Pleasure Boating on the Blue River? KCQ Navigates This Interesting History

At the turn of the 20th century, Kansas Citians seeking respite from urban life had only to travel a short distance east to enjoy camping, floating, and fishing at a popular recreational destination, the Blue River.

Yes, that Blue River – the now muddy, mostly forgotten waterway that winds through rural, suburban, and industrial areas of Kansas City before emptying into the Missouri River in eastern Jackson County.

A reader had seen images from the early 1900s of cabins and houseboats lining the Blue River near East Truman Road, or 15th Street. The area is now a manufacturing district, and he found it hard believe it once attracted crowds of boaters and vacationers.

He asked “What’s Your KCQ?,” a partnership between The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library: What’s the story?

It is true that the Blue River was once a haven for pleasure boating and other outdoor pursuits. Despite ambitions to make it one of the most scenic waterways in the country, flood control and pollution ultimately led to its demise as a recreational stream.

The Blue River got its name from the onetime blue waters flowing from its headwaters in Johnson County, Kansas, northeast to the Missouri River. It was identified as Blue Water River when the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the tributary in 1804. It has also been commonly referred to as Big Blue or simply the Blue.

During Kansas City’s economic boom of the 1880s, investors began purchasing land just east of the city limits in the Blue River valley. The railroads brought manufacturing, and the industrial towns of Centropolis, Manchester, Sheffield, and Leeds were established. The Blue River not only had the potential for commercial traffic, but also provided swimming, fishing, and other outdoor recreation for the residents of these emerging communities.

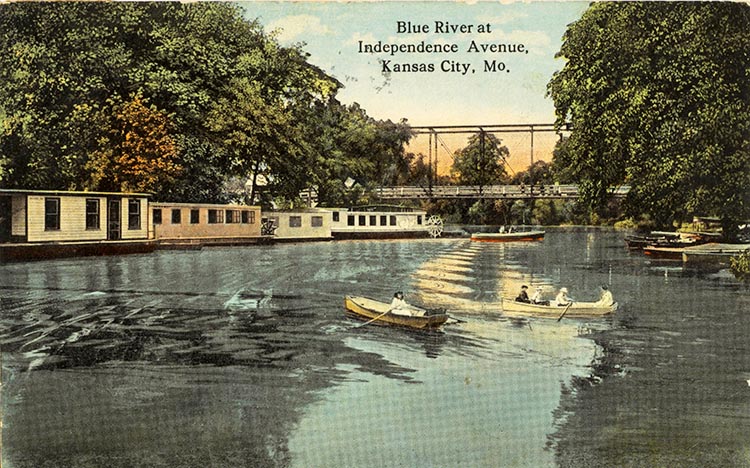

It was a short ride by streetcar, automobile, or wagon for Kansas Citians to enjoy the serenity of the Blue River’s wooded banks and picturesque scenery. Boating and fishing were popular activities. The spring and summer months also attracted swimmers, campers, and picnickers.

BOATING ON THE BLUE

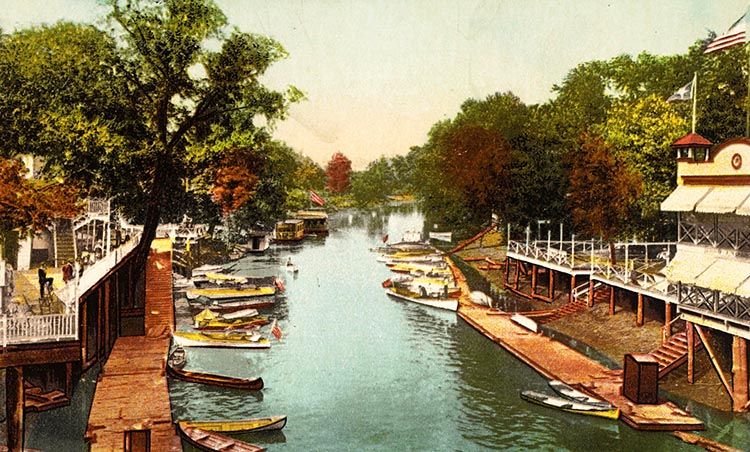

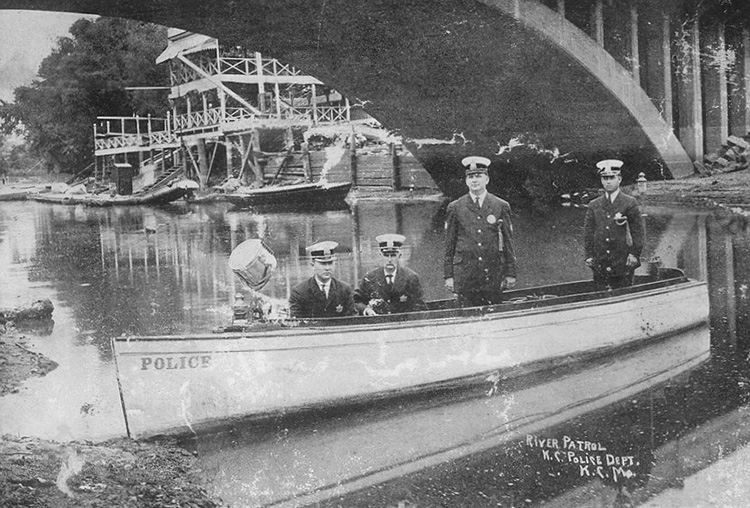

By the early 1900s, numerous boat launch and rental services catered to the increasing number of recreationists. Dozens of cabins and houseboats dotted the banks of the Blue. Much of the boat traffic was concentrated near Independence Avenue, 12th Street, and 15th Street, the primary east-west arteries used to reach the river.

In a time when travel was prohibitive for most Kansas Citians, the Blue was a convenient and affordable getaway. It was unnecessary to travel to the Ozarks to float, fish, and swim when these leisure activities could be enjoyed much closer to home.

Circuit Court Judge Jules Guinotte, an avid boater who operated a launch and rental service, expressed this sentiment in a 1908 Kansas City Star interview. “I would rather spend my vacation on the Blue and Missouri than go to the ‘swell’ summer resorts,” he said. “At the hotels a person has to pay a lot of money for questionable food and cramped accommodations. … Here on the Blue I can have what I want and the way I want it, and I don’t have to spend a fortune to get it, either.”

A community of river dwellers spent the warm weather months living in cottages and houseboats. Some diehards even swore off city life (and city taxes) altogether, choosing to reside there year-round.

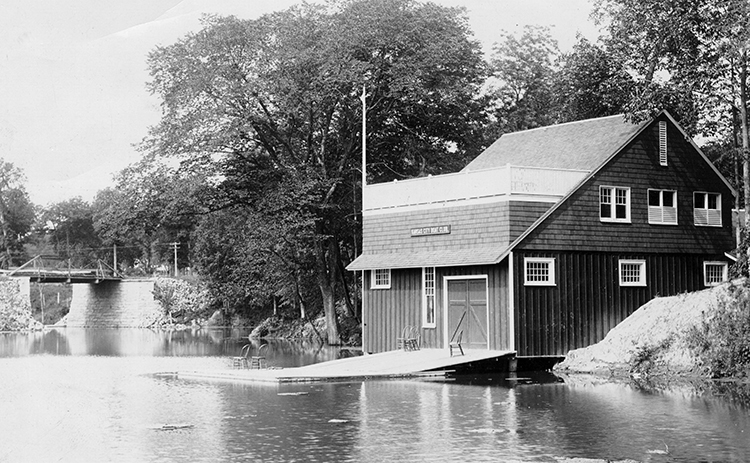

Boating clubs flourished during this period. Two canoe clubs and a women’s boating club regularly paddled the Blue. The Kansas City Yacht Club formed in 1907 with Judge Guinotte as its first president. The group held annual regattas, drawing hundreds of spectators, and led projects to remove trees and other snags from the channel to make it safer for boat travel.

By 1908 there were 65 launches, four boathouses, and fleets of rental craft operating on the Blue. But as river recreation was booming, there were elements, both natural and manmade, threatening the future of the river as a popular outdoor destination.

PRESERVING THE BLUE

Low water was frequently a hindrance to recreational boating on the Blue. Backwater from the Missouri River created deep, slow-moving flows from the mouth upstream to Leeds. This made for ideal float conditions and created depths sufficient for motorized craft. But when the Mighty Mo was running low, much of the Blue was unnavigable.

Proponents of the Blue River also feared that industrial expansion in the valley would cause irreparable harm to the natural surroundings. The wastewater flowing into Turkey Creek and the Kansas River on the city’s west side was a warning of what could happen if steps were not taken to curb manufacturing and contamination.

In 1912, the Board of Park Commissioners drew up an ambitious plan to address these concerns. The Blue River valley would be protected from further encroachment by incorporating it as part of the park system.

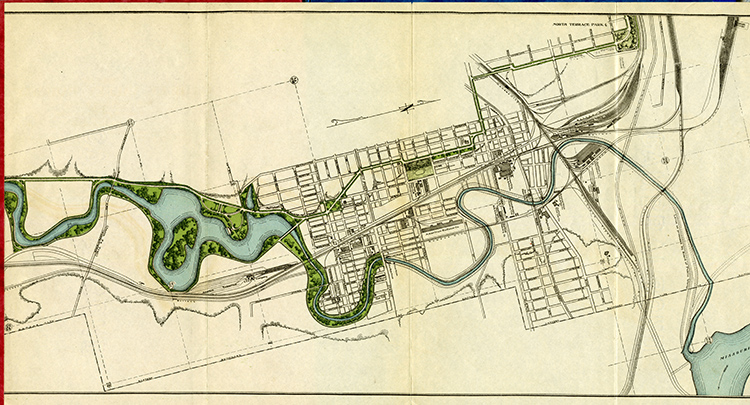

Published as A Special Report for the Blue Valley Parkway, Kansas City, Missouri, the plan called for the acquisition of river frontage from 13th Street south to Swope Park and construction of a “pleasure highway” connecting Swope Park at the southern city boundary to North Terrace Park’s eastern terminus at Indian Mound. George E. Kessler, architect of Kansas City’s parks and boulevard system, stressed the urgency in acquiring riverfront lands before the “rapid absorption of these properties for industrial purposes.”

The proposed parkway would further link the city’s parks system and provide a vital north-south corridor through the Blue Valley.

A key component was the construction of a dam at 15th Street, creating a 140-acre lake for recreation and opening 15 miles of boating upstream to Swope Park. The river below the dam would be utilized as a canal for the transportation of industrial freight.

The project aspired to make the Blue River one of the most useful and beautiful waterways in the country, comparable to the Charles River in Boston and the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. It was endorsed by park officials, city engineers, and transportation authorities.

Despite the potential benefit for residents and the parks system, the Blue Valley Parkway proposal failed to get traction in City Hall, largely due to lack of funding for such a massive project.

As predicted, the Blue River became more polluted and fell out of favor with recreationists in the years to follow. In 1920, The Star referred to it as one of the city’s most underutilized assets, describing it as “a stagnant little stream poisoned by sewers, sick with trash and inaccessible along much of its course.”

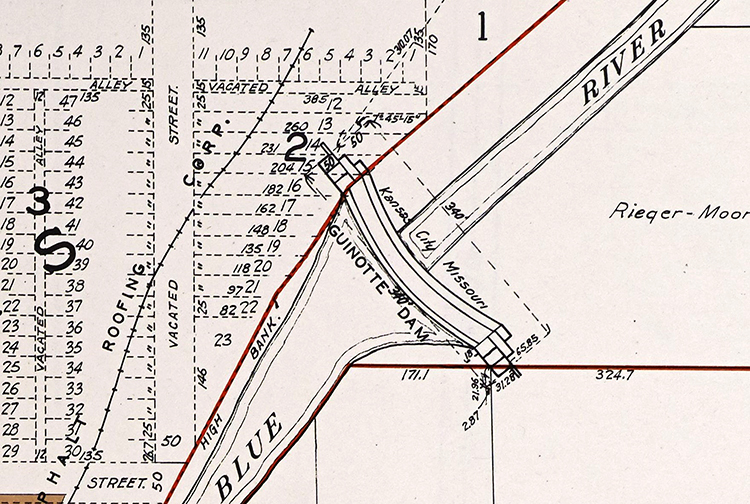

However, progress was made in 1925 with the completion of the Guinotte Dam near 13th Street. Named for the avid Blue River booster, it raised the water level more than 10 feet and opened the way for boating as far south as Swope Park.

Two years later, in 1927, former park board president William C. Scarritt took to the airwaves to advocate for the preservation of the Blue. “It took the Lord something like fifteen million years to create the Blue Valley,” he said in a radio address. “And now, shall we, His children, within a few years, through ignorance and lack of vision, permit that stream and that Valley to be contaminated and that beauty destroyed … merely that we may have misplaced railroad yards and industries and use that river channel as a place for dumping the refuse of factories?”

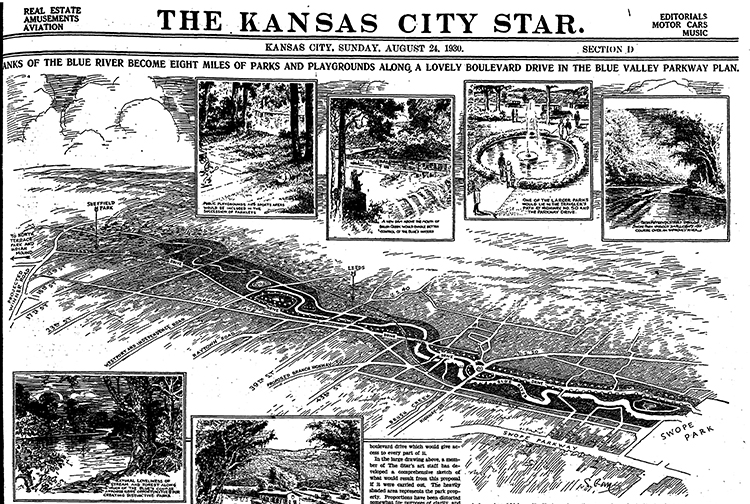

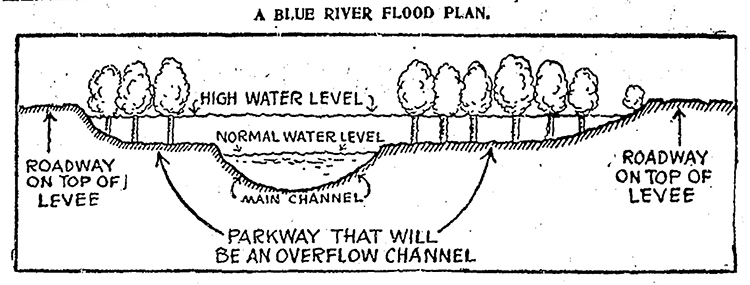

In 1930, the park board again pushed to make the Blue River Parkway a reality. Over $1 million dollars was proposed in a general bond initiative for land acquisition, flood control, and stream beautification. The capstone would be a picturesque, 8-mile boulevard for park visitors who preferred to take in the Blue River’s scenery by automobile rather than boat.

The parkway project was part of Kansas City’s Ten-Year Plan to improve roadways, sewers, parks, and other public works. One million dollars was allocated to begin clearing the Blue’s heavily forested banks. A destructive flash flood in 1928 spurred the need to straighten and widen the river to protect manufacturing interests in the lower Blue Valley from high water.

In 1935, the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) continued the city’s efforts to channelize the stream. More than $8 million over nearly five years was expended on manpower, with an average of 3,000 laborers per day working on the project.

Although it was less of a flood menace, the grand vision of the Blue River as a water park never materialized. City bond money and federal funding dried up – or was misspent, some critics alleged, by a corruptible local government lining the pockets of political boss Tom Pendergast. There would be no bathing beaches, gondola rides, or scenic drives along its banks.

The Star, reporting on the completion of the WPA’s channeling project in 1940, called the promised parkway “a faded civic dream.” The April 28 headline “PLAIN, BUT SAFE” reflected the unfulfilled vision for the Blue River and forecast its future as an underutilized waterway.

RENEWING THE BLUE

The channeling of the Blue River was the beginning of its demise as a recreational stream. Additionally, contamination from sewage and industrial pollutants made the water uninhabitable for most species of fish and dangerous to swimmers.

There would be more floods, the most destructive in 1961 and 1977, and further efforts to keep the Blue from overflowing its banks. Pleasure boating on the once tranquil river became a distant memory.

But the story of the Blue does not end there.

Some 50 years after Kessler and other park officials first proposed a parkway along the Blue River, action was taken to preserve the southern section of the stream and adjacent lands as a public park.

In the 1960s, the Blue River Parkway, stretching from Swope Park southwest to the state line at Kenneth Road, was completed. Under the control of Jackson County Parks and Recreation, the multi-use, 2,255-acre parkway featured several miles of biking and hiking trails, picnic shelters, and other amenities.

Project Blue River Rescue formed in the early 1990s in coordination with the Friends of the Lakeside Nature Center and the Missouri Department of Conservation’s Stream Teams program. Each year, volunteer crews remove tons of tires and trash from the stream to keep it healthy. More recently, the Renew the Blue campaign was launched to clean up and protect the Blue River and restore the surrounding habitat.

While lazy days spent floating its waters and relaxing in summer cottages and houseboats are a thing of the past, the Blue is Kansas City’s river—part of our history—and worth protecting.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.