Mother, May I... Check Out This Book?

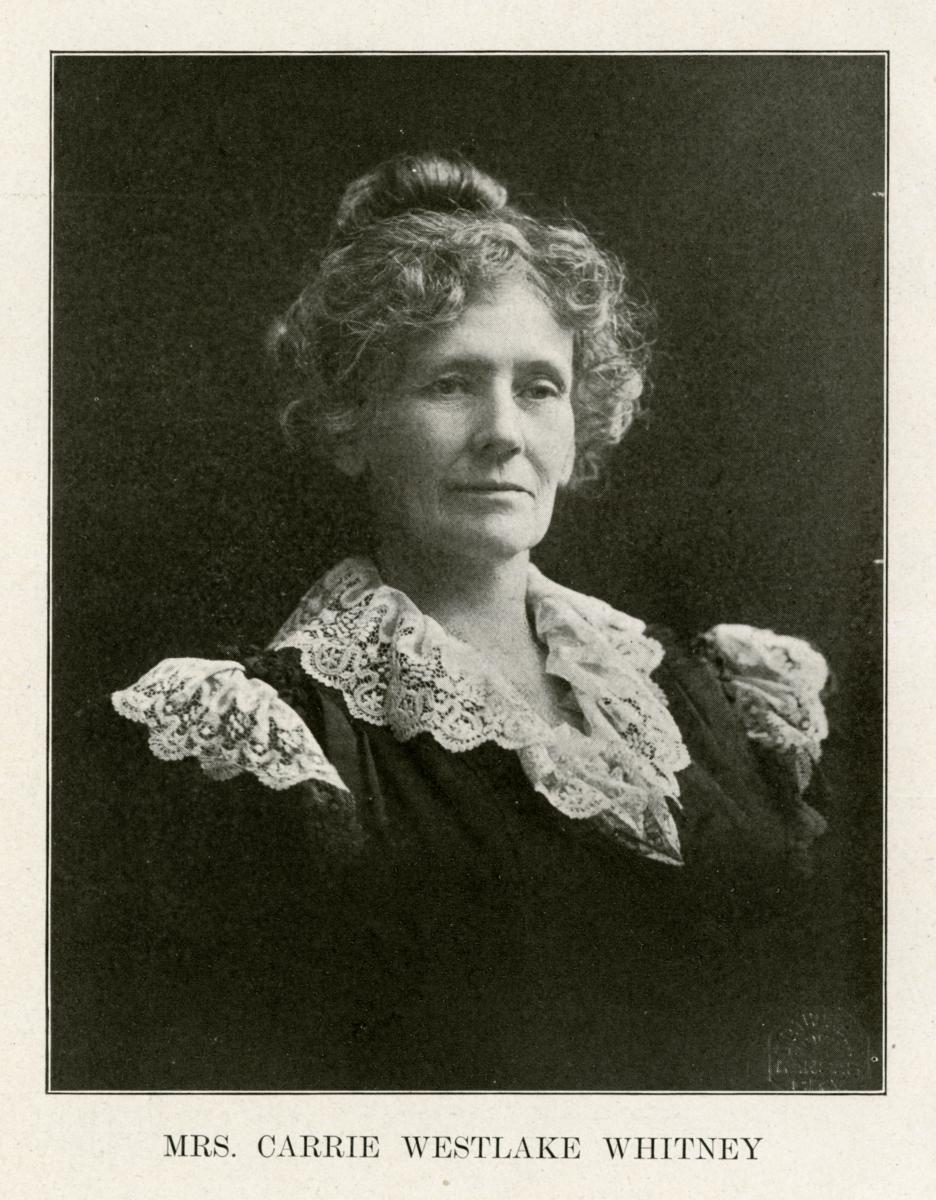

March 16, 1881, marked the first day on the job for 27-year-old Carrie Westlake Whitney as the new Librarian of the Kansas City Public Library – the first paid librarian of the small but growing collection founded in 1873. Mrs. Whitney would make great strides in this role, ushering the Library into the 20th century. After her death on April 8, 1934, the Kansas City Star wrote, “her fine capacity for the office of librarian was quickened by a love of books and an unusual discrimination in literary values.” The Kansas City Times and Kansas City Journal-Post both remembered her as the “’mother’ of Kansas City’s public library system.”

“Mother” seems like a fitting title for Mrs. Whitney, as it usually refers to someone who nurtures and cares for the young (in this case, a fledgling library). During her tenure, she carefully curated a collection she believed would educate and inspire Kansas City as it grew into a modern, industrialized metropolitan area. As she wrote in her first annual report submitted to the Board of Education in 1881:

Great care […] should be exercised in selecting books, otherwise the ends for which a library is founded may be entirely defeated. […] National taste for reading trashy literature, especially among the young, is vitiated. The same desire for knowledge, if properly directed, would have lead [sic] to an appreciation of our best authors, more cultivated tastes and a higher literary standard generally. A nation is elevated only as all the people are capable of passing into higher planes of social and intellectual enjoyment.

Upon starting the job, Mrs. Whitney took control of a collection of about 3,000 volumes located in rented rooms in a building at 546 Main. She immediately began selling subscriptions, tracking patrons’ reading tastes, reorganizing the catalog, and acquiring titles. She gradually eased restrictions on school children using and borrowing books and established a free reading room to encourage access to the collection. Additional staff were hired and operating hours increased. But more resources were needed. Most of her early reports repeat an appeal she wrote in 1883: “We need more room, more money, and more, many more books.”

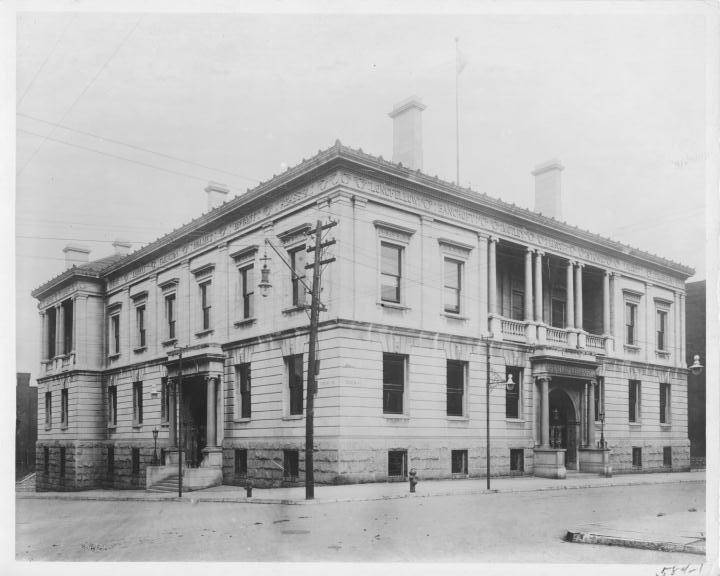

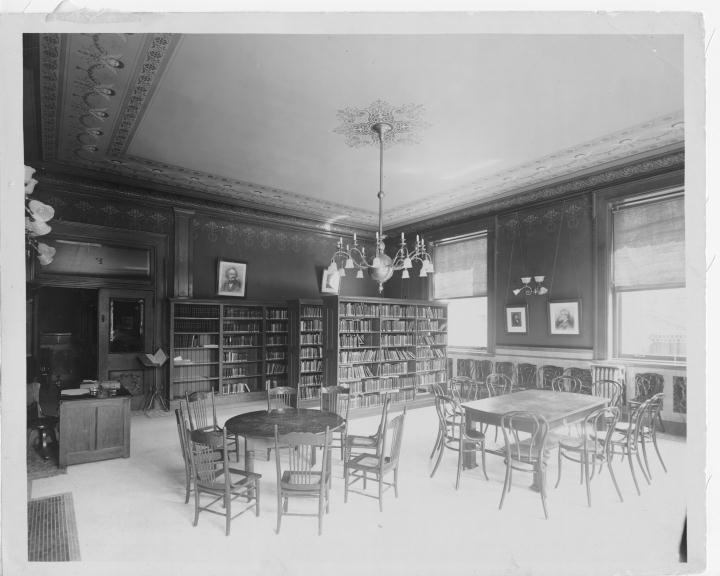

The Library moved into progressively larger spaces in 1884 and 1889, but both filled up quickly. It must have felt like a dream come true for Mrs. Whitney on September 1, 1897, when the brand new, three-story building opened at 9th and Locust. It featured a reading room, ample book stacks, dedicated rooms for children’s and reference collections, art gallery, natural history museum, and public meeting rooms. The collection now numbered ten times more than what Mrs. Whitney had started with. She reported to the Board that it took only three days to move all 30,000 items into the new building by wagon and, “there was no confusion, not even the misplacement of a single book, everything having been previously arranged.”

The next milestone came on January 1, 1898, when subscription fees were eliminated and the Library became free to the public.

Professionally, Mrs. Whitney was busy outside of the building as well. She was an active member of the American Library Association and Missouri Historical Society, and first president of the Missouri Library Association. She also created and copyrighted an index to the magazine Harper’s Weekly, edited a professional newsletter, and found time to write and publish a three-volume, 689-page book titled, Kansas City: Its History and Its People 1808-1908.

Then the wheels came off.

Mrs. Whitney was demoted to Assistant Librarian in July 1910. Exactly why is unknown, but there had been complaints that the rules of the library were too strict, about her judgmental attitude towards certain books (she frequently wrote and spoke about her distaste of popular fiction), and even on the temperature of the building. One patron grumbled in a letter to Board Member Frank Faxon that the windows in the reading room were often opened during the winter, allowing “a freezing current… to sweep through the room which speedily drove all bald-headed and partially bald-headed men out.” (This letter is stored in SC6 Kansas City Public Library Archives and is available for viewing.)

However, the Board of Education’s official stance regarding the change was that it believed that a man would be a better fit for the position of Head Librarian. Two years later, on September 5, 1912, Mrs. Whitney was forced to resign following the Board’s investigation of what the Journal-Post called “friction” between Library employees that was deemed “detrimental to the best interests of the library and the public.”

After her impressive career unceremoniously ended, Mrs. Whitney essentially dropped out of public view. Not much is known about her personal life, though records indicate that she had been married twice in her young adulthood, but neither marriage lasted long. Her obituaries state that she spent the last 40 years of her life living with her “inseparable friend” Miss Frances Bishop, herself a former librarian.

Interestingly, as historian Shirley Christian has noted, it’s appropriate that more personal details about her aren’t available. Mrs. Whitney included a short autobiography in her book, Kansas City: Its History and Its People, ending with, “Mrs. Whitney’s biography is the history of the Kansas City Public Library.”

Proud mothers do like to brag about their kids.

Publications by Carrie Westlake Whitney:

Continue researching Carrie Westlake Whitney using materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

Mrs. Whitney is also featured in the online version of Coloring Kansas City: Women Who Made History, a coloring book honoring just a few of the influential women who have called Kansas City home. Visit the project’s webpage to download the book and learn more!