KCQ: How Did Kansas City Come to Be?

In hindsight, Kansas City’s development as the largest city in western Missouri seemed inevitable. Its location at the confluence of two rivers made it a likely transportation hub and a gateway for westward expansion.

But as reader Ken Truax pointed out, Independence was once the city destined to make it big in the region, and he wondered how Kansas City took over that role. While exploring KC’s origins, we also take up Michael Vuinovic’s question: How did Westport, which isn’t close to the rivers, become such a significant part of Kansas City’s development into a dominant trade community?

This week’s edition of "What’s Your KCQ?” examines how it wasn’t inevitable that Kansas City would evolve as it did. In reality, it was a combination of the natural landscape, enterprising investors, and aggressive politics that put it on the national stage.

During the 19th century’s westward expansion, the Missouri River was used by travelers to get as far west as river transportation would allow. Traveling by water was much faster than over land. But once voyagers got to the western edge of Missouri, they had to leave their boats behind.

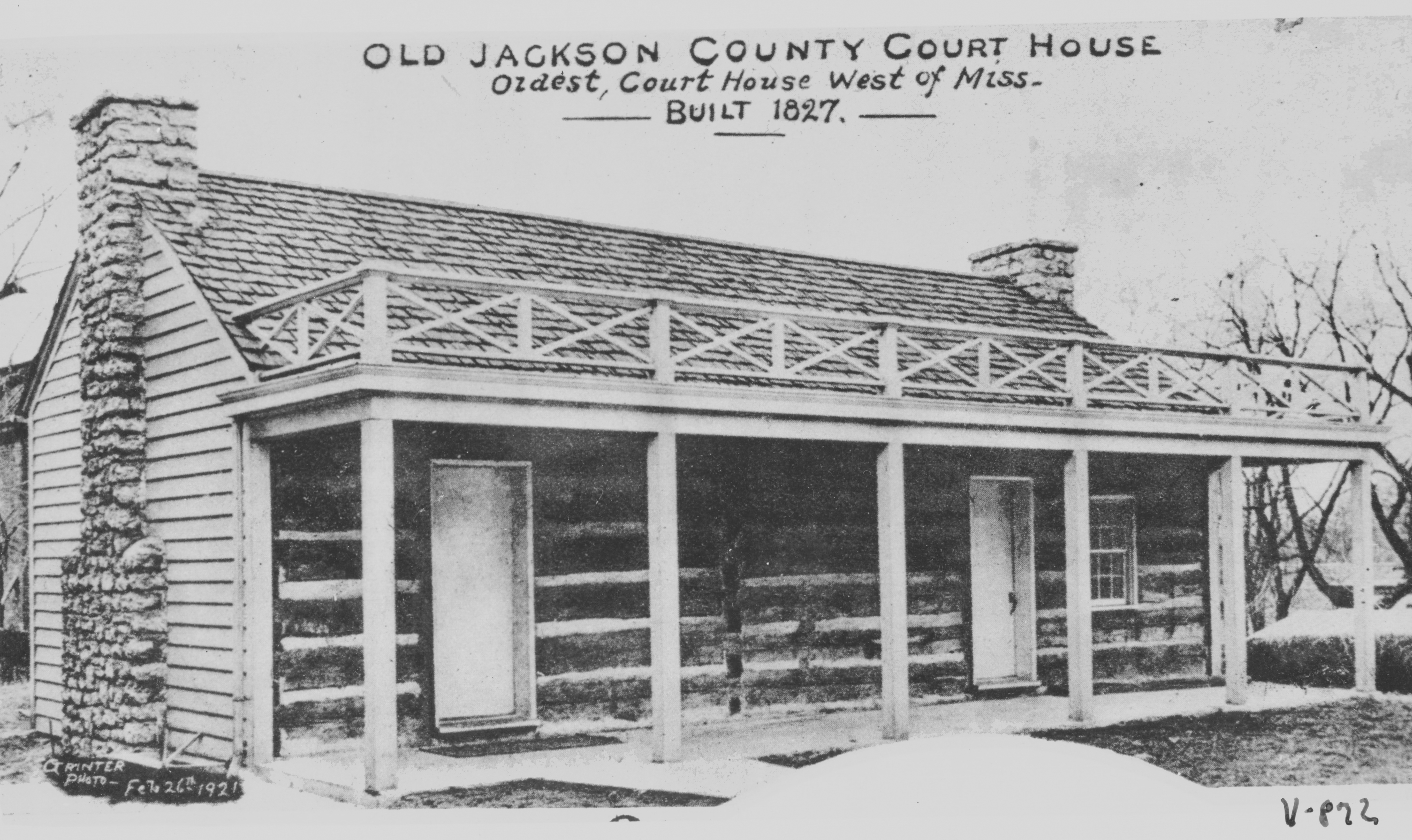

Independence, founded in 1827, was the first such “jumping off” point. The town was established about 4 miles south of the river as a courthouse location for newly formed Jackson County. By the early 1830s, it had become a major outpost for traders traveling to and from Santa Fe, New Mexico. While it was common practice at the time to situate county seats away from major waterways, the trajectory of Independence’s development could have been much different had the town been settled nearer the wide Missouri.

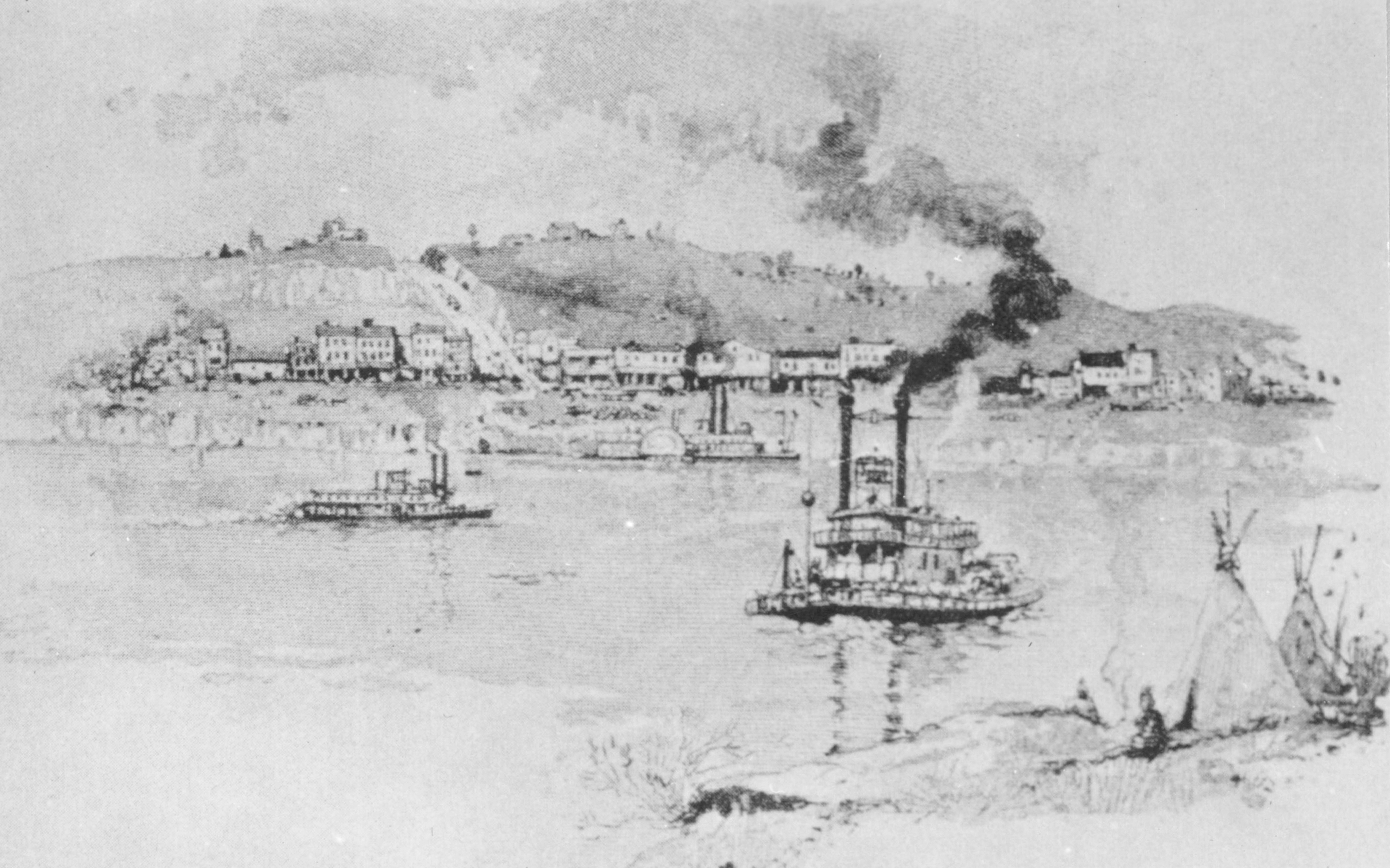

Around the same time that Independence was being settled a French fur trader named Francois Chouteau was building a community further west at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers. Chouteau’s settlement included a trading post at the bend of the Missouri, located first on its north bank near Randolph, and moved after a devastating flood to the south bank near the foot of present-day Grand Avenue. Not far away, another early developer of Kansas City would make his own mark.

In 1831, Baptist minister Isaac McCoy established a mission west of the Kansas River in what is now northern Johnson County, Kansas. Its purpose was to help serve the thousands of Delaware, Wyandot, and Shawnee Indians who had just been relocated to the area.

McCoy’s son, John Calvin McCoy, saw the potential for a nearby trading settlement. In 1833 he founded the town of Westport about four miles south of Chouteau’s old trading post. Taking inspiration from Chouteau’s river landing, he carved a path through the bluffs from Westport to a rocky outcropping next to Chouteau’s outpost. Known as Westport Landing, it connected his town of Westport to the river and provided a convenient path for goods being transported between the two. Soon, it rivaled Independence as the primary river jumping-off point for travelers and traders heading west.

Although Westport and its river landing’s initial success was due in large part to McCoy’s enterprise, the area’s long-term growth was owed to several geographic advantages. First, it was farther west along the Missouri River than Independence. For westward travelers, that meant covering more distance by riverboat, saving time and money. Westport’s prosperity can also be attributed to its proximity to Kansas Territory and lucrative trade with the Indian tribes who were forced to resettle there in the 1830s. Later, when the Santa Fe trade took off, traders coming up from the southeast preferred the closer location of Westport over Independence.

Following Westport’s success, a group of 14 investors got together in 1838 to form the Town Company with the purpose of extending the town building to land along the river. Among them was John McCoy, who folded his Westport Landing into the area that became the Town of Kansas. It was then incorporated as the City of Kansas in 1853 and later renamed Kansas City.

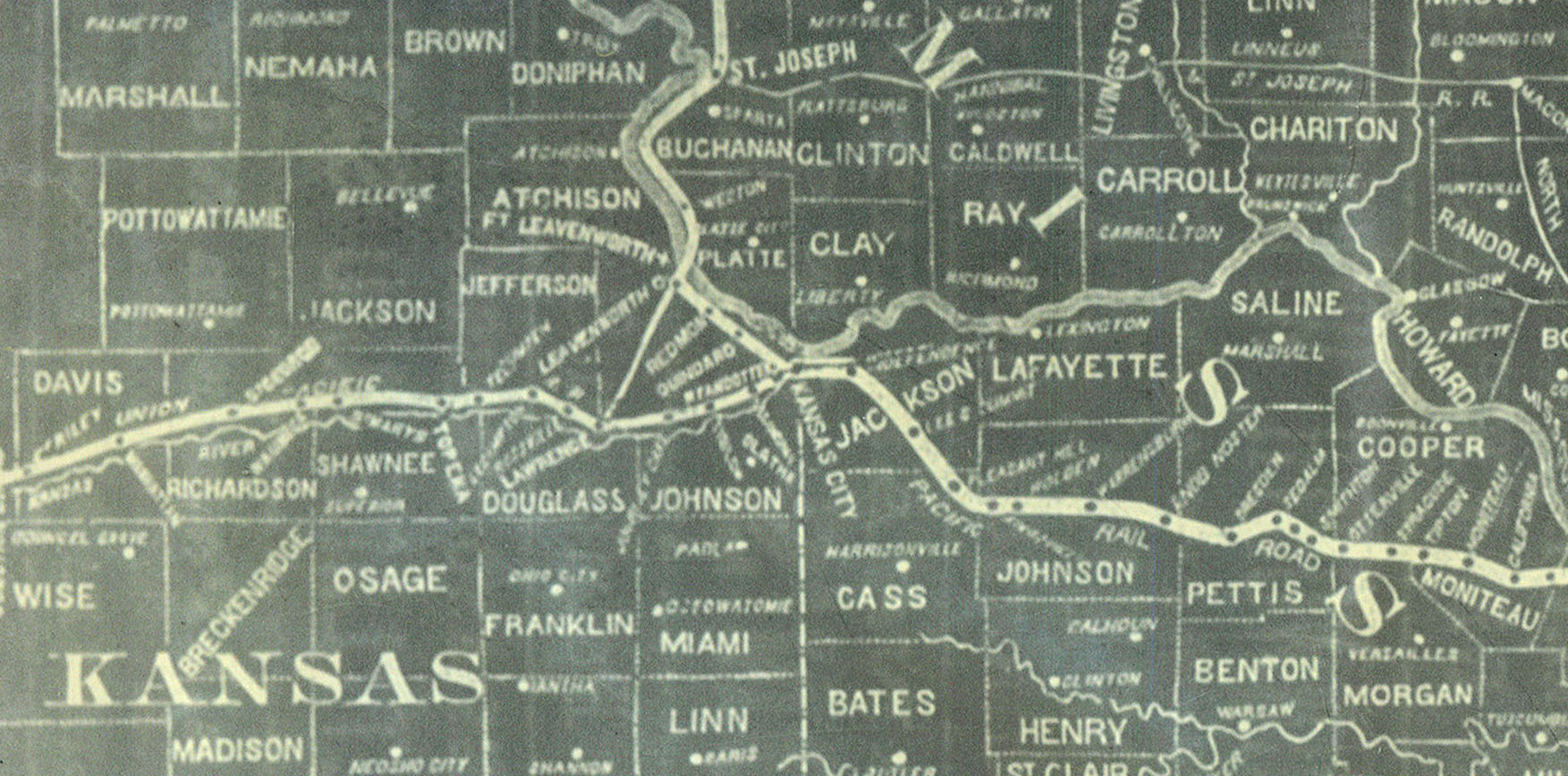

Although the advantages of river travel and overland trade are what initially attracted attention and investors to the new city, it was railroads and cattle business that eventually established the Kansas City area as the major metropolis in the western half of Missouri.

In 1862, the Pacific Railroad Acts were approved by the federal government to promote construction of a transcontinental railroad. This was followed by a flurry of new railroad lines. Kansas City boosters realized that the development of rail infrastructure and terminals in the city would be a catalyst to its growth. In his book Kansas City Railroads, Charles Glaab said “it was the pattern of railroad connections that was ultimately responsible for the fact that Kansas City, a candidate favored by few observers, ultimately became the regional metropolis.”

The Pacific Railroad line was initially organized by St. Louis investors in 1849 with the promise of connecting St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean via a railroad line running through Kansas City. The Civil War delayed construction, but the line finally reached Kansas City in September 1865, completing an East-West connection that was essential to the city’s growth.

The next step in ensuring its place as a major railroad hub was developing a northeast route and connection to Chicago livestock markets. Investors planned to lure the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad to Kansas City, but traversing the Missouri River at Kansas City was still a big problem in the early 1860s. A new bridge was needed.

Kansas City wasn’t the only city in the running for this important connection to the North. Other river cities like St. Joseph, Missouri, and Leavenworth, Kansas, had investors working to attract the railroad. When Kansas City won congressional approval to build the first bridge across the Missouri, it secured the opportunity to become the region’s agricultural, manufacturing, business, and rail center.

Thanks to the engineering ingenuity of Octave Chanute, the Missouri River was spanned with the completion of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869. It proved to be the catalyst for Kansas City’s transformation from small frontier town to thriving city. Not only did the bridge drastically expand the potential for railroad connections through the region, it also led to the arrival of the cattle trade and Kansas City’s development into the second-largest livestock market in the U.S.

Accordingly, the city saw its population surge from 4,418 in 1860 to more than 160,000 by 1900.

Submit a Question

Have a Kansas City question of your own? If selected, Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.