Lyda Conley: Wyandot Guardian and Lawyer

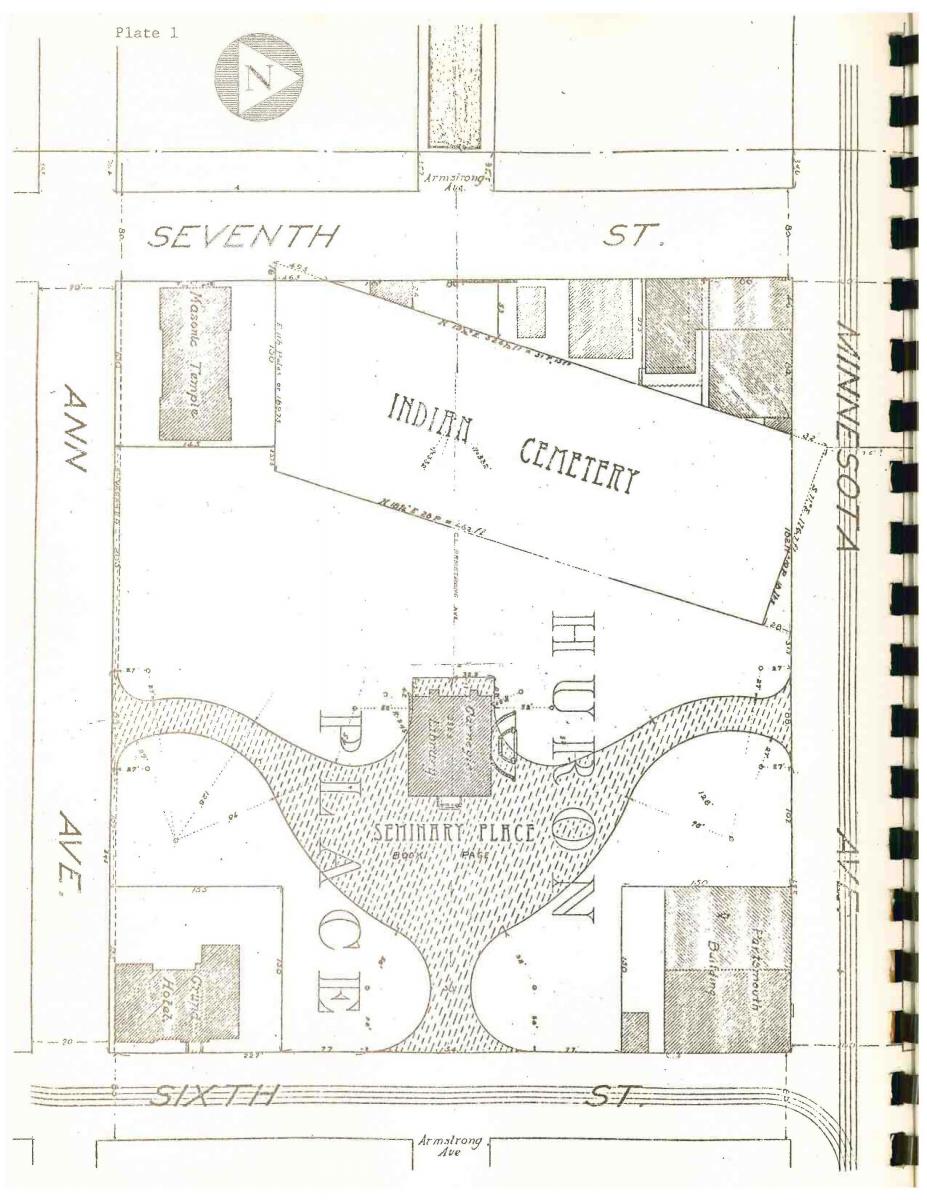

The Wyandotte National Burying Ground in Kansas City, Kansas, also known as Huron Indian Cemetery, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, and was designated a National Historic Landmark late in 2016 thanks to the impassioned and persistent efforts of Eliza “Lyda” Burton Conley and her sisters Ida and Helena. Their lives’ work was protecting this spot of land that had been promised to their Native ancestors by the United States government after they were forcibly removed from their homes.

The land was first used as a burial ground by the Wyandot Indians after they were forced to relocate to the area from Ohio under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The cemetery was given protected status by an 1855 treaty between the U.S. government and the Wyandot tribe. In exchange for the Wyandots giving up tribal status to become U.S. citizens, the treaty provided, among other things, that “the portion now enclosed and used as a public burying-ground, shall be permanently reserved and appropriated for that purpose.”

While some Wyandot members were willing to give up their tribal affiliation, others were not. Those who resisted were placed in an exempt category, and many moved to Oklahoma Indian Territory. The 1855 treaty created long-term complications that were left unaddressed for many years between the federal government, the Wyandot members who had stayed in Kansas, and those who resettled in Oklahoma. Sometime after 1862, the Wyandots who fled to Indian Territory organized a rival council that often opposed the “citizen-Wyandots” who stayed in Kansas. The newly organized Wyandotte Tribe of Oklahoma joined with other tribes in Indian Territory to negotiate a treaty with the government to restore their tribal status while leaving out the Kansas Wyandots.

By the late 1800s, the community surrounding the Wyandotte burial grounds had grown into the city of Kansas City, Kansas. But many residents saw the centralized location of the cemetery as a roadblock to continued commercial progress. The first legal threat to the cemetery came in 1890, when Kansas Senator Preston B. Plumb introduced a resolution to Congress for the cemetery to be removed to another location. The measure languished until 1899, when the cause was revisited by a real estate man, William Connelly, who saw the financial benefits of facilitating a sale of the cemetery. At the time, the Kansas Wyandots had no recognized legal status as a tribe but the Wyandotte Tribe of Oklahoma did. Connelly acquired power of attorney for the Oklahoma Wyandotte tribe and proposed selling the cemetery and distributing the proceeds among the Oklahoma Wyandottes while keeping a cut for himself.

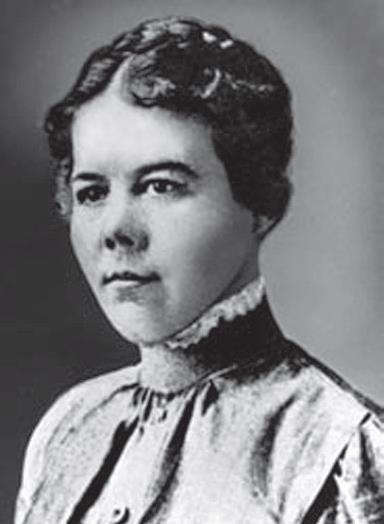

Around the time these battles were being waged, Lyda Conley decided to fight back against the men threatening her ancestors’ burial grounds. She armed herself with the knowledge and power to protect the land by pursuing a law degree. Lyda graduated from the Kansas City School of Law in 1902, was admitted to the Missouri Bar soon after, and the Kansas Bar in 1910. Although Kansas was relatively progressive when it came to women’s legal rights, it was still a rarity for women to practice law. Upon graduation from law school, Lyda managed a caseload along with teaching telegraphy at Spalding Business College.

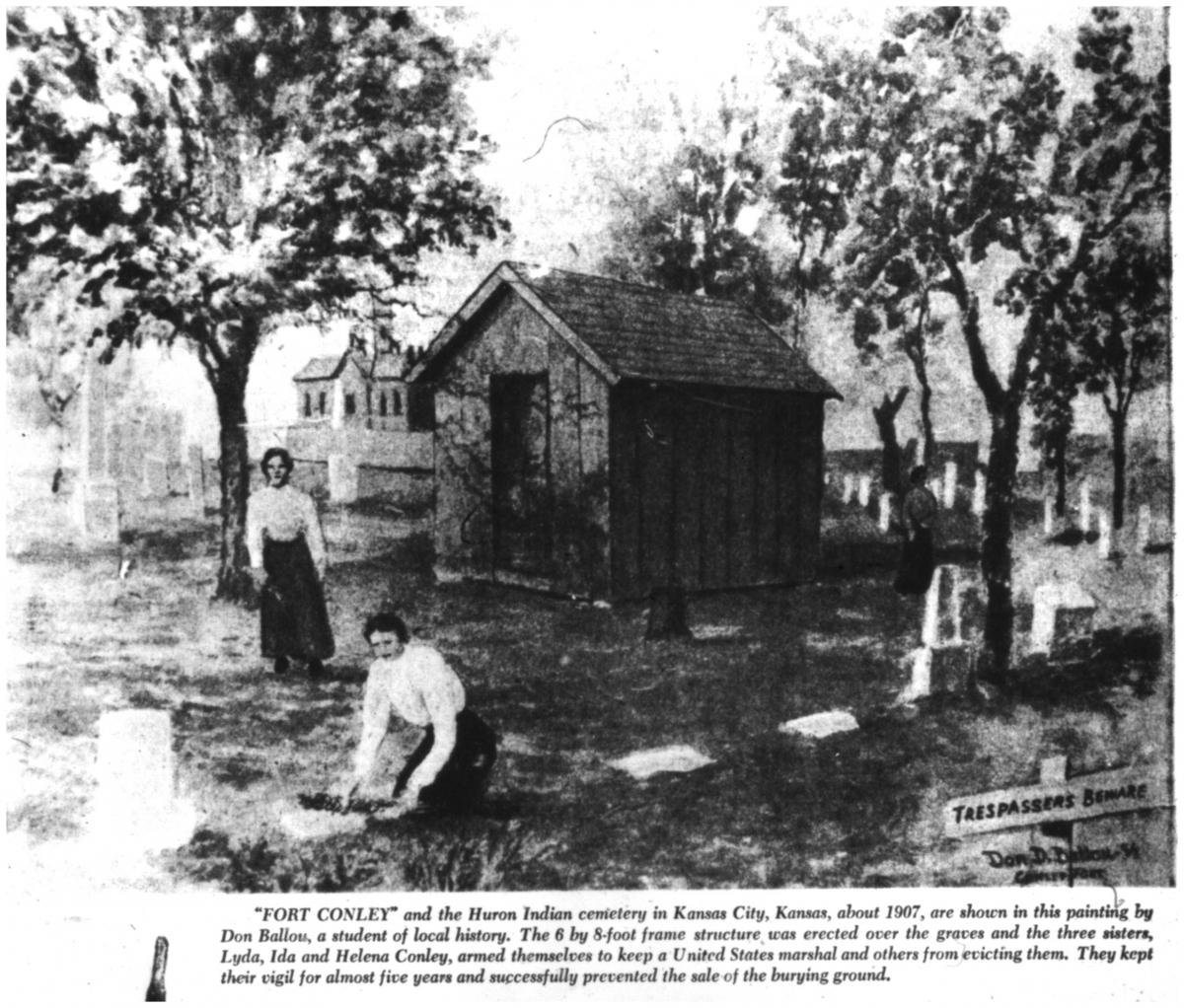

While William Connelly was unsuccessful in his earlier attempts to sell the cemetery, he was able to convince the Secretary of Interior to appoint a commission in 1906 to facilitate the sale of the land. Still building her legal knowledge and credentials, Lyda and her sisters responded to this threat by arming themselves with shotguns and moving into the cemetery. They erected a hut around their mother’s gravesite and threatened anyone who came to disturb the land.

This passionate defense of the cemetery grabbed the attention and support of many of the upper-class white women in Kansas City. Public sentiment began turning against the commission, and it was unable to reach a deal with the city for the sale of the land at that time. But the fight was far from over.

In June 1907, Lyda began the legal battle that would take her to the U.S. Supreme Court in January 1910, making her the first Native woman to argue a case before the highest court in the land. Although the Supreme Court did not rule in Lyda’s favor, accounts of her argument indicate an extremely passionate, intelligent, and creatively complex legal plea for the continued protection of the Wyandotte National Burying Ground.

After Lyda’s loss in court, she and her sisters continued guarding the cemetery despite repeated attempts by authorities to run them out. In 1912, Kansas Senator Charles Curtis intervened and brought a bill before Congress that recommended the cemetery’s designation as a national monument. In 1916, the cemetery received congressional funding for preservation as a historic site and was placed in the care of Haskell Institute, now Haskell Indian Nations University.

Despite this progress, the Conley sisters continued to watch over the cemetery and insure its upkeep be taken with care. They were arrested multiple times for interfering with city officials’ presence in the cemetery, and people reported that Helena was placing curses on those she saw as being disrespectful to the gravesites. After Lyda’s death in 1946, the federal government again attempted to sell the land. But Wyandot descendants and local historians continued Lyda’s battle and in 1971, the cemetery was put on the National Register of Historic Places and in 2016, recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

Lyda Conley’s story is fascinating and unusual for numerous reasons. As a woman of Native American descent living in a time when neither of those designations allowed for full rights under U.S. laws, she accomplished great things and had a significant impact that went far beyond her immediate community. Although she lost her litigation for ancestral burial grounds, Lyda’s enduring commitment to fight for her people and the land that was promised them inspired many in her community who took up her fight after her death.

Lyda Conley is also featured in the online version of Coloring Kansas City: Women Who Made History, a coloring book honoring just a few of the influential women who have called Kansas City home. Visit the project’s webpage to download the book and learn more!

Continue researching Lyda Conley and Huron Cemetery using materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

Vertical File: Cemeteries-Kansas-Huron.

Connelley, William E. “The Wyandots.” Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society, Vol. 6, 17 January 1899.

Gregg, Bill. “Huron Place.” The Historical Journal of Wyandotte County, Vol. 2:10, 2008.

Harrington, Grant W. Historic Spots or Mile Stones in the Progress of Wyandotte County, Kansas. Merriam, KS: Mission Press, 1935.

Worley, Kathryn. “Women Lawyers in and Around Kansas City.” The Westporter, March 2005.

Additional References:

Dayton, Kim. “’Trespassers, Beware!’ Lyda Burton Conley and the Battle for Huron Place Cemetery.” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism Vol. 8:1, 1996. http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1110&context=yjlf (29 March 2018).

United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. “Wyandotte National Burying Ground, Eliza Burton Conley Burial Site.” National Historic Landmark Nomination, https://www.nps.gov/nhl/news/LC/spring2016/WyandotteNationalBuryingGround.pdf (29 March 2018).

Wyandotte Nation. http://www.wyandotte-nation.org/culture/history/ (29 March 2018).