Urban Demolition Leads to Preservation

Platted and developed during a citywide building boom at the turn of the 20th century, Kansas City’s Hyde Park neighborhood boasts not just one, not two or three, but four areas added to the National Register of Historic Places between 1980 and 2007.

That answers the first part of a What’s Your KCQ question from reader John Skelton, who wondered when the midtown enclave had earned that designation. And further: Why? His inquiry prompted a deeper look into the historic preservation movement, encompassing protests in New York, the scars of urban renewal, and changes to tax law that nudged developers away from demolition and toward renovation.

All told, KC’s Hyde Park area extends from 31st street south to 47th street between Gillham Road and Troost. Most of its 1,500 homes and assortment of well-preserved apartment buildings were built between 1900 and the early ’20s.

South Hyde Park is the most recent addition to the National Register, listed in November 2007. The old Hyde Park East and West districts had been added more than three years earlier, in May 2004.

It was the quaint heart of the neighborhood, Central Hyde Park, that first drew preservationists’ attention, landing it on the Register in November 1980.

Its single-family homes feature a potpourri architecture styles, from Colonial Revival, Shingle Style, Queen Ann, Bungalow, and Prairie School to an iconic local favorite, the Kansas City Shirtwaist stone and wood hybrid. The area surrounds tonier Janssen Place and nestles against its namesake greenspace, Hyde Park, which was one of the first Kansas City designs by noted landscape architect and urban planner George Kessler.

National Register nominators cited more than 300 “significant structures” that remained virtually intact from their turn-of-the-century construction.

“The park and neighborhood have survived with very few changes in their original appearance,” the nomination said, “making the Hyde Park one of the best preserved examples of early 20th century residential design and planning in Kansas City.”

Just what the National Register was designed to protect.

Came in Like a Wrecking Ball

Substantial changes to American cities during the 1960s demonstrated what could happen when communities allowed the wrecking ball to erase historic structures. The most notable case came in New York City in 1963, when architects and other preservation-minded citizens lost a battle to save iconic Penn Station from demolition and replacement.

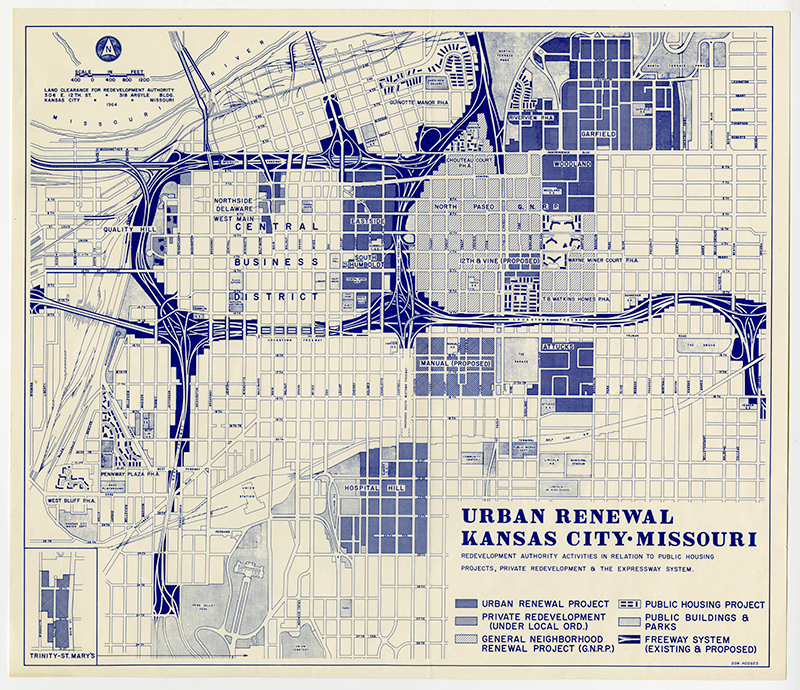

In Kansas City, urban renewal projects demolished entire neighborhoods to create a system of highways connecting new suburban areas with the downtown core. The 1960-era urban renewal map shows the targeted areas.

Highways and such civic infrastructure as public housing and transit centers were the most obvious forms of urban renewal. But private redevelopment projects – like those on the map – also led to a loss of meaningful architectural history at the neighborhood level.

Changes were most notable in Kansas City’s historic Northeast, where mansions along Independence Avenue and other historic boulevards were torn down or replaced during the 20th century. Wealthy residents left the Northeast for planned communities in then-new Country Club and Brookside areas, drawn south to (relatively) smaller modern homes without servant quarters.

A number of new planned communities featured restrictive homeowner policies, including racial covenants that maintained segregated neighborhoods. Meanwhile, lacking affluent owners to pay for their considerable upkeep, many large estates in the Northeast fell into disrepair and were demolished.

Rise of the Historic Preservation Movement in Kansas City

By the late 1960s, the costs of urban renewal became clearer to citizens and officials in charge of America’s cities. The value of preservation was spelled out in 1966 in a report from the U.S. Conference of Mayors, which made the case for conserving historic neighborhoods because of their significance to city identity and character. A special committee on preservation proposed a comprehensive system for evaluating and registering historic places and neighborhoods. Less than a year later, on October 15, 1966, Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Historic Preservation Act.

But the National Register was an imperfect device. Listings merely noted a building’s or neighborhood’s historic character and value and did not offer funding for restoration or provide protections. It was more a status symbol than a functional means of preservation.

Concerned citizens formed the Historic Kansas City Foundation (HKCF) in 1974 as a not-for-profit group dedicated to conserving the city’s architectural heritage. It began its mission by surveying downtown buildings to identify their historic value and then advocated for their preservation.

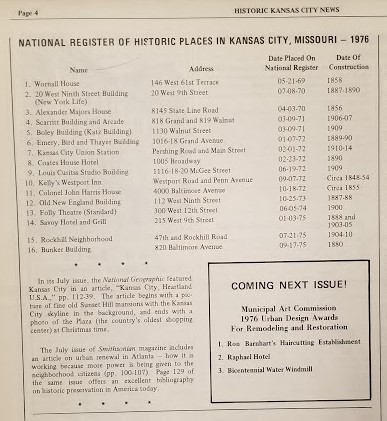

The foundation worked closely with Kansas City’s Landmarks Commission, which had been established in 1970 after several years of debate. Looking to save the city’s urban core, HKCF drew initial support from the philanthropic community and eventually popular support through Old Possum Trot festivals. The foundation’s newsletter, The Historic Kansas City News, celebrated local additions to the Historic Register.

Your preservation hero is … the Tax Code?

Initially, a listing on the National Register (or the Kansas City Register) did not add much to a property’s value. That changed with passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1976, which provided generous incentives designed to make historical preservation more financially attractive than demolition and redevelopment. Individual buildings on the Register, or those contributing to the historic integrity of a listed district, were granted special tax write-offs. The law also eliminated several tax breaks that encouraged demolition.

The incentives led to a proliferation of historic district designations. The first districts in Kansas City –Janssen Place and the West Ninth Street and Baltimore Avenue area – were listed on the National Register in 1976. They were followed by the Wholesale (Garment) District in 1979 and Central Hyde Park in 1980.

In the past 40 years, property owners in Jackson County have successfully nominated more than 50 districts for the Register. Many are home to architecturally significant structures. Others, like the Harry S. Truman district, are identified with historic individuals. Even multi-unit housing has gotten love: Three large, post-World War II apartment buildings were added to the National Register in 2005. Using tax credits arising from their listing, developers successfully converted these formerly dilapidated hulks into financially viable units.

Curious about the buildings that make a district historic? You can view nomination forms for all of Kansas City’s listings on the National Register at the Missouri Department of Natural Resources website. The forms include descriptions of contributing properties and an explanation of their architectural and historical significance.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.