Tragic Turn: KCQ Revisits Historic Cliff Drive

A previous KCQ on the history of Cliff Drive was a trip down memory lane for many Kansas Citians.

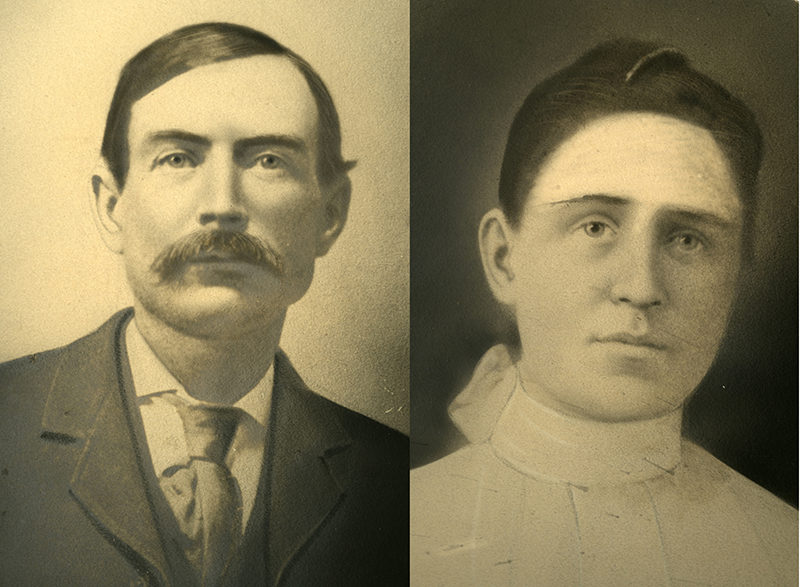

Evelyn Hougland of Olathe, Kansas, reached out to the Library to share a personal connection her family has with Cliff Drive. Her grandfather, John Francis Mahoney, was the final contractor hired to complete the picturesque road through Kessler (formerly North Terrace) Park in 1905.

In a tragic twist of fate, the recreational roadway that was one of Mahoney’s proudest achievements would also cost him his life and have a profound impact on his family for generations.

Completing Cliff Drive

As Kansas City’s population and economy grew in the 1880s and ‘90s, so too did its geographic footprint. New roads and streetcar lines linked to neighborhoods east and south of downtown and a newly formed parks commission put forth an ambitious plan, spearheaded by landscape architect George Kessler, to develop spacious city parks connected by scenic boulevards.

For contractors, builders, and others in the construction trade, business was booming.

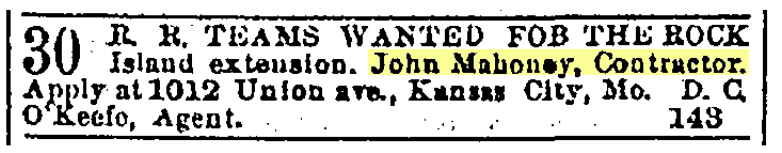

John Mahoney was an established contractor when construction of Cliff Drive began in 1899. He oversaw major road and railway projects on both sides of the state line, such as grading and paving sections of Swope Parkway, Southwest Boulevard, Wornall Road, Kansas Avenue, and other thoroughfares. Mahoney was also credited with constructing nearly every rock road in Wyandotte County before the turn of the 20th century, as well as many in Johnson County.

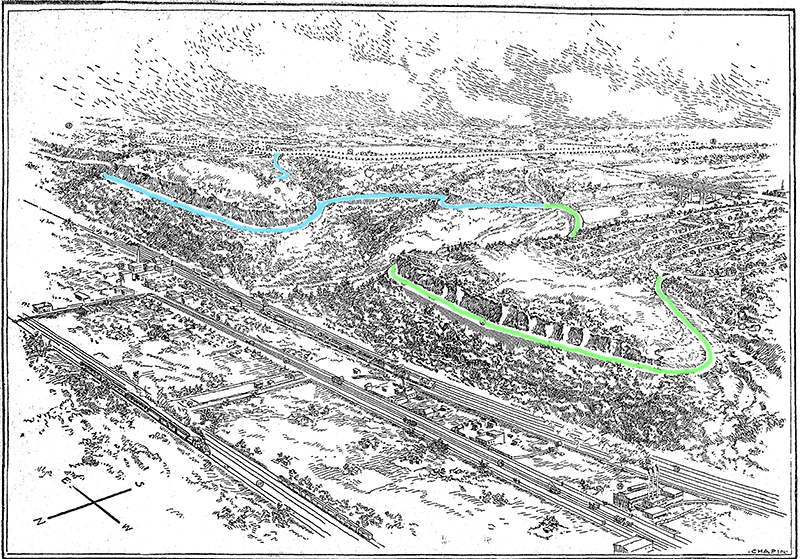

After the first section of Cliff Drive opened in 1900, Kessler began designing an extension through North Terrace Park’s west side, which he originally referred to as “Riverview.” Kessler’s plan called for not only connecting the east and west park regions, separated by a deep ravine, but providing another entrance to Cliff Drive and additional views of the Kaw and Missouri River valleys below.

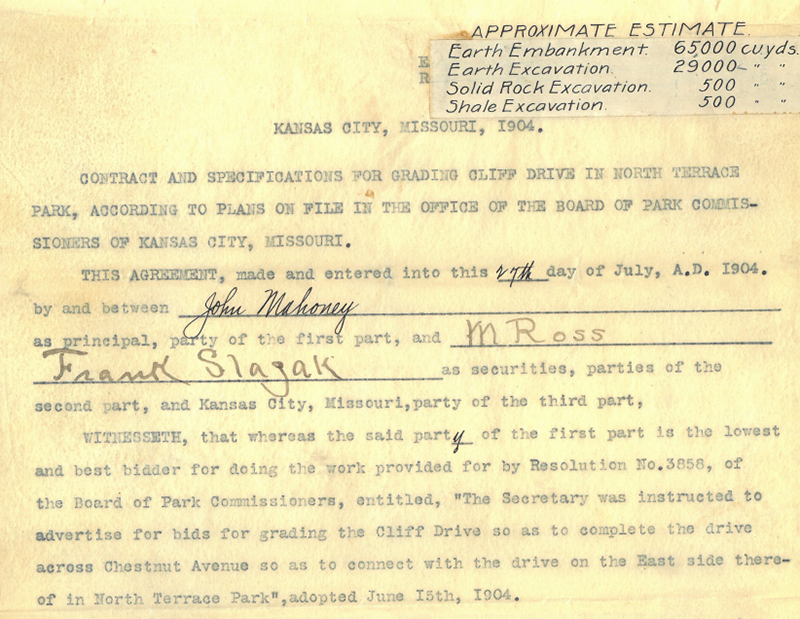

The sale of $200,000 in bonds in June 1904 allowed for extensive improvements to the city’s emerging parks and boulevards system, including the completion of Cliff Drive. Bids were sought for the grading and John Mahoney was awarded the job. A contract was signed July 27, 1904, and work began to link west Cliff Drive with the already completed route ending at Chestnut Avenue.

Construction of the western route was an arduous undertaking. In several places along the bluff, some with sheer drops of more than 200 feet, workers blasted rock away to clear room for a road wide enough to accommodate vehicle traffic.

Nearly a year to the day when Mahoney signed the grading contract, a public grand opening celebrated the opening of the completed west extension. The new Cliff Drive was a signature attraction of the city drawing thousands of visitors by foot, carriage, and automobile.

Joy Ride

When not constructing roads, John Mahoney enjoyed driving them. In 1909, he purchased a seven-passenger Pierce-Arrow motor car for taking leisurely rides with family and friends.

The vehicle formerly belonged to a local widower, Mrs. Mary Dickerson, who raised eyebrows in the early 1900s for amassing a collection of expensive automobiles and frequently being cited for speeding. When Dickerson died in 1909, her automobile collection was auctioned on the steps of the downtown Federal Building, where Mahoney was the high bidder at $3,500 for her Pierce-Arrow touring car.

Automobile ownership at the time was a luxury available to only a small number of Kansas Citians. Mahoney was not born into wealth, however. He came to Kansas City at age 15 with his widowed mother and worked as a laborer. He eventually saved enough to buy horses and equipment and go into business for himself. By 1900, he was one of the largest contractors in the area.

Mahoney’s friends noted that he spent much of his free time behind the wheel of his red Pierce-Arrow—a reward to himself and his family for years of hard work and business success.

On Monday, January 24, 1910, Mahoney invited a few of his employees for a ride around the city. Two of his foremen, Thomas McGuire and John O’Connor, arrived later that day at the Mahoney residence in Kansas City, Kansas. Six passengers in all—John Mahoney, his wife Ellen, two of their daughters, Nellie (19) and Lillian (6), and McGuire and O’Connor—set off for downtown Kansas City, Missouri. The two other Mahoney children, Anna (13) and John Jr. (9) were at school and did not join them.

As the riders crossed the Intercity Viaduct into Missouri, McGuire suggested a tour of Cliff Drive.

Tragic Turn

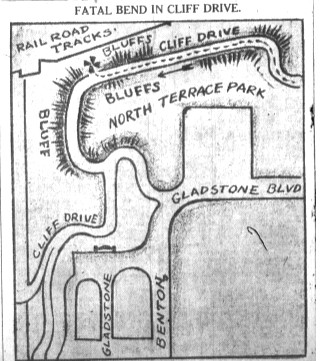

A cold January afternoon was not an ideal time to travel Cliff Drive’s winding route alongside steep cliffs. It was common for water to trickle down to the road from the bluffs above and freeze. The same bluffs kept the roadway shaded much of the day, creating treacherously icy conditions. But Mahoney had driven the route many times previously and knew it well. He entered the drive’s eastern terminus at Gladstone Boulevard and Elmwood Avenue and proceeded westward.

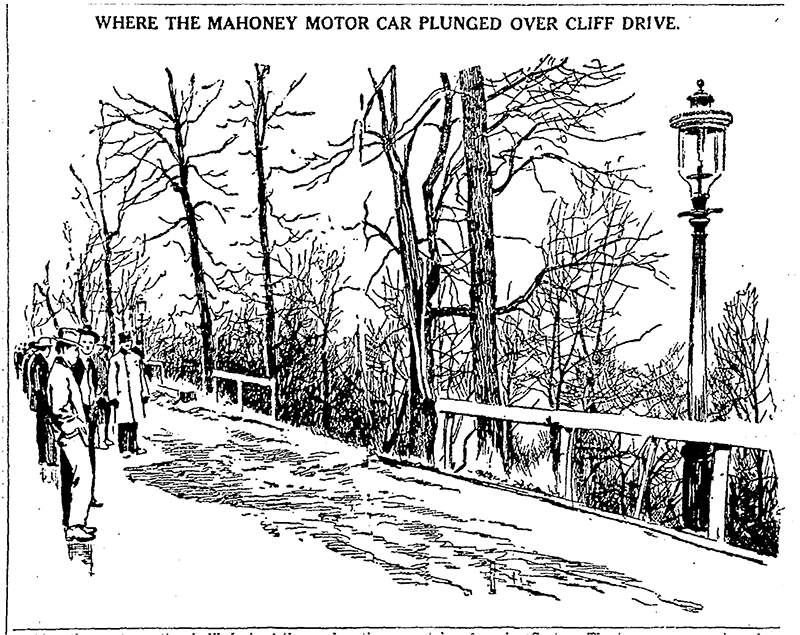

It was on the stretch of Cliff Drive below Scarritt’s Point where Mahoney, approaching a turn, hit a patch of ice and skidded. Panicked, he jerked the steering wheel sharply inward to veer away from the road’s edge. Unable to stop the vehicle’s momentum, the rear end swung around and shot toward the fence and the abyss beyond.

The Kansas City Post reported, “There was no time to jump. The rear wheels tore through the fence as if was a gingerbread toy. The car turned a complete somersault in the air and dashed itself to pieces on the boulders below.”

"O, God! O, God!"

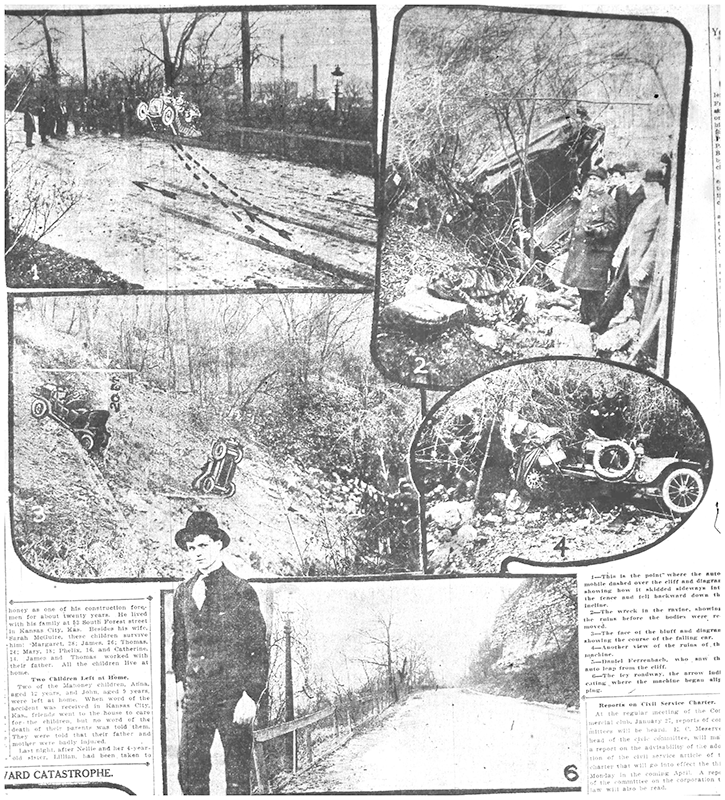

Nineteen-year-old Daniel Fehrenbach was chopping wood in the valley below Cliff Drive when he heard a woman scream. Looking up, he saw Mahoney’s automobile turn over in the air and fall 80 feet down the hillside before landing with a loud crash. Moments later, a man’s voice cried out “O, God! O, God!”

A young boy, Thomas Nelligan, was also nearby and he and Fehrenbach ran towards the crash site.

Another man, M.G. Gibson, was walking the railroad tracks far below Cliff Drive when he, too, heard a crash followed by screams and went to investigate.

The scene they encountered was horrific.

The man shouting was John O’Connor, whose leg was pinned under the vehicle. He had been seated in the back with Ellen Mahoney and her two daughters. Ellen died within minutes of the crash. Nellie and Lillian were alive but critically injured. John Mahoney and Thomas McGuire perished upon impact.

Lillian clutched a doll whimpering as Fehrenbach and Gibson helped her away from the wreckage and wrapped her wounded head with handkerchiefs. They also comforted the older sister Nellie who was seriously injured and in shock.

After freeing O’Conner from under the car, help was sought at a nearby police station on Guinotte Street.

The survivors were taken by ambulance to St. Margaret’s Hospital. The youngest Mahoney daughter, Lillian, was gravely injured and slipped into a coma. Her older sister Nellie was in critical condition with multiple fractures and internal injuries.

Miraculously, John O’Connor sustained only bruising and mild head trauma, and was up and walking shortly after the accident. He was released from the hospital later that day.

A subsequent investigation of the accident concluded that Mahoney likely cut power to the engine in a vain effort to stop the vehicle from hitting the fence. This likely kept the car from catching fire upon impact and killing all the occupants.

Funeral services for John and Ellen Mahoney were held at the family home on January 28, 1910. The couple was buried in St. John’s Cemetery in Kansas City, Kansas. Nellie and Lillian survived their injuries after an extended hospital stay.

Devastated by the loss of their parents, the four Mahoney children found themselves suddenly orphaned. Nellie was the only adult child and remained at the Mahoney home. Anna and Lillian were sent to the Mount St. Scholastica School in Atchison, Kansas. Their brother, John, also finished his schooling in Atchison at the St. Benedict School. Judge Michael Ross, a friend and business partner of Mahoney’s, gifted $50,000 to the children and paid off the family’s debts.

The siblings unsuccessfully sued the city a few years later arguing that the wood guardrails installed along Cliff Drive were inadequate protection for motorists. Despite the verdict, more rounded turns and stone wall barricades were added to the drive in the years following the fatal accident.

A Painful Memory

Lillian would eventually marry and have a daughter of her own, Evelyn. Decades after the wreck, she could still barely bring herself to discuss the tragic loss of her parents.

Evelyn later tracked down Daniel Fehrenbach, the young man who witnessed the accident and helped tend to her mother. The tragedy still haunted him as well.

When Evelyn asked her mother if she wanted to meet the man who helped rescue her, she politely declined. The accident and loss of her parents were just too painful a memory to relive.

How We Found It

Detailed accounts of the accident and casualties were published in The Kansas City Star and Times, Kansas City Journal, and Kansas City Post newspapers. Information about John Mahoney’s contract with the city to construct west Cliff Drive was found in the archives of the Kansas City Parks and Recreation department. Details about the Mahoney family were provided by John Mahoney’s granddaughter, Evelyn Hougland, and great-granddaughter, Ellen Hougland. We thank the Houglands for sharing their family’s story.

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.