KCQ Taps into the History of an Early Kansas City Beer Garden

On the first weekend of October, thousands of Kansas Citians will raise a glass – or perhaps more fitting, a stein – to celebrate German heritage during KC Oktoberfest at Crown Center. It will be two days of Bavarian-style food, music, and, yes, bier.

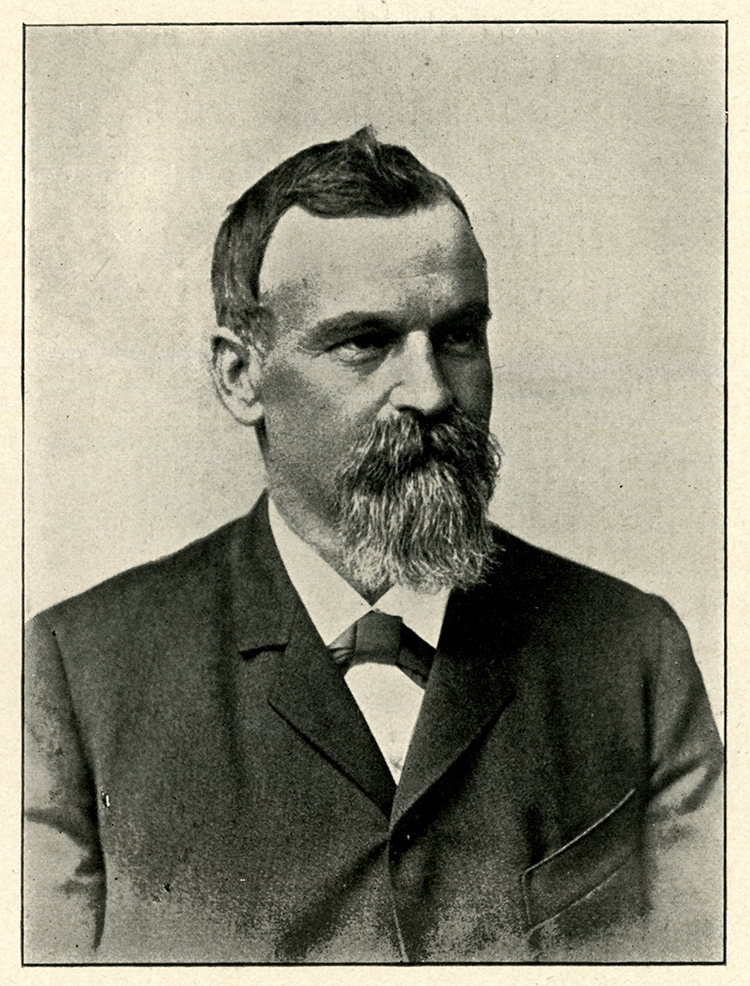

The latest installment of What’s Your KC Q?, a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library, tells the story of German immigrant named Martin Keck who operated a popular beer garden in the 1870s. A century later, the property he developed would become the site of one of the city’s most iconic destinations: Crown Center.

Reader Lori Moore put KCQ on Keck’s trail, asking: “What was originally on the site of the Westin Hotel at the corner of Main and Pershing Road?”

BAKER, FREIGHTER, AND BREWER

Keck learned the baking and milling trade in Wϋrttemberg, Germany, before immigrating to the U.S. at age 19. He arrived in New York in 1855 and made his way to Independence, Missouri, where he was employed by the Judinger Bakery. Keck was among a small population of German merchants and artisans who established roots in the area and prospered from the booming Santa Fe Trail commerce.

By 1860, he had settled in Westport, which had supplanted Independence as the main disembarking point for Santa Fe Trail travelers. During this period, Kansas City and Westport had relatively few German immigrants as their ardent abolitionism clashed with the populace’s largely pro-slavery leanings.

Keck turned from baking to freighting in 1862, forming a business partnership with his friend Charles Raber. They purchased oxen, wagons, and goods, and made more than 20 trips to the Southwest over the next six years.

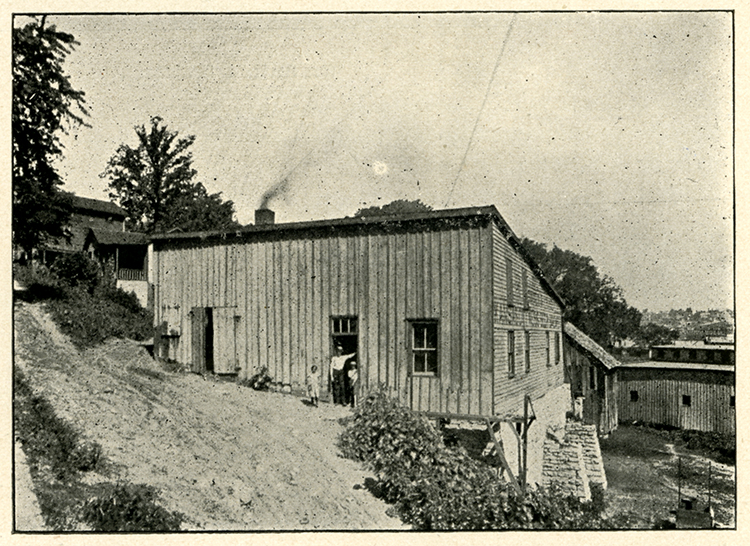

Transporting goods overland by wagon was arduous and often dangerous work, but also lucrative. Using profits from their freighting venture, they invested in a brewery near 24th Street and old Westport Road owned by Keck’s father-in-law, Heinrich Helmreich.

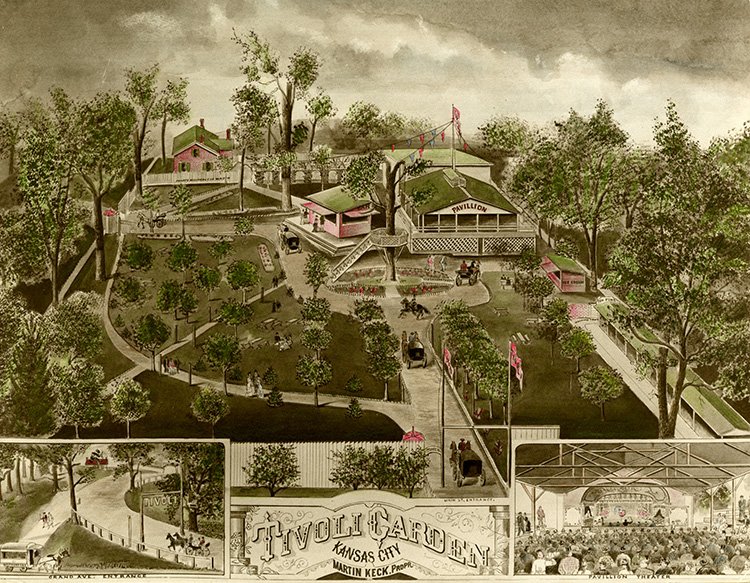

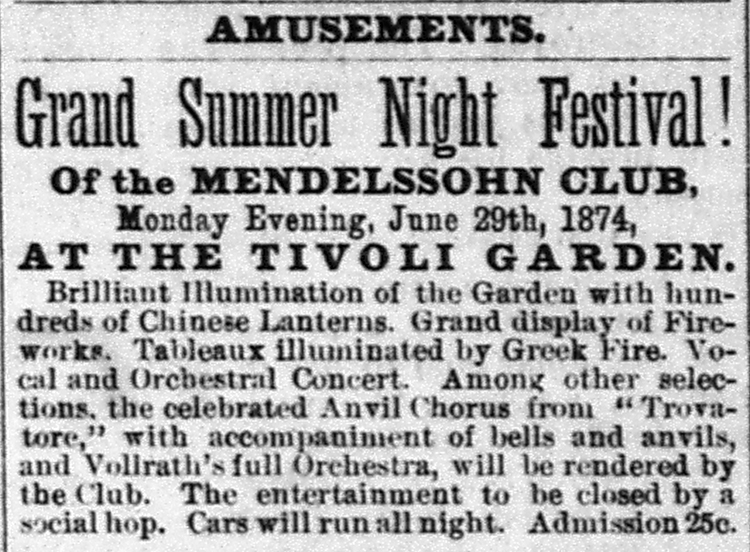

Keck sold his interest in the business in 1870 and built a traditional German biergarten west of the brewery property at 24th and Main streets. He called the venue Tivoli Garden.

Extending north to roughly 23rd Street, the grounds housed a main pavilion and theater, ten pin bowling alley, beer bar, and ice cream stand. Upon entering the 6-acre estate, visitors would gaze upon stately trees and manicured gardens, pathways, and picnic areas. The Keck home was located on the southeast corner of the property.

Keck’s beer garden was the first located south of 12th Street and was a popular gathering place for the city’s German residents, especially for Sunday afternoon picnics and concerts. Tivoli Garden became so closely associated with local Germanism that the bluff it sat upon was called Dutch Hill.

A CITY VIEW

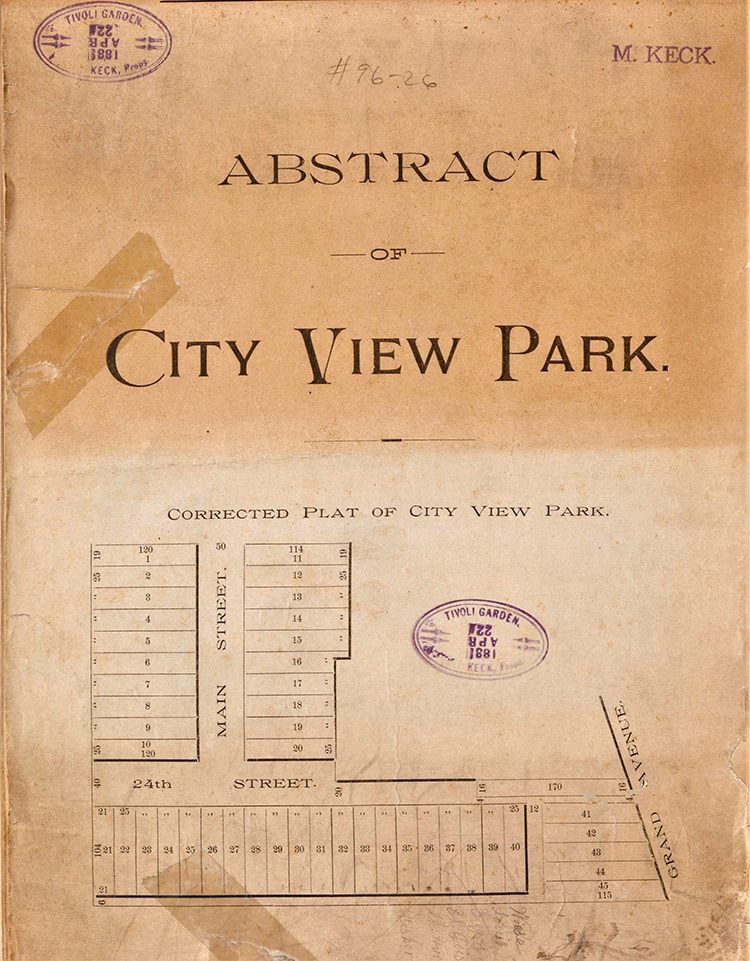

The beer flowed freely until around 1879, when a new ordinance prohibited the sale of alcohol on Sundays. Soon after, Keck began subdividing and selling lots of the Tivoli Garden property, which he platted as City View Park. As the name suggests, the development was perched on a hilltop with commanding views of downtown.

An Abstract of City View Park held in the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections shows the property previously being owned by several prominent citizens. Westport founder John Calvin McCoy purchased the land from the U.S. government in 1835. It changed hands two more times before Nathan Scarritt and Edward Peery, both Methodist ministers and missionaries, acquired the property in 1857 as part of Scarritt and Peery’s Subdivision.

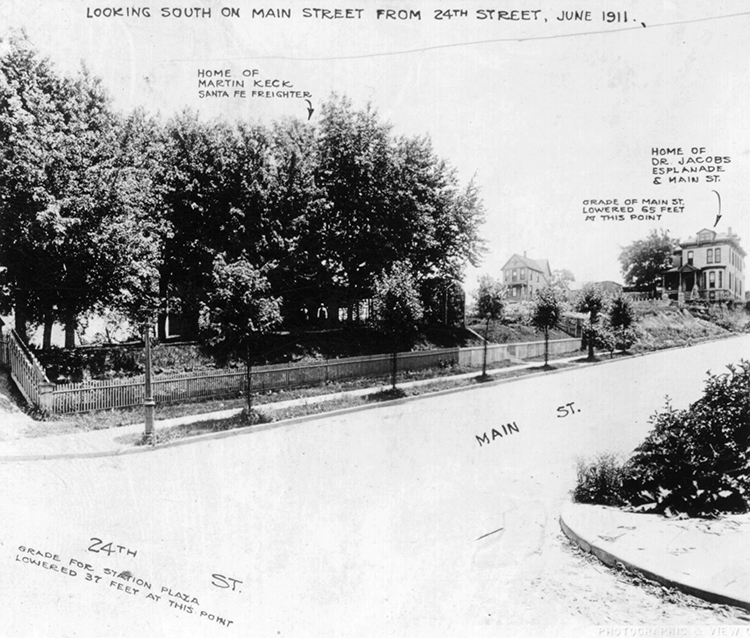

Keck retained the family homestead in City View Park and lived there until his death in 1908.

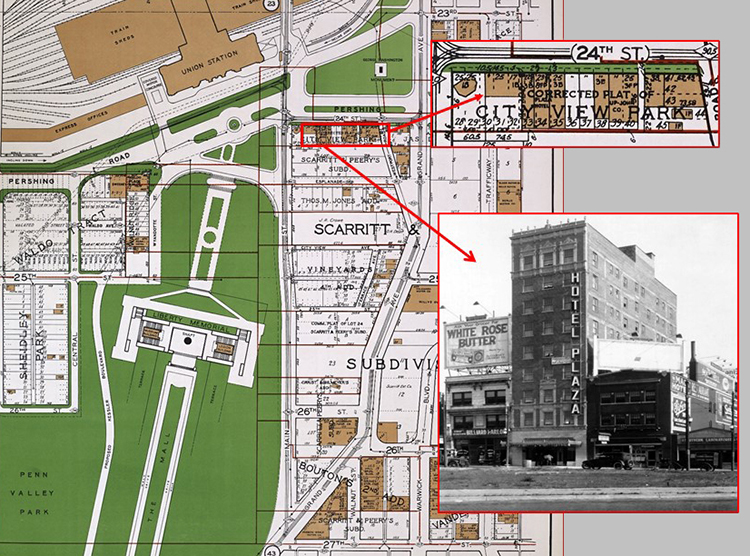

When a site just northwest of the Keck residence was chosen for the new Union Station, the property fronting 24th and Main streets became desired real estate. Keck’s widow, Mary, leased it to the Plaza Leasehold & Investment Company for 99 years, for just over $7,500 annually.

Union Station’s construction precipitated major changes to the roadways and topography of City View Park and the surrounding area. Work began in 1910 to carve through the bluffs from 23rd and Main south to 27th Street. The former Tivoli Garden site was graded down 44 feet, and the widening and paving of roads was completed ahead of the station’s 1914 grand opening.

A decade later, the area had been further transformed. The Liberty Memorial monument towered to the south of Union Station. The 9-story Hotel Plaza was built on the Keck property fronting 24th Street, which had been renamed Pershing Road for U.S. general John J. Pershing. Across from the hotel was Washington Square Park, honoring another revered military general and first U.S. president.

FROM URBAN EYESORE TO CROWN JEWEL

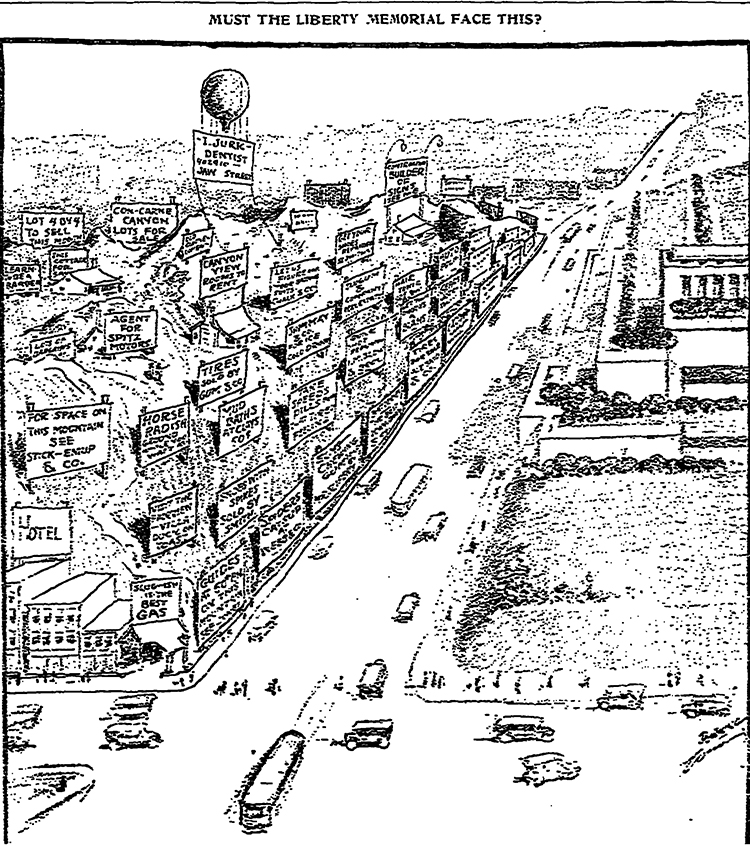

One of the first landmarks visitors encountered when arriving to Union Station was the striking Liberty Memorial monument in Penn Valley Park. But the rugged hillside east of the park was far from picturesque. Dozens of garish billboards, stretching from 24th to 27th streets on the east side of Main, advertised everything from paint, batteries, and tires to cigars and liquor. The commercialized landscape was dubbed Signboard Hill.

A 1923 Kansas City Star article identified 77 billboards of various sizes, including 17 facing the memorial site and more than half a dozen at the 24th and Main Street intersection pointing northwest, “as if fighting to be the first to shout at persons arriving at the union station.”

The panorama of signage along the limestone bluffs drew the ire of the Memorial Site Protective Association, as well as many city leaders and citizens. There was public outcry over Signboard Hill as an “eyesore,” “blot,” and “monument of ugliness,” with some advocating for the city to acquire the property through condemnation as it had done previously to develop the park system.

In 1925, Kansas City voters failed to pass a much-publicized bond ordinance that would have generated $2 million for acquisition of the land.

In subsequent decades, the city considered numerous proposals to develop Signboard Hill. A civic center, courthouse, World War II memorial, and stadium were a few of many projects that never gained sufficient traction to move forward.

But that changed in the late 1960s when Hallmark Cards, Inc. – founded by Joyce Hall and then headed by his son, Don – began developing Hall’s Crown Center, a mixed-use retail, residential, and office complex.

Hallmark had been headquartered at 26th Street and Grand Avenue since 1922, quietly acquiring properties in the vicinity with an eye on redeveloping unsightly Signboard Hill.

The Crown Center plan was approved by the city in 1967, and ground broke on the $200-million project the following year. By 1973, some 400,000 tons of rock and shale had been removed and the hill was transformed into an 85-acre complex of shops, restaurants, and offices.

The 20-story Crown Center Hotel at Main Street and Pershing Road, operated by Western International Hotels, became the Westin Hotel in 1981.

Crown Center remains a popular shopping and entertainment destination to this day, attracting 5 million visitors per year.

And to think, it all started with a German beer garden. Prost!

NOTE

Special thanks to Doris Ganser of Transimpex Translation Services and Maxi Moody at the KCPL’s L.H. Bluford Branch for their assistance with translating biographical information about Keck, Helmreich, and Raber found in Kansas City und fein Deutschthum im 19. Jahrhundert.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.