Western Auto: A Sign of the Times

The bold, bright Western Auto sign is an iconic piece of Kansas City’s downtown skyline and central to a recent What’s Your KC Q inquiry: How did the Western Auto company get its start here, and how was it tied to the distinctive, 12-story building that still bears its name? The sign went dark for many years, inviting another question: Why was such an eye-catching element of our night sky allowed to fall into disrepair? To understand, we must begin with the story of a young bookkeeper with plans to make it big in Kansas City.

George Pepperdine was born in 1886 in Mound Valley, Kansas. His family later moved to nearby Parsons, where he attended a business college. After graduating, Pepperdine came to Kansas City to start his career in bookkeeping. Finding work with the Regent Tire Company, he couldn’t help but notice a new fad sweeping the nation, the new Ford Model T automobile.

Introduced in 1908 shortly after Pepperdine’s arrival in Kansas City, the Model T was the first car that average consumers could afford. Demand soon grew for aftermarket parts for the “Tin Lizzies,” as Model Ts came to be known, and Pepperdine started a mail order parts business from his home to meet it. His wife Lena pitched in, helping to pack orders for shipping. Business was good, and Pepperdine soon gave up his bookkeeping position to exclusively focus on his Western Auto Supply Agency.

By 1910, Pepperdine had moved his thriving cottage industry to its first official headquarters at 708 E. 15th Street. A few years later, the first Western Auto retail store opened at 1426 Grand Avenue in today’s Power & Light District.

The only thing that could slow the company’s rise was its founder’s health. In June 1914, Pepperdine was diagnosed with tuberculous. He convalesced in Denver and, finding the mountain climate agreeable, decided to stay. Also finding the business climate hospitable, he opened a new Western Auto store there. By 1916, Pepperdine had sold his interest in the Kansas City company and relocated anew to southern California. The two separate firms that he’d founded reached an agreement: Pepperdine’s Western Auto of California would operate in 11 western states while Western Auto of Missouri would focus on the Midwest and South.

Pepperdine retired in 1939, selling his California-based company to the Gamble-Skogmo Company. The two Western Auto enterprises continued to peacefully coexist and ultimately merged in 1955.

Two years prior to his retirement, a public university bearing Pepperdine’s name was founded in Malibu, California. Despite ailing health, he devoted much of his time to George Pepperdine College, later renamed Pepperdine University, and to philanthropic and church activities. Pepperdine passed away July 31, 1962.

Back in Kansas City, Western Auto of Missouri continued to gain steam. In response to a decline in mail-order trade, the company launched a major expansion of its retail stores in 1919, putting down stakes as far to the north as Saint Paul, Minnesota, and as far south as Dallas, Texas.

But to tell the story of the Western Auto Building, we must turn our attention to another ascendant company with an equally recognizable logo.

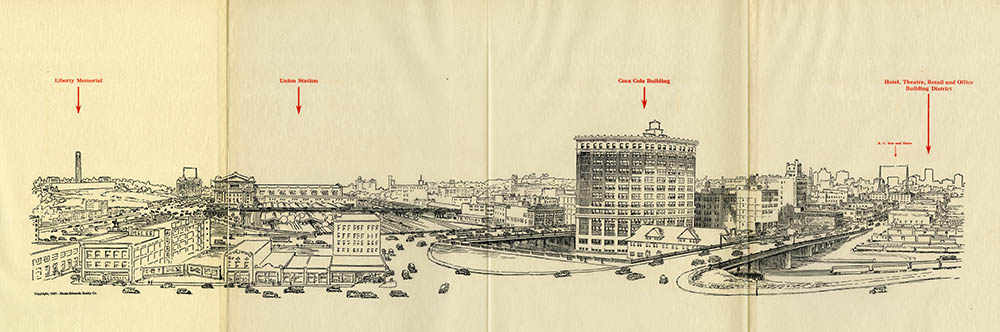

In addition to demand for automobiles, soft drink sales exploded in the early 20th century. In 1909, The Coca-Cola Company of Atlanta selected a site in Kansas City as the home of its new west-central distribution branch. The middle-of-the-country location, access to rail lines, and plans for a new Union Station mere blocks away convinced Coca-Cola President Asa G. Candler that he’d made the right decision.

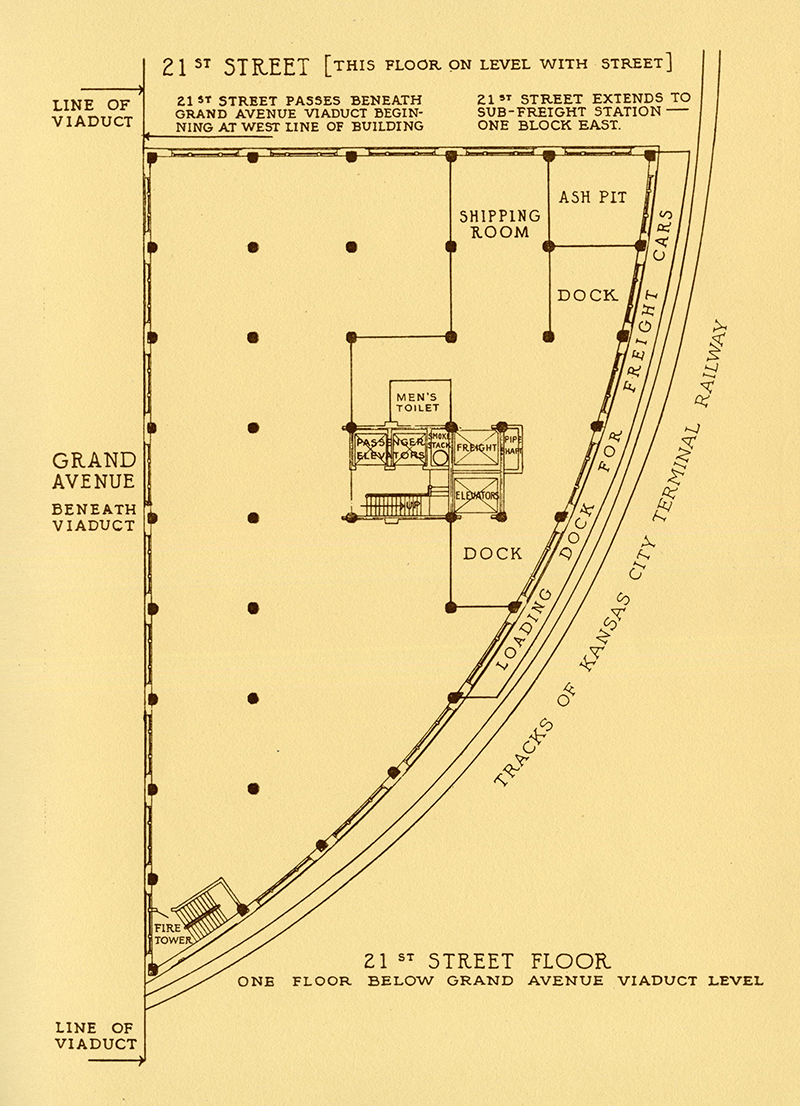

Baltimore architect Arthur Tufts, the head of construction for Coca-Cola, designed an up-to-date office and warehouse building within the confines of a rather oddly shaped lot hemmed in by the tracks of the Kansas City Terminal Railway. Making the job more difficult, the triangular building would need access to streets and rail lines at differing elevations on each of its three sides: the Grand Avenue Viaduct on the west, 21st Street on the north, and the railroad tracks along its curved southeast side. Tufts, who had designed landmark buildings across the country, pulled off what is now regarded as one of his most intriguing creations.

Completed in 1915, the building was originally crowned with a Coca-Cola sign that would remain a downtown fixture until its removal in 1928. In December of that year, a still- expanding Western Auto leased the entire 11th floor of the Coca-Cola Building. It occupied more and more space before purchasing the building in 1951. By June 1952, the firm had invested over $300,000 in renovations and additions, including a new 30-ton, 70-by-73-foot sign displaying its name in massive red letters encircled by an arrow.

With the merger with Western Auto of California in 1955, the Kansas City-based company had officially become a national brand. Western Auto remained at 2107 Grand over the decades, employing more than 1,000 Kansas Citians by the 1960s. However, economic forces sent the company into decline by the early 1980s.

Following cutbacks, the company was sold to Sears Roebuck in 1988. A decade later, the subsidiary was purchased by Advance Auto Parts, which consolidated operations and put the building up for sale. In January 2000, what remained inside the building was sold at auction and the sign was switched off – to be relit only occasionally, and in those instances briefly, over the next 18 years.

The building languished on the market until 2002, when a real estate development group purchased it and announced a plan to convert the former office and warehouse building into luxury condominiums. A year later, the first units went up for sale. The project was a hit. There was no shortage of eager buyers willing to take a gamble on life in a downtown area in its earliest stages of revitalization.

Yet, the sign remained dark.

That was until 2018. And then, it required more than a mere flick of the switch. After nearly two decades of dormancy, the sign needed extensive repairs and upgrades.

The Western Auto Lofts homeowners’ association met the challenge. “The association is thrilled to give this gift back to the residents of Kansas City and can’t wait to be a part of the skyline once more,” said the group’s press release. The assigned contractor, Infinity Sign Systems, had to sort through approximately 2,500 incandescent bulbs, 1,000 feet of neon tubing, and miles of wiring to convert to the use of more energy-efficient LED bulbs.

Finally, at 8:45 p.m. on Friday, July 13, 2018, the switch was hit and Kansas City’s downtown skyline was graced once again by Western Auto’s warm, electric glow. All thanks to a group of downtown residents, and of course, a young auto parts salesman with a dream.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.