Racing Into Scandalous Cycling History with KCQ

Chain lubed? Helmet on? All right, then, let’s ride.

Reader Mike McGrew wrote to KCQ and asked, “Has there ever been a velodrome constructed in Kansas City? I understand there was a nationwide wave of competitive cycling races in the late 19th and early 20th century.”

Here’s what we found:

There was at least one bicycle racetrack – known as a velodrome – constructed in Kansas City during the great Gilded Age cycling craze. Its story contains all the elements that made cycling a controversial activity in the late-19th century: out-of-town promoters, promises of quick money, gambling at the track, and conflicts between the Saturday night party crowd and Sunday faithful.

Kansas City’s infamous velodrome did not last a full year, its downfall entailing an unexpected twist.

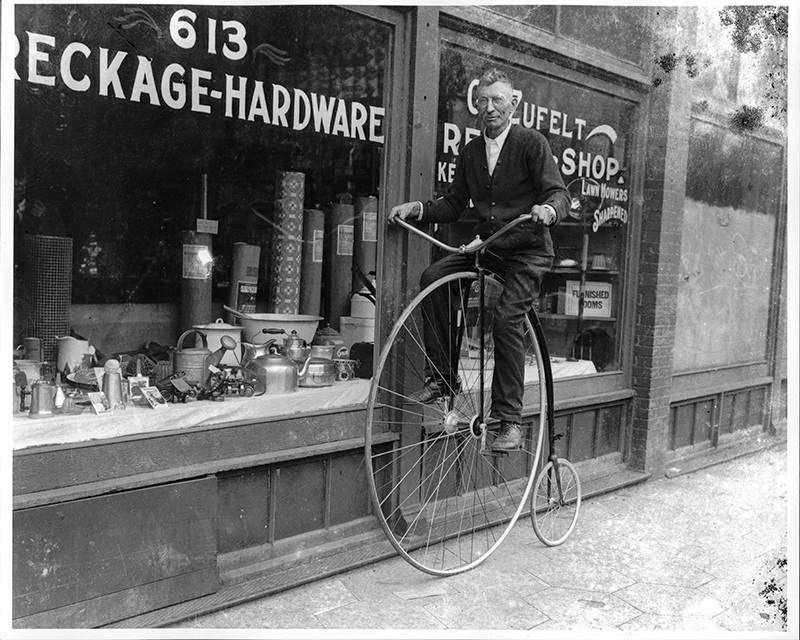

Though bicycles are part of most childhoods today, the two-wheeled machines were a source of some contention in the 1890s. The iconic “high wheel” bicycle, with its enormous front wheel, had become a sensation in the 1880s. But the design was unstable and dangerous, especially for women, who typically wore dresses that could get caught up in the turning wheel.

That changed with the invention of the “safety bicycle,” with its equally sized wheels and a space that could accommodate dresses. But what women gained in the freedom of movement came at the cost of social disruption. Bicycles meant that young people could move throughout the city without adult oversight. It was a concern that would arise again in the 1950s, when the widespread accessibility of automobiles sparked fears about teenage mobility and independence.

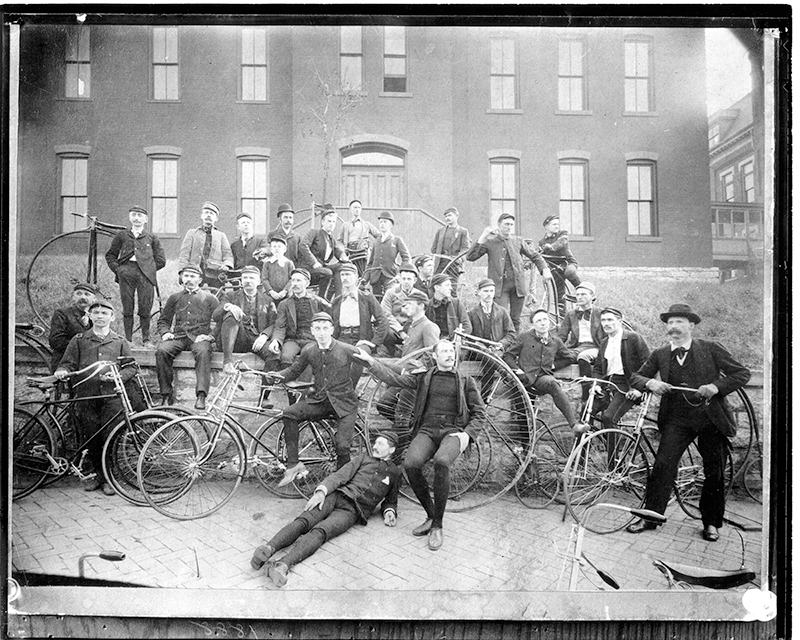

Older generations perceived the bicycle as disruptive technology. Organized races were downright scandalous. Amid that, Jack Prince, described by The Star as a “veteran cycling promoter,” came to Kansas City in April 1899 to revive interest in building an elevated bicycle racetrack known as a velodrome. He created the Kansas City Velodrome Company and sold stock to raise capital for the new venture.

Prince’s ambitious plan involved the creation of a cycling circuit – basically a professional cycling tour – that would move from city to city in the Midwest. Stops would include St. Louis, Chicago, Omaha, and Kansas City, with individual riders racing for cash prizes under bright lights in front of screaming fans. Like any racing promotion, gambling was part of the appeal, even if it was soft-pedaled to avoid further alienating concerned citizens.

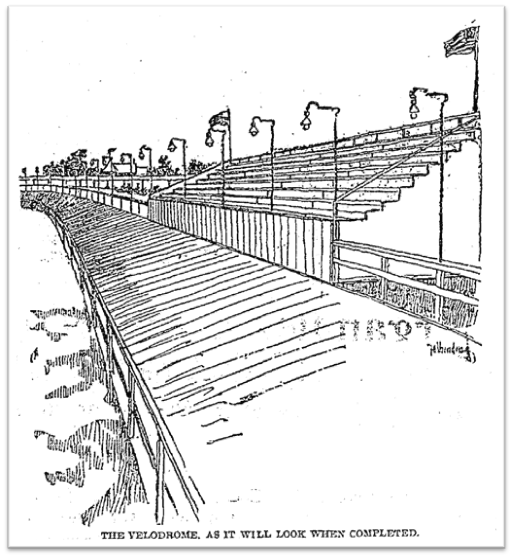

With support from enthusiasts and cycling clubs, Prince opened his velodrome at the northeast corner of 15th Street and Troost Avenue in June 1899. The elevated oval track was banked so racers could gain speed but still make it through the turns. Prince’s promotion drew consistent crowds, and electric lights allowed the action to continue past sundown.

The velodrome pushed gender boundaries with heated women’s competition. One August race featured Carrie Olsen of Minneapolis, Mollie La Tour of St. Louis, and international star Amélie Le Gall – aka Mademoiselle Lisette or “the French Demon.” The contest went down to the wire. Olsen ended the night with a slim lead after an hour and a half of racing, closely followed by Mme. Lisette. After setting the pace for the first several miles, La Tour “fell from her wheel in a faint” after the race and “remained in a comatose condition for nearly half an hour.” Cycling at the velodrome was exciting and dangerous.

But while the velodrome pleased cycling (and gambling) enthusiasts, the racetrack alienated religious and social conservatives. Most incensed were parishioners of the neighboring Dundee Methodist Episcopal Church. In September 1899, backed by Alderman P.S. Brown, they proposed a city ordinance stipulating “that any person who shall build or maintain any bicycle track or velodrome within 300 feet of a church shall be subject to a fine of not less than $100. The fine can be repeated every day until the velodrome has been moved.”

Church members complained that the races disturbed evening prayer meetings and Sunday services. A $100 daily fine in 1899 was the equivalent of $3,089 in 2020. After consideration by the police committee and some revisions, the ordinance passed on September 26, 1899. The Star reported that “The Velodrome is Doomed.”

But this win for Kansas City’s moral crusaders turned out to be unnecessary. Market forces intervened. Prospects for open-air racing in the fall were uncertain, the Velodrome Company tried without success to find a buyer for its distressed property, and creditors foreclosed on the mortgage a week before the restrictive ordinance was approved.

Salvage rights to the velodrome – which had cost $2,500 to build – were sold to the Bruce Lumber Company, which dismantled the racetrack on September 28 for the $1,600 worth of lumber it contained.

Resources:

- The Kansas City Star

- Gilles, Roger. Women on the Move: The Forgotten Era of Women’s Bicycle Racing. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2018.

- Smithsonian Insider: https://insider.si.edu/2018/05/how-the-19th-century-bicycle-craze-empowered-women-and-changed-fashion/