appear until the early 1980s, when the Downtown Merchants Association did not provide funds to light them. They eventually were sold to the city of Kansas City, Kansas, and used to decorate its downtown streets through the early 1990s.

It was reported that the larger crowns were sold again to the city of Holton, Kansas, to be repurposed as jungle gyms. However, in 2004, The Star wrote that no one in the Holton city clerk’s office — even the “old-timers” — had any memory of the purchase, nor of any crown-shaped playground equipment in the city.

While the downtown Christmas crowns are lost to time, Kansas Citians can recreate the experience today. A replica hangs inside the Commerce Bank building at 1000 Walnut Street. Unlike its predecessors, this modern-day version weighs a mere 392 pounds and uses energy efficient LED lighting.

In 2004, Zona Rosa revived the tradition with a new set of crowns modeled after their 1960s predecessors. Several are suspended above key intersections in the Northland shopping center each year.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.