Unionization Comes to the Slaughterhouse

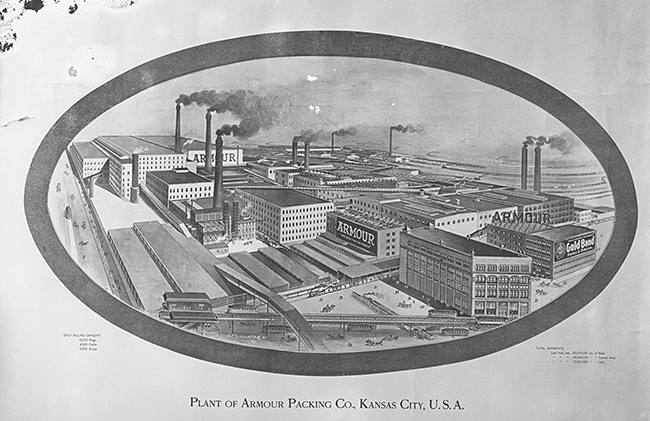

In the late 19th century, livestock and meatpacking industries had spurred Kansas City’s growth into an industrial giant. Almost 200,000 miles of railroad tracks covered the United States, and the refrigerator car had been patented, improved, and nearly perfected. This gave the meatpacking industry a huge boost, which in turn created the need for more workers along every step of the slaughterhouse process.

By 1920, the meatpacking industry was one of the nation’s biggest contributors to the gross national product and one of Kansas City’s largest employers. Industrialization allowed meatpackers to employ unskilled labor for jobs previously occupied only by skilled butchers. The craft unionism of the 19th century that excluded so many workers became less effective, and inclusion and common goals became the laborers’ motto. Thus, industrial unionism was born on the killing floor.

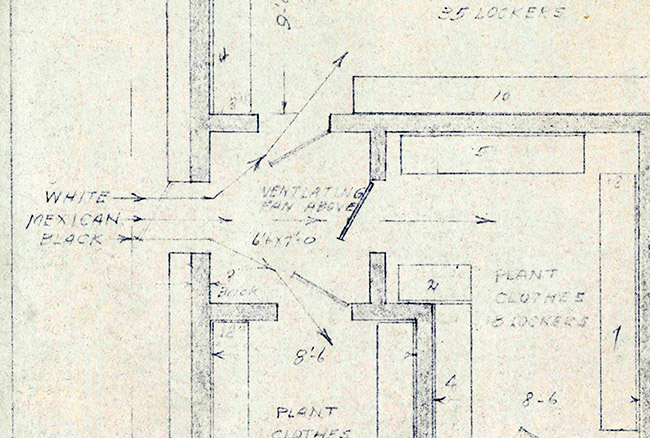

People of varying ethnic and racial identities flocked to the West Bottoms to fill the plentiful, competitive paying jobs these industries provided. Yet no regulation of working conditions existed and jobs at the packing plants were dangerous. Although each of the “Big Four” meatpackers (Armour, Wilson, Cudahy, and Swift) had plants in Kansas City, wages and working standards were set for the entire nation by their plants in Chicago. This made Chicago the center of the union struggle, but union presence in Kansas City was unlike that of any other city.

Although an adamantly segregated city, Kansas City accepted African Americans in its slaughterhouses earlier than any other city. African Americans elsewhere gained their foothold in the meatpacking industry during World War I, but here ex-slaves had been migrating to the Armour Packing plant since it opened in 1870.

While meatpacking plants allowed African Americans to fill relatively well-paid positions, only a small percentage of other Kansas City businesses would employ them. Other ethnic groups and minorities, such as immigrants from Eastern Europe and women, also were given more job opportunities in the meatpacking district than elsewhere in the city. Once the workday was over, individuals from each ethnic group would go home to their own communities, but during work hours they worked for a common goal that bonded them. Although the work was difficult, especially for those on the killing floor, slaughterhouses paid decent wages and offered room for advancement for an unskilled, ethnically diverse part of the Kansas City population that had few other options.

Prior to the 1930s, there was no cohesive industrial unionism. Instead, unions were organized according to particular crafts – for example, the United Mine Workers and the Amalgamated Meat Cutters – and only open to those within their respective crafts. Another issue with forming an industrial union was how to bring African Americans on board. In response to the segregation they faced, the African American community formed a very cohesive and organized force. Their loyalty though, lay with the packing plants’ management, which provided opportunities rarely available elsewhere. Another point of contention: The meatpackers often employed African Americans as strikebreakers, undercutting the unions’ ability to bring about change.

Efforts to unionize were made starting in the late 19th century. But it wasn’t until the 1930s, when economic depression and labor unrest were sweeping across the nation, that workers of all qualifications realized their shared dissatisfaction.

Congress enacted the Wagner Act in 1935, establishing the right of workers to organize and bargain collectively and outlawing unfair labor practices that often had kept union membership down. In 1937, the Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee (later renamed the United Packinghouse Workers of America) was established and gained a considerable foothold in the Great Plains states.

The PWOC was an inclusive organization that actively recruited laborers from all jobs in the packinghouse, including African Americans. This was especially true in Kansas City, where a group of Socialists led by Charles Fischer served as a rallying force in bringing the African American community into the union folds.

The 1930s brought a new wave of industrial unionization and, in Kansas City especially, where Fischer was leading the charge, the full potential of unprejudiced organization was made a reality. Fischer’s affirmation that “without a union, we’re all lost” seemed to resonate with the workers who represented the progressive and interracial spirit of the time.

A successful 1938 strike at the Kansas City Armour plant, led by the PWOC, served to solidify the union’s interracial alliance. The union continued its committed support of inclusiveness, even publishing and distributing a booklet in 1952 titled “Action Against Jim Crow” as part of its anti-discrimination policy.

As the meatpacking industry thrived and industrialization took hold, the need for regulation and management accountability became ever more apparent. Attempts were made to organize labor unions within the meatpacking industry, but the lack of cohesion between separate worker groups hampered efforts for decades. The local union chapters in Kansas City remained more stable than their counterparts in Austin and Chicago, largely due to their successful campaign for inclusive unionism, which brought together all groups in all union activities.

References:

Brody, David. The Butcher Workmen: A Study of Unionization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964.

Coulter, Charles E. Take Up the Black Man’s Burden: Kansas City’s African American Communities, 1865-1939. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2006.

Horowitz, Roger. “Negro and White, Unite and Fight!” A Social History of Industrial Unionism in Meatpacking, 1930-90. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Pate, J’Nell L. America's Historic Stockyards: Livestock Hotels. Fort Worth, TX: TCU Press, 2005.

Ramos Vertical File: Bunche, Dr. Ralph; 'Equal Rights' Booklet Is Published

Skaggs, Jimmy M. Prime Cut: Livestock Raising and Meatpacking in the United States, 1607-1983. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1986.

Warren, Wilson J. Tied to the Great Packing Machine: The Midwest and Meatpacking. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2007.