‘Reasonably safe’: KCQ investigates Kansas City’s 1954 nuclear attack drill

Following a recent viewing of “The Day After,” the 1983 film depicting the destruction of Kansas City by nuclear attack, a reader wondered if the city was really considered a Soviet target during the Cold War years. In the movie, survivors of the attack witness the breakdown of society in rural Kansas and Missouri.

The individual put the question to What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, also asking if the city did anything to address the threat.

Indeed, as a major city with more than 40,000 manufacturing jobs, Kansas City was in the Soviets’ crosshairs. A 1955 federal report listed it as one of 70 critical areas in the continental United States extremely likely to be targeted in the event of war. All capital cities not meeting this benchmark were considered probable targets.

In the decades to come, the numerous intercontinental ballistic missile silos in the surrounding area only increased the likelihood of Kansas City being at risk if nuclear war erupted.

The Soviet Union became an atomic power in 1949 and tested its first hydrogen bomb in 1953. To “protect life and property in the United States in case of enemy assault,” President Harry Truman established the Federal Civil Defense Administration in 1950.

In addition to producing educational films like "Duck and Cover,” the new department’s efforts filtered down to citizens through local civil defense offices. In Kansas City, retired Army Brig. Gen. Charles O. Thrasher was placed in charge of getting the populace ready.

Thrasher, a veteran of both world wars, began speaking to civic organizations and other groups to communicate the need for urgent preparation for a Soviet attack. He warned that “interest is likely to wane unless the possibility of disaster is pointed at continuously.”

In addition to apathy, Thrasher was concerned about local architecture, infrastructure, and even geology. He concluded that there simply weren’t enough three-story basements in the city to provide shelter in the event of an attack and unlike other metropolitan areas, Kansas City lacked underground structures like miles of subway tunnels in which citizens could hide. He also pointed out that the deposit of bedrock beneath the city would reflect and exacerbate an atomic blast’s shockwave and cause numerous buildings to collapse.

Duck and cover didn’t seem like such a great plan.

On March 17, 1953, the threat of nuclear war was brought into American homes in a new way when a test of an atomic bomb was nationally televised for the first time. Civil defense planning accelerated.

By 1954, Thrasher had outlined an emergency plan to evacuate the downtown area’s daytime residents to safety outside the city. His team worked with medical professionals, civil defense block captains, specially trained radiation crews, and even amateur radio operators to learn how they could help in the event of an attack.

Civil defense offices in other cities suggested elaborate survival kits including things like fishing gear and dehydrated food. So-called civil defense picnics were held so families could practice preparing meals in the field.

Thrasher’s office was more modest, recommending only enough supplies to help families survive for 48 hours following an attack — just enough time for federal forces to respond. Pared-down kits were to include one bar of soap, antiseptic solution, a triangular bandage, a flashlight with batteries, a pocketknife, one tea towel, one bath towel, and enough hard chocolate to last a family for two days.

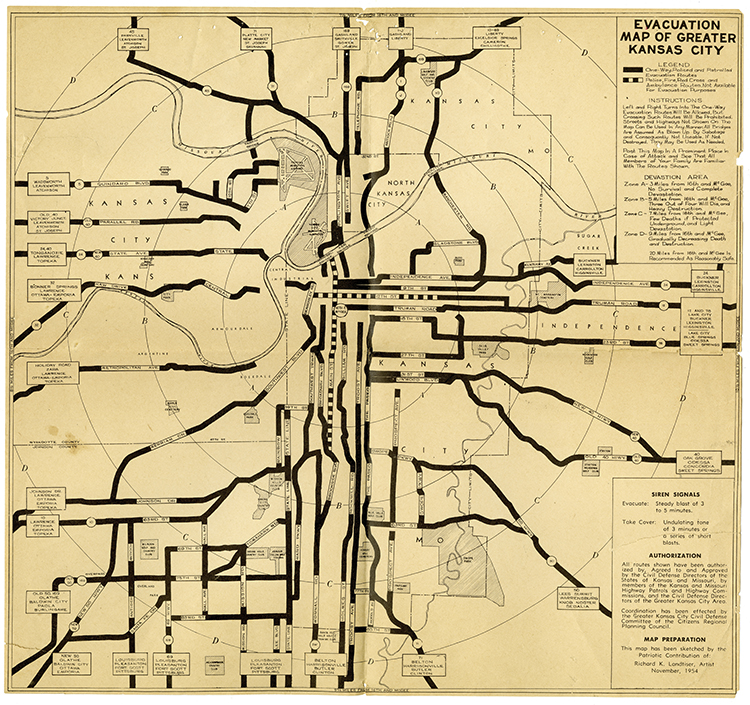

More than 130,000 copies of an evacuation map of the city were printed. In addition to instructions, they displayed four blast zones with damage and survivability estimates radiating outward from 16th and McGee streets in the heart of downtown. Planners hoped that one-way evacuation routes could get downtown residents and workers about 15 miles away in 45 minutes. Their map suggested that 20 miles from ground zero was “reasonably safe.”

The maps were widely distributed in schools, hospitals, city offices, and fire and police stations in preparation for Operation Scamper, an area-wide nuclear attack drill held November 7, 1954. At 1:30 p.m., three-minute-long siren blasts announced the beginning of the drill. Some 2,000 civil defense workers and first responders sprang into action.

Police officers handed out information about the drill to Sunday drivers along evacuation routes and Civilian Air Patrol planes dropped leaflets from the sky. Hospitals in Shawnee, Olathe, and Stanley, Kansas, provided care to Boy and Girl Scouts posing as disaster victims. Command centers in in suburban areas coordinated with Thrasher’s civil defense office inside police radio headquarters at 27th Street and Van Brunt Boulevard.

Complications were built into the plan. Emergency personnel and supplies had to be redirected when their original destinations were “destroyed” in the mock attack. Likewise, “damaged” roads determined to be impassable were closed and hypothetical traffic diverted.

At 2:15 p.m., a last-chance siren was sounded to alert anyone remaining in the blast zone to immediately take cover below ground. Civil defense officials advised: “Lie down against the nearest wall, cover your face with your arms, and leave the rest to providence.”

Lastly, a controlled blast simulating a Soviet hydrogen bomb was detonated along the Missouri River just east of the Armour-Swift-Burlington (ASB) Bridge at 2:30 p.m. The explosion produced a mushroom cloud that rose about 2,000 feet above the riverbank.

A study later determined that the 15-mph northwest wind that afternoon would have spread nuclear fallout across North Kansas City, portions of Clay and Platte counties, and Leavenworth that rendered efforts from those areas futile. Thrasher declared Operation Scamper a complete success. Kansas City was ready.

As atomic weapons and the means to deliver them inside the United States and Soviet Union advanced over the years, the possibility of fleeing a blast zone before a strike diminished. In 1960, Kansas City Mayor H. Roe Bartle suggested that it would be wiser to seek shelter rather than flee the city in the event of nuclear war.

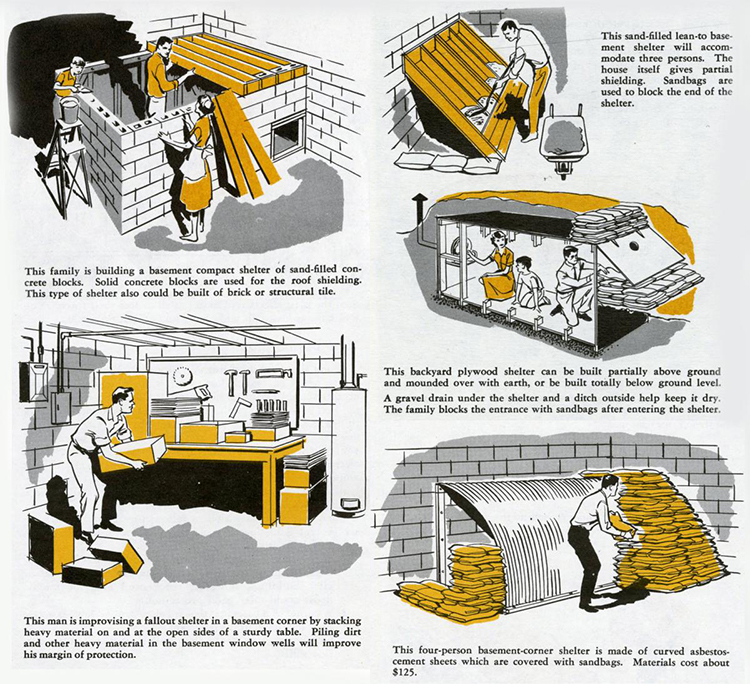

By the early 1960s, homeowners began building backyard and basement fallout shelters and homebuilders began offering them as attractive add-ons. The local chapter of the American Institute of Decorators promoted the use of fallout shelters as family rec rooms to justify the expense.

Construction of new public and private-business buildings during the urban renewal years reflected the new reality. Some projects that received federal funding were required to incorporate fallout shelters into their designs.

The days of duck and cover had returned.

The Federal Civil Defense Administration was reorganized over the years and eventually was replaced by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Today, Kansas City’s Office of Emergency Management plans the city’s response to various disaster scenarios, including nuclear war.

Fallout shelters, once thought of as quaint relics of the Cold War years, are now making a comeback. In a 2018 review of Kansas City’s nuclear attack readiness, The Star interviewed the operators of Defcon Underground Manufacturing, local fabricators of readymade steel shelters built to withstand “anything but a direct hit.”

Like those built in the ‘60s, they can easily be appointed and used as rec rooms.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.