KCQ spotlights Nikoles Aleshi and his ‘Virtuana Lengueje Sistem’

National Immigrants Day on October 28 celebrates the U.S. as a melting pot of diverse cultures, customs, and ethnicities and honors the perseverance and contributions of those who sought opportunity in America.

Among them was Nikoles Aleshi, a poor Italian immigrant who built a successful grocery business in Kansas City at the turn of the 20th century. But he had grander aspirations of creating a new national language that would be easier for non-English speakers to learn. His story fascinated a local reader who asked What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between the Kansas City Public Library and The Kansas City Star, to investigate it further.

A descendant of Aleshi donated his papers to the Library’s Missouri Valley Special Collections in 1971. These records, compiled as the Nikoles Aleshi Virtuana Language Collection, provide insight into his crusade to create a simpler language system.

Nicolo Alesci was born in Sicily, Italy, in 1863. The youngest of five children, he began picking olives at age 5, earning 2 cents per day, to help his family make a living.

He was among thousands of Italians – fueled by widespread poverty and strife in their home country — who immigrated to the U.S. in the 1880s. The 24-year-old Aleshi arrived in New York in 1886 and made his way to New Orleans, where he worked at a sugarcane plantation and later for the railroad.

In 1894, he married Josephine “Josie” Asta in Jackson County, Missouri, and the couple settled in the Little Italy neighborhood on Kansas City’s north side. Aleshi ran a grocery, dairy, and olive oil import business from a storefront at 312 Holmes St. and saved enough to purchase a small dairy farm at 66th and Belinder in present-day Mission Hills, Kansas. According to a written account by his granddaughter, Josephine Cisetti, he was one of the first dairymen in the city to deliver milk door to door to customers.

Although Aleshi loved America, like many other immigrants, he struggled with the idiosyncrasies of the English language. He called it “the most hazardous national problem” — one he became obsessed with solving.

A conversation with a group of men about the correct pronunciation of his last name compelled Aleshi to compile a dictionary of common Italian words with corresponding English pronunciations and meanings. Upon examining the completed table, he had a vision of a new language system derived from Italian pronunciation and English grammar.

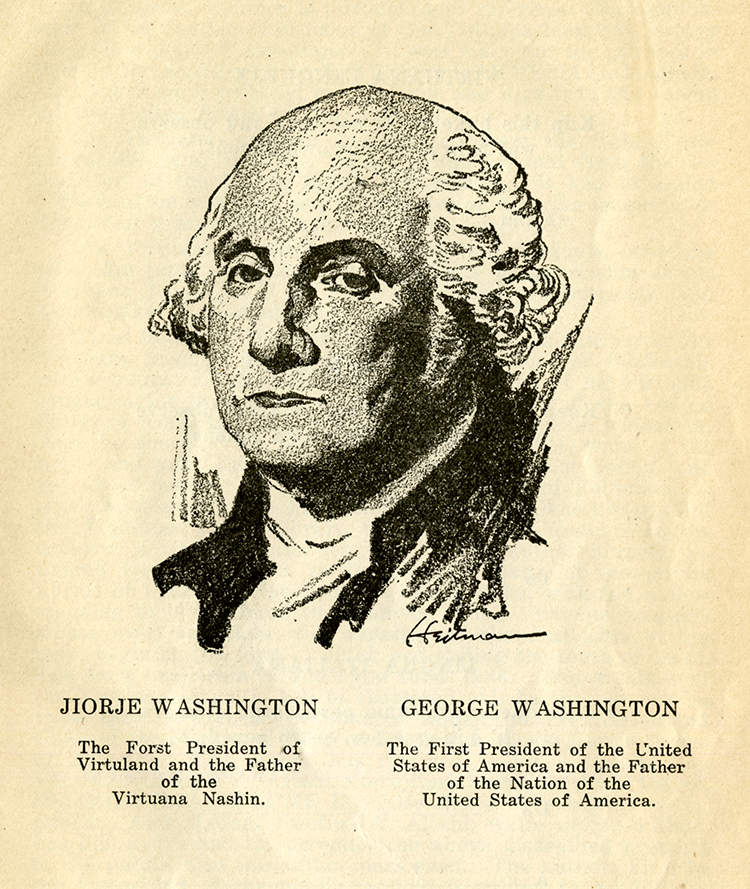

Aleshi completed an initial draft of his Niu Speling Eksperiment in 1906 and spent the next three years refining it into a phonetics-based language he called Virtuana

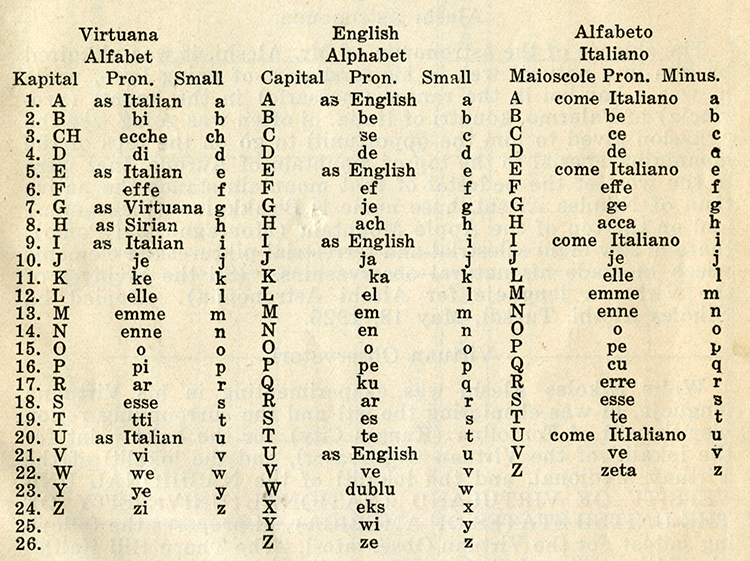

The Virtuana “alfabet” mirrored its English counterpart but with only 24 letters — Q and X being omitted — and each letter having a singular pronunciation. Silent letters and other pitfalls inherent in learning English spelling and pronunciation were eliminated.

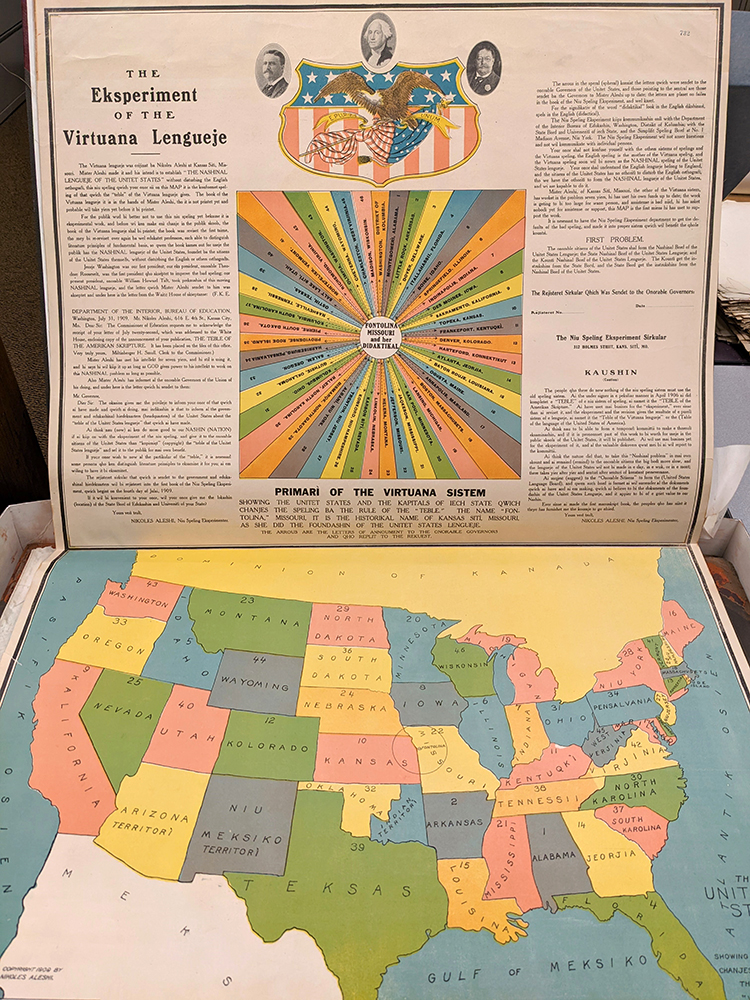

The Italian grocer who lacked any formal education had grand ambitions of Virtuana’s widespread usage and adoption as the national language. He began referring to the United States as “Virtuland,” signifying virtue, and Kansas City as “Fontolina,” the fountain from which his new language would flow.

He changed the spelling of his name from Nicholas Alesci to “Nikoles Aleshi,” and his business to the “Iteli Deiri Kompani.” His storefront windows were billboards for Virtuana, advertising “Fensi Groseri” and “Proper Lengueje Pronounsiashin.”

Virtuana’s “Nashinal Universiti” and “Nie Speling Skool” were headquartered in a small room in the back of the Aleshi grocery store. Professor Aleshi (a title he bestowed himself) was instructor and his wife and their eight children the first students.

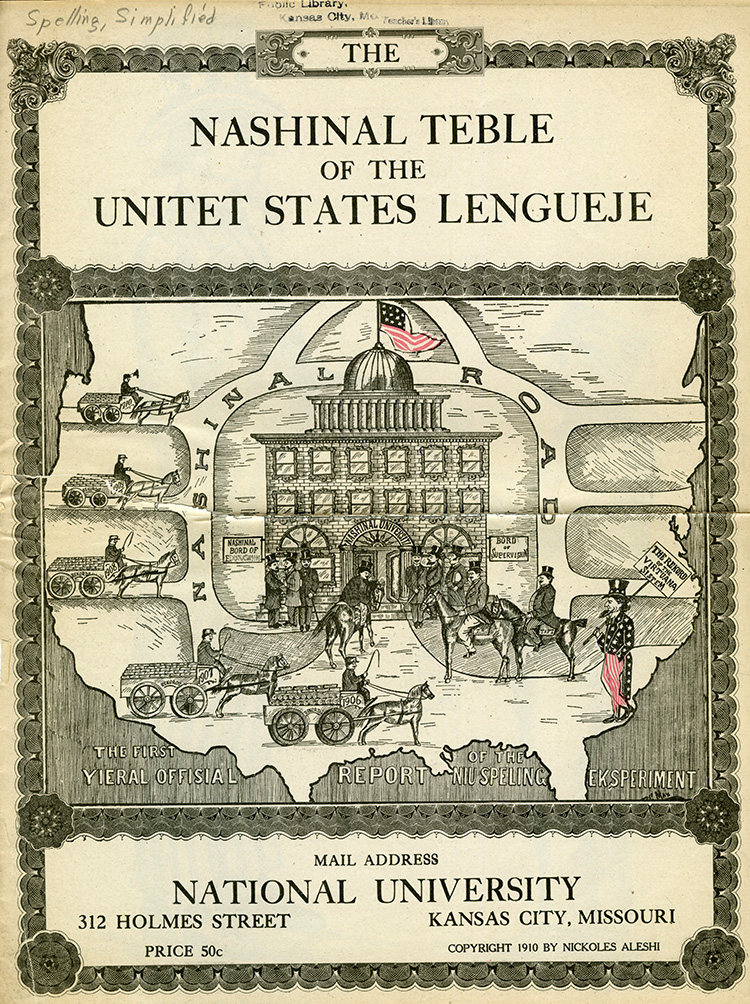

Aleshi’s first published manuscript, Eksperiment of the Virtuana Lengeuje, was copyrighted in 1909. It was one of six works related to Virtuana that he submitted to the Library of Congress for copyright.

The following year, he released the Nashinonal Tebel of the Unitet States Lengueje, a 16-page manual detailing the history, rules, and merits of Virtuana. It included a map of Missouri with names of all the “Kountis” and “Kountisiets,” as well as color map of the Unitet States, which was also sold as a souvenir in local bookstores.

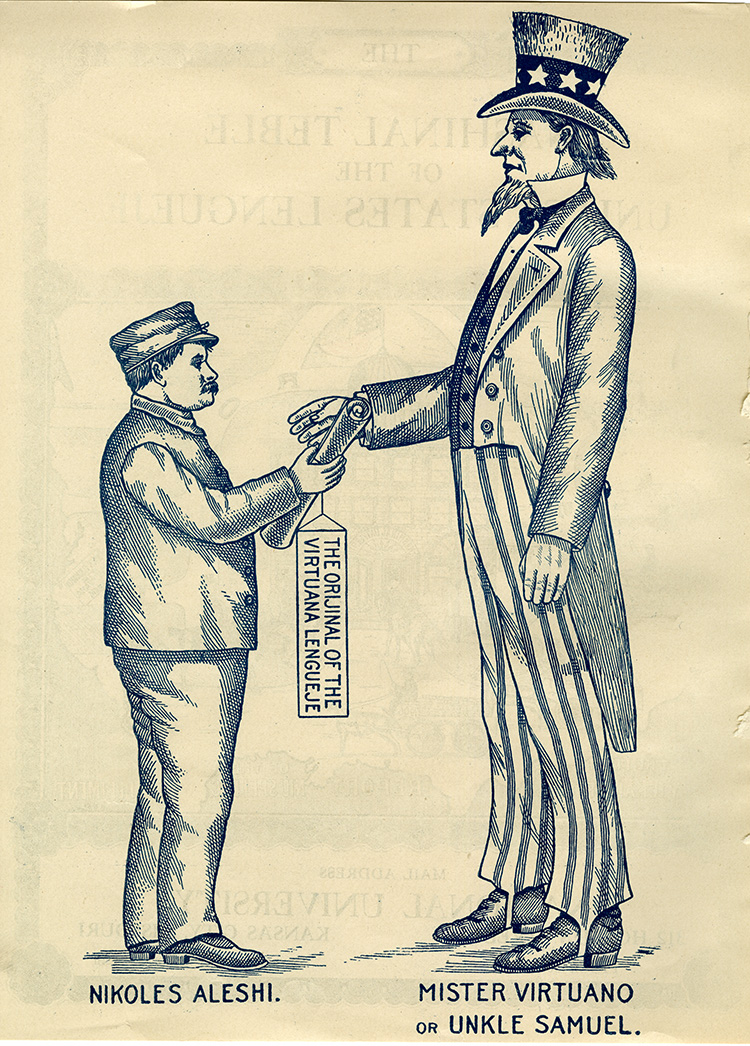

Aleshi believed his work was an act of patriotism. He felt a nation as great as the U.S. deserved a language that was uniquely American. Virtuana was his gift to his adopted country, but it came at great personal expense. From 1906 to 1910, he invested nearly $2,300 and dedicated countless hours in developing and promoting his new language. He would later claim to have invested upwards of $6,000 in total or roughly $175,000 in today’s dollars.

Aleshi printed circulars, calendars, and other publicity materials, which were mailed to newspapers and educational institutions across the country. He also wrote letters to state governors in the hope they would see the utility of Virtuana and influence state school boards and universities to adopt the new language.

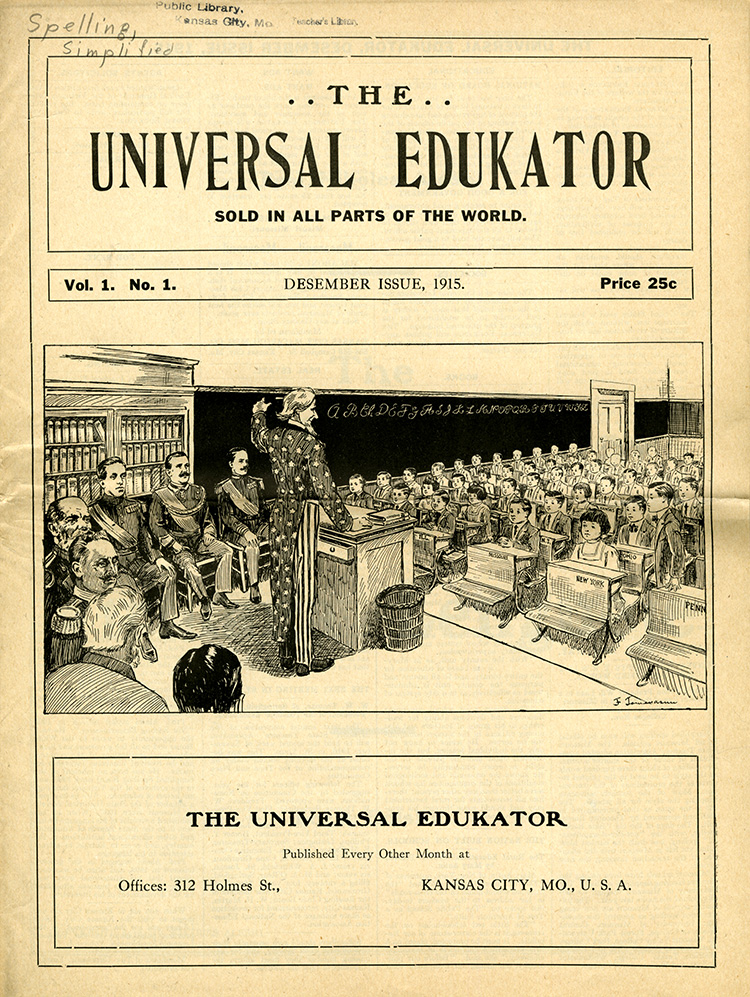

In 1915 he launched The Universal Edukator, a newspaper “published for the welfare of the Virtuana literature.” But lacking paid advertisers, only the one issue was produced.

For his efforts, Aleshi was able to garner some publicity and the support of like-minded spelling reformers. He formed a six-person “Judisari Kommittii” around 1910 to analyze and improve Virtuana.

James Greenwood, then superintendent of Kansas City, Missouri, public schools, proclaimed that Virtuana was a “system well worth investigating,” a quote that Aleshi frequently included in promotional material.

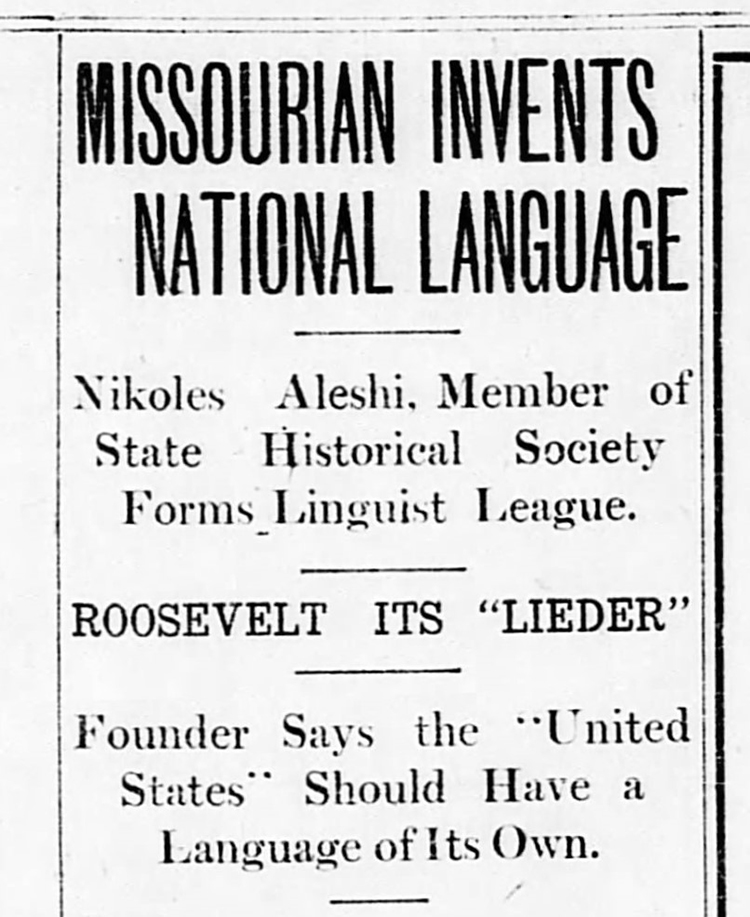

Local and national newspapers printed stories about the Kansas City grocer who had created a new language. Aleshi purported that presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Howard Taft had found merit in his spelling system.

Despite the publicity, Virtuana failed to take root. Aleshi became discouraged and attempted to sell his copyright. When no offers came, he surrendered all rights to the U.S. government, hoping that others would pick up the mantel.

But he would not completely abandon his crusade for a new national language. A Kansas City Star reporter interviewing Aleshi in 1917 noted a “gleam in his eye” when questioned about Virtuana.

Aleshi lamented that his lack of a formal schooling and broken English were obstacles in selling Virtuana’s potential as a viable language. “The educated people,” he said, “must take it up and we will have a language all our own. Someday, in three or four generations it may be.”

Nearly a decade later, in 1926, Aleshi published The Fontolina Souvenir commemorating both the U.S. sesquicentennial and the 20-year anniversary of Virtuana’s conception. The booklet was a condensed version of previously published material on the history and rules of Virtuana, and was a product of another Aleshi business venture, the “Internashional Advertising Kompani.”

That same year, Aleshi donated manuscripts and other materials to the Kansas City Public Library so future practitioners of Virtuana would have access to them. He also had records preserved at the State Historical Society of Missouri, of which he was a member.

During his final years, Aleshi suffered a series of strokes that left one side of his body paralyzed. Despite his failing condition, he continued to write letters and promote Virtuana until his death in 1931.

Although his dream of a uniquely American language went unfulfilled, Aleshi’s story embodies the American spirit of a nation founded on the ingenuity and fortitude of immigrants.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.