KCQ Explores the History and Legacy of Kansas City’s Pioneer Mother

With Mother’s Day weekend approaching, it is fitting that What’s Your KCQ? respond to a query about Kansas City’s Pioneer Mother sculpture in Penn Valley Park.

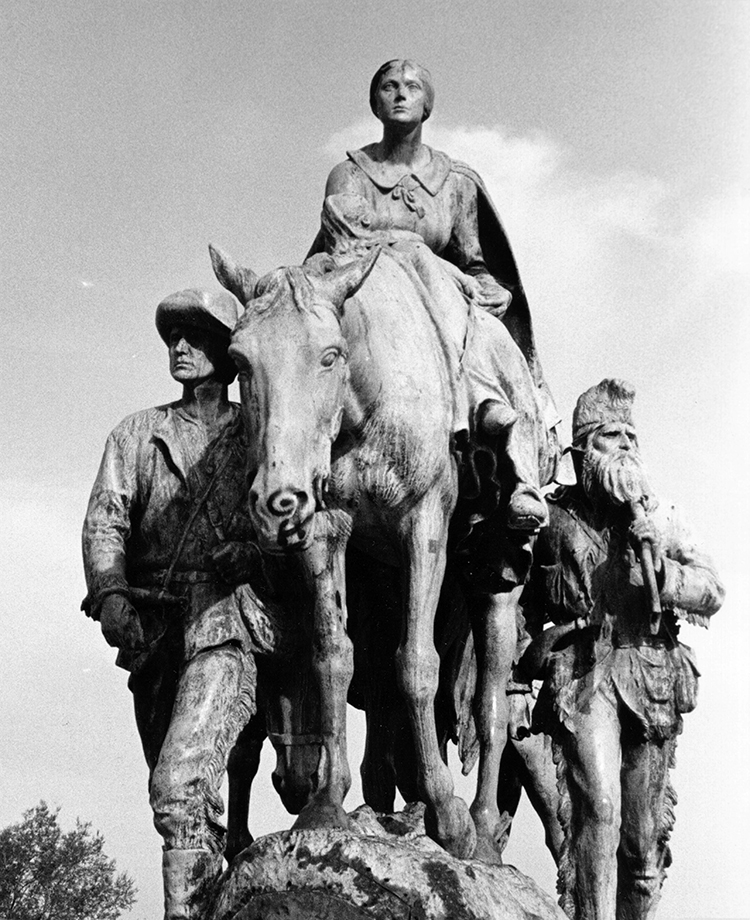

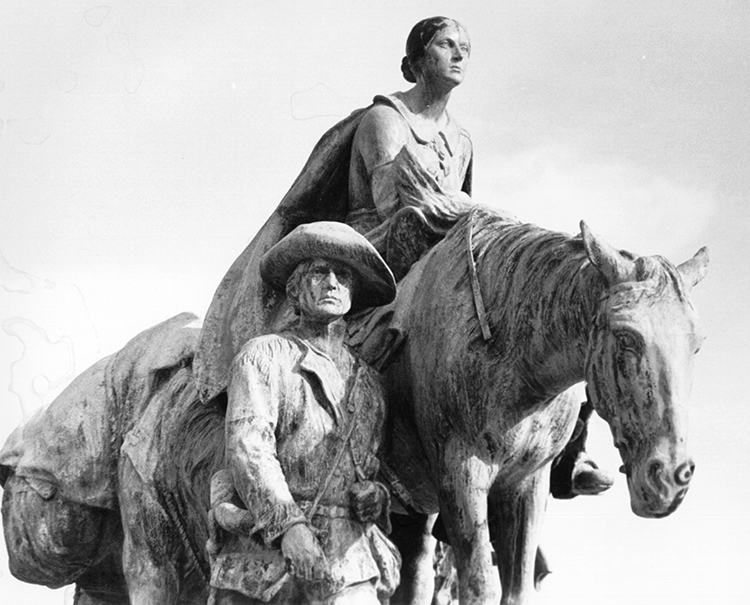

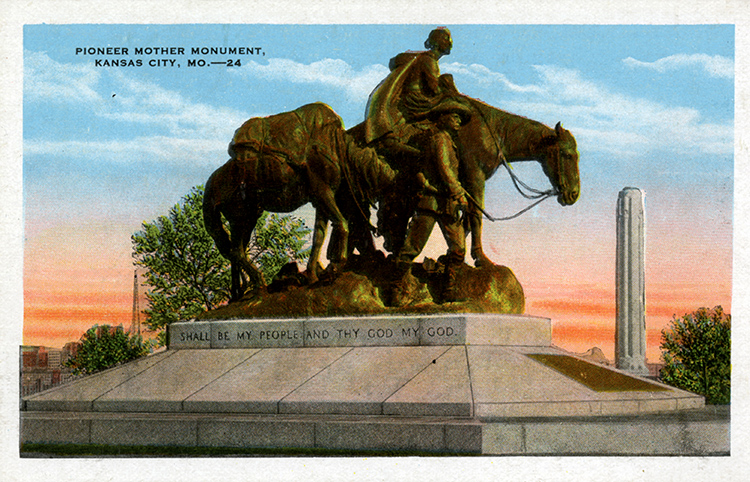

A memorial to mothers who made the arduous trip west to seek better lives for their families, the 13-foot bronze statue depicts a woman perched sidesaddle on a mount, holding an infant, her expression reflecting grim determination and exhaustion. She is flanked by two men with rifles, who serve as scouts and protectors, and a weary pack horse.

The monument, dedicated November 11, 1927, bears the inscription: “Presented to the people of Kansas City by Mr. Howard Vanderslice to commemorate the Pioneer Mother who with unfaltering trust in God, suffered the hardships of the unknown West to prepare us a homeland of peace and plenty.”

What’s Your KCQ? reader Jesse Barker was curious about the history of the sculpture and the Kansas Citian who commissioned it, Howard Vanderslice. Furthermore, if the statue depicts a pioneer family traveling westward, Barker asked, “why are they heading southeast?”

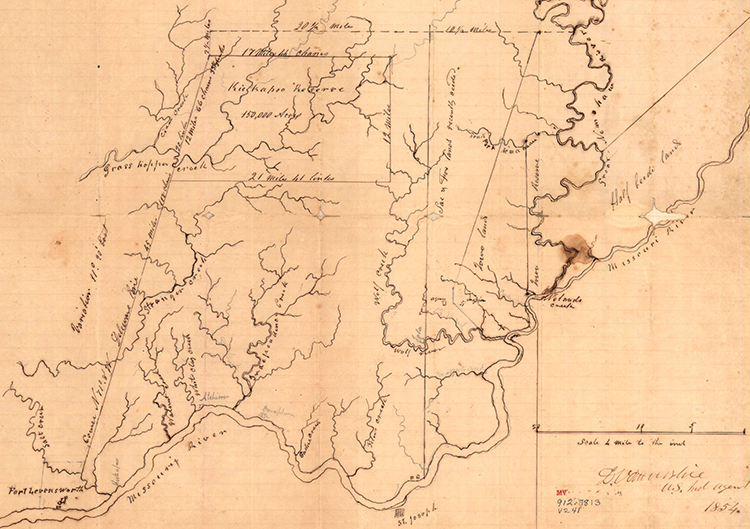

The story of the Pioneer Mother begins with the Vanderslice family’s emigration from Kentucky to Kansas Territory in 1853. The same year, Congress passed an Indian appropriations bill that cleared a path for white encroachment on Indian lands in Kansas Territory.

Howard’s grandfather, Maj. Daniel Vanderslice, was appointed by President Franklin Pierce to serve as U.S. Indian agent to the Iowa, Kickapoo, and Sac and Fox tribes in northeast Kansas Territory. His father, Thomas Jefferson Vanderslice, was assigned to give instruction in cultivating crops on the reservation.

Howard was about 4 months old when his mother Sarah Jane, father Thomas, and paternal grandparents began the journey west on foot and horseback to what is now Doniphan County in northeast Kansas.

The party crossed the Missouri River at Westport Landing in August 1853 and headed northwest, settling in present-day Highland, Kansas. The men assumed their duties in Indian affairs, while Sarah and her mother-in-law Nancy built a home life on the western frontier.

Reflecting on his early childhood on the plains, Howard Vanderslice said, “The women did so much yet so little was heard of them.”

They were Kansas pioneers. Howard Vanderslice’s father was elected to the territorial legislature in 1860, the state legislature in 1868, and served two terms as Doniphan County sheriff.

Howard worked as a youth on the family farm and later attended Highland University in his hometown. He relocated in 1873 to Iowa Point, Kansas, took a job as a station agent for the Atchison and Nebraska Railroad, and married Minnie Elizabeth Flinn. The couple then settled in nearby White Cloud, Kansas, where Howard established a grain business.

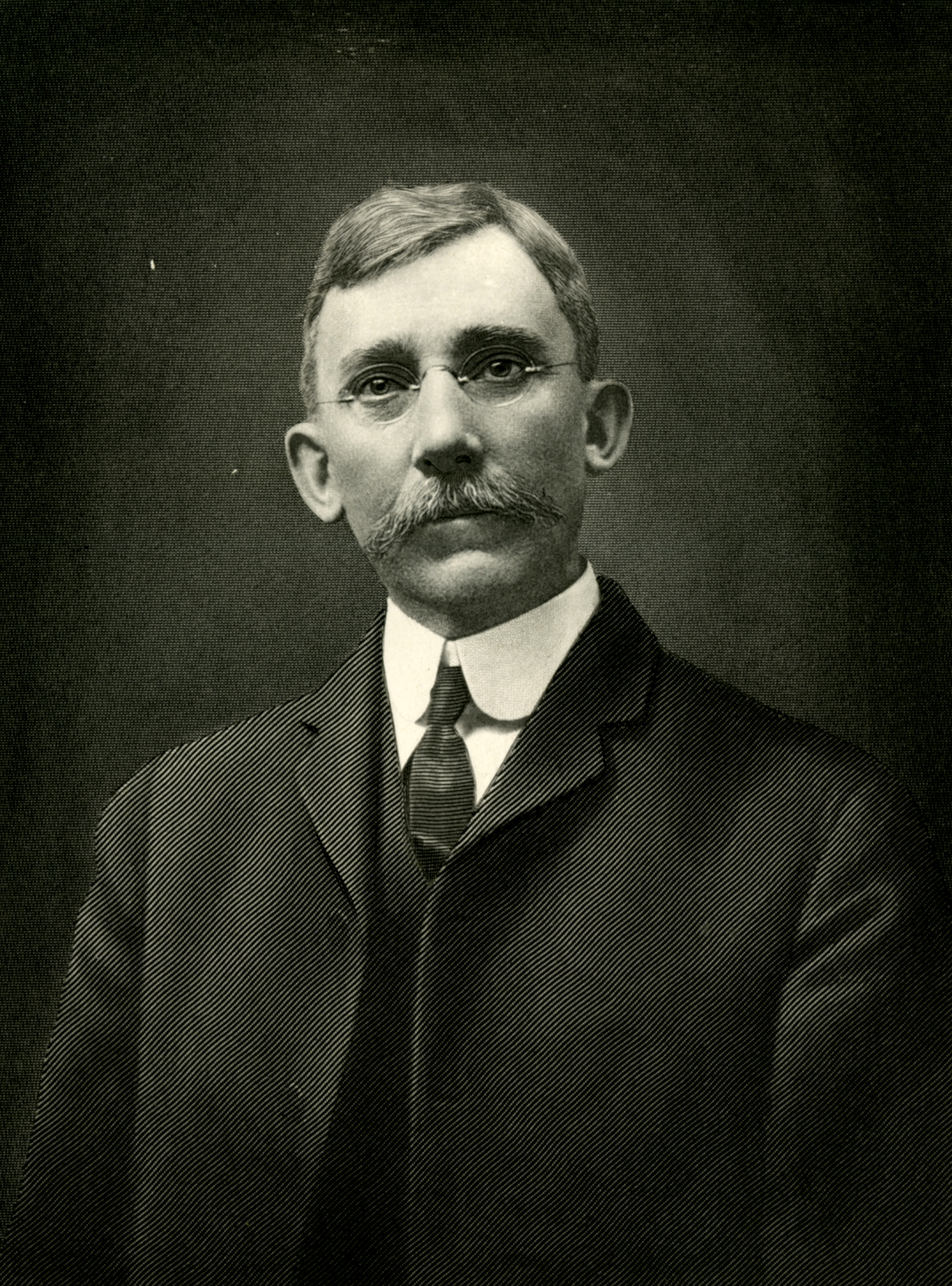

Wishing to expand into a larger market, he opened a grain commission house in Kansas City in 1890 and put down roots there. He later invested in another lucrative commodity, purchasing the Central Ice Company in 1907.

By the 1920s, Vanderslice had earned considerable wealth through his various business enterprises.

Wanting to honor the sacrifices of his mother and other pioneer women, as well as the city he now called home, he commissioned celebrated western artist Alexander Phimister Proctor to immortalize his family’s journey in sculpture. In Proctor, Vanderslice saw a fellow man of the West who was also the son of a pioneer family.

THE ARTIST

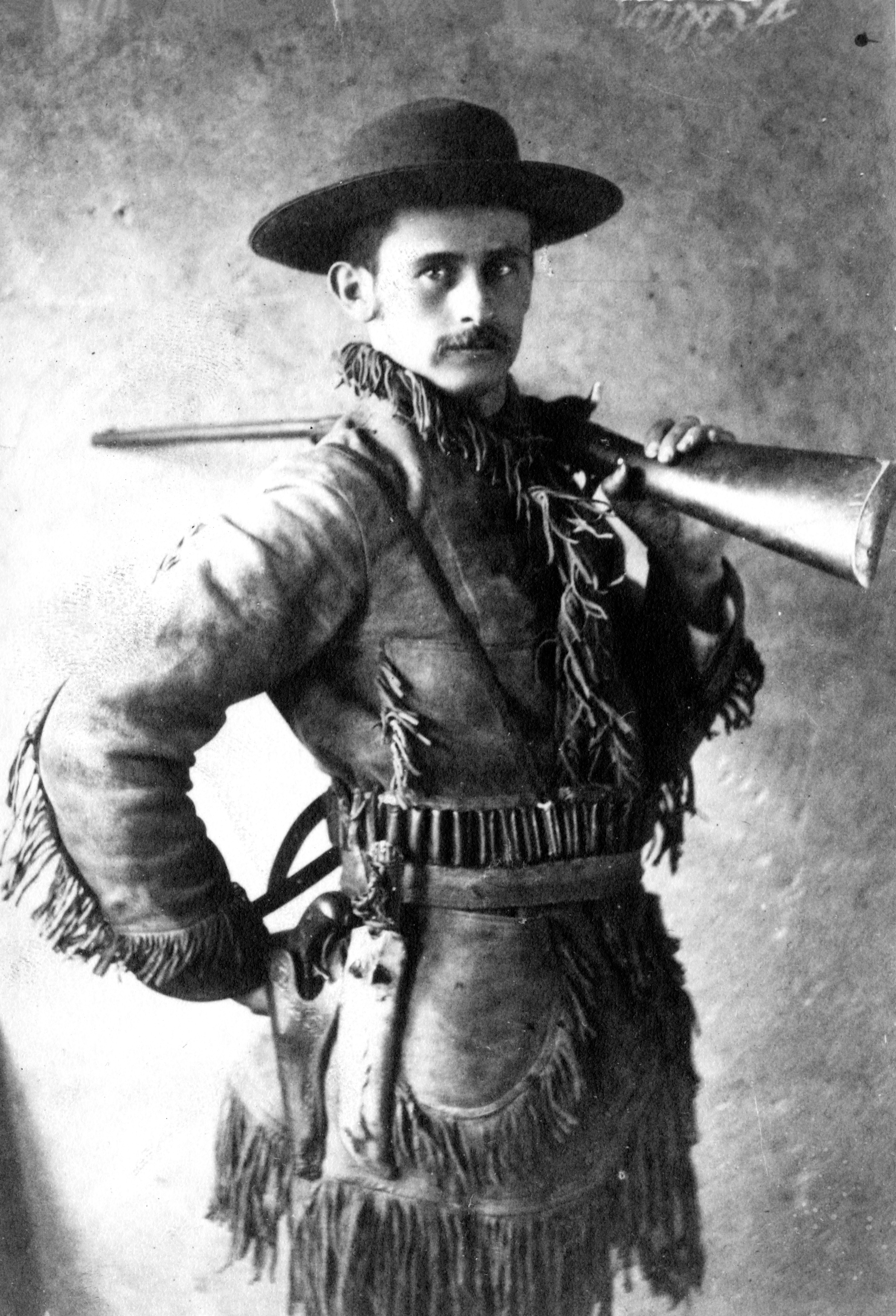

Raised in Colorado after his family emigrated by wagon from Iowa in 1871, Proctor became infatuated with hunting and sketching Rocky Mountain wildlife. While his initial art training took place in Denver, he also studied in New York and Paris.

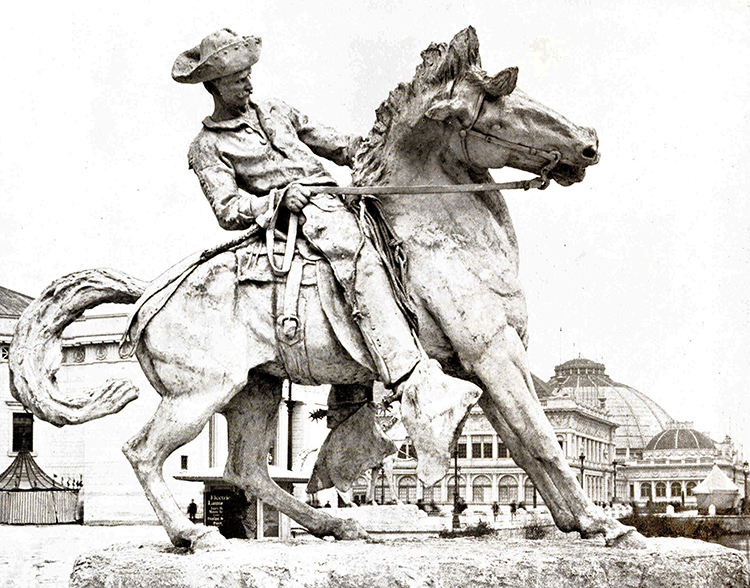

His first major commission came in 1891 when he collaborated with a team of esteemed artists to create sculptures for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

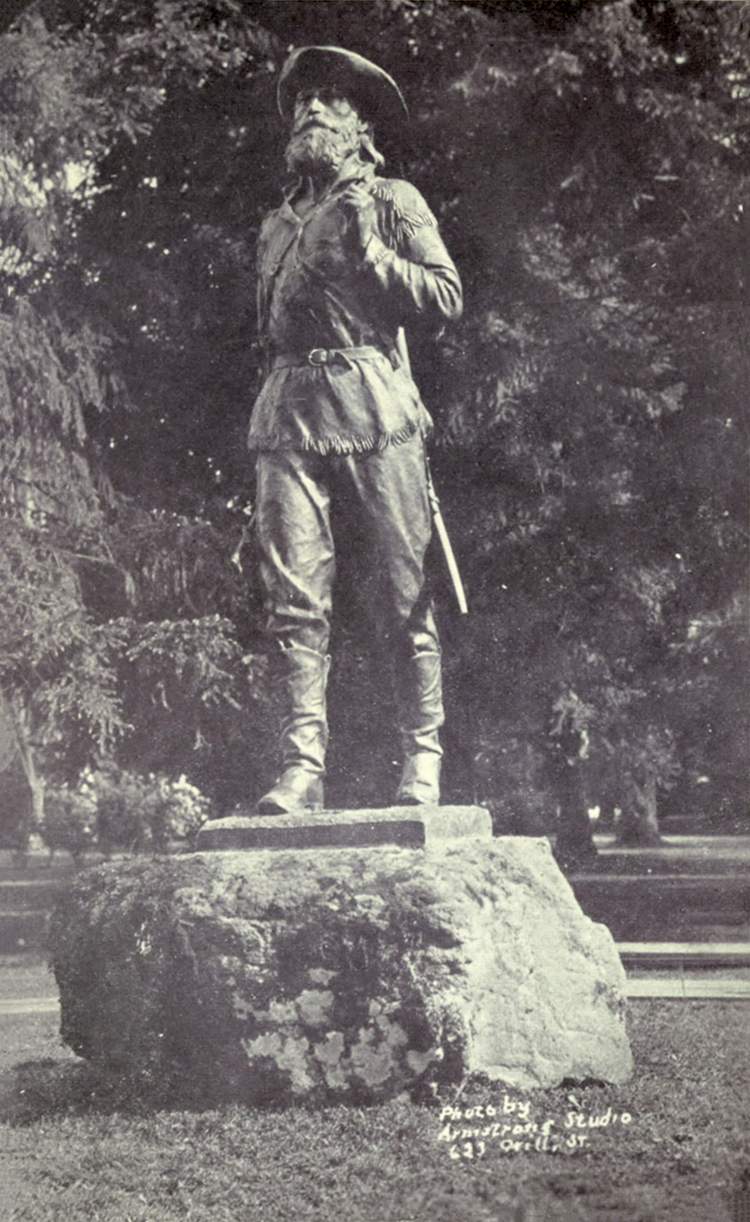

In the years to follow, Proctor, the self-proclaimed Sculptor in Buckskin, made a name for himself creating monumental bronze sculptures of American Indians, cowboys, buffalo, and other iconic imagery of the American West.

In 1923, Vanderslice approached Proctor at an art show in Los Angeles about crafting a monument to heroic pioneer mothers. The artist was interested in the subject matter, having already created a pioneer monument in 1919 for the University of Oregon campus.

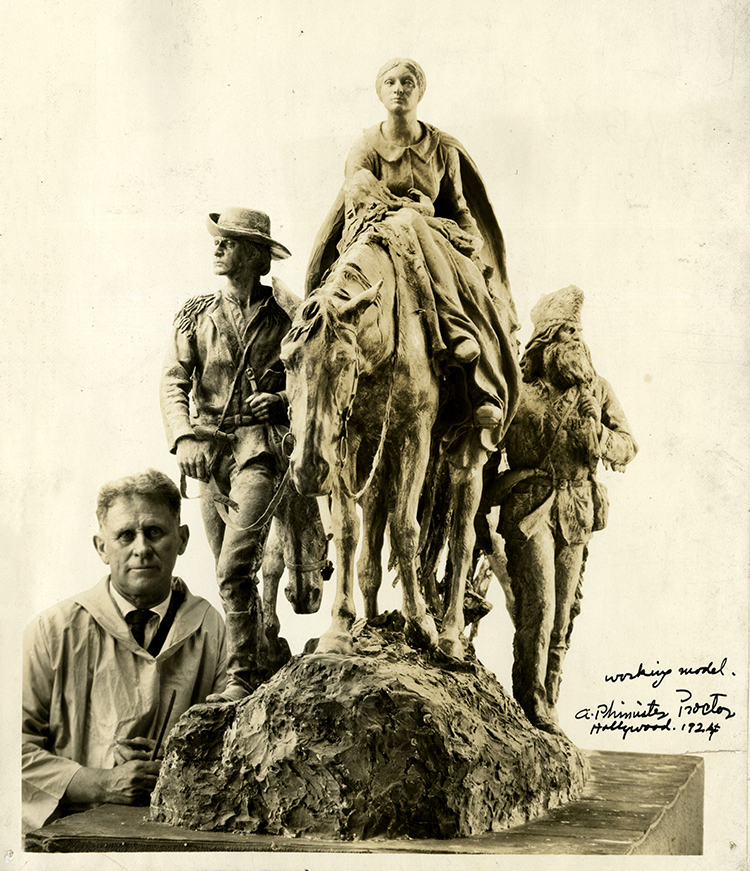

Proctor began work on a 4-foot-tall, 6-foot-long model based on details provided by Vanderslice about his family’s 1853 migration. He worked out of a studio in Hollywood, California, where human models and props were easier to procure. The completed model was then shipped to Proctor’s New York studio.

The casting was completed in Rome, Italy, where according to Proctor, he could find more skilled artisans for that type of work. When the 16,000-pound bronze statue was completed in 1927, it was transported by ship and rail to Kansas City.

THE UNVEILING

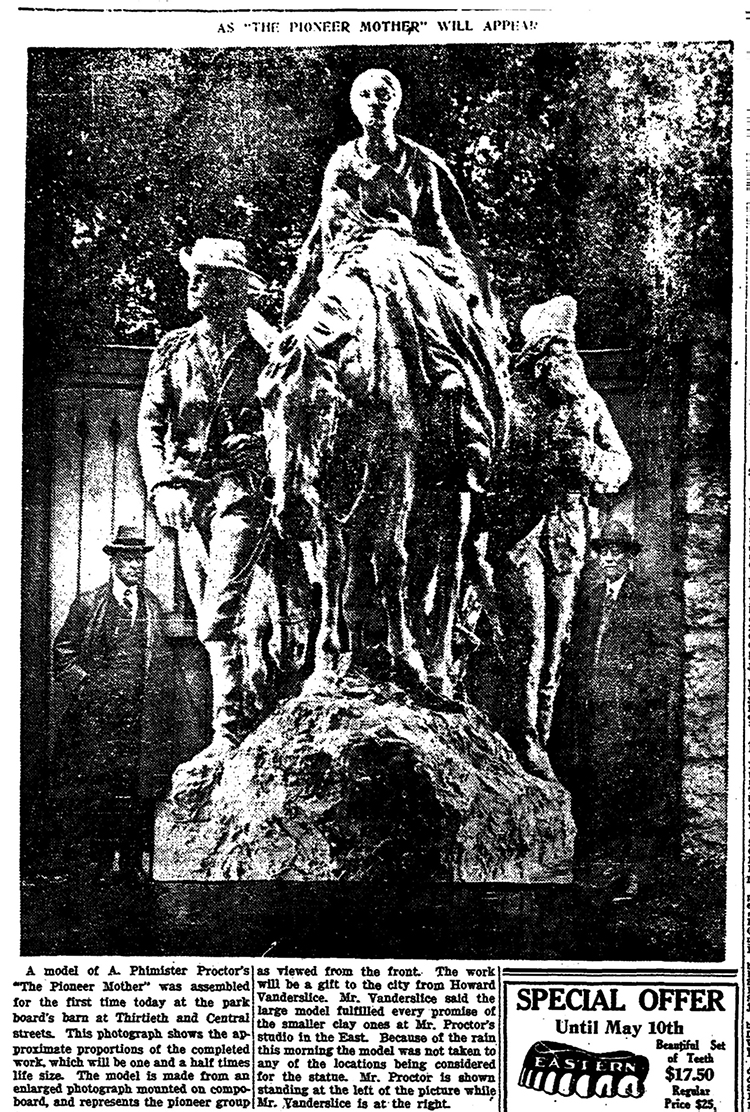

Potential sites for the statue had previously been studied using an enlarged, 14-foot-tall by 8-foot-wide mounted photograph as a model. The Kansas City Arts Commission recommended Meyer Boulevard near the entrance to Swope Park. Westport was also suggested, considering its early history as a trails outpost.

A knoll in central Penn Valley Park, a few hundred feet from the old Santa Fe Trail, was preferred by Proctor and Vanderslice. The park provided ample room to view the statue at multiple angles and was the site of two other iconic monuments, the Liberty Memorial and The Scout.

Large slings were employed to lift the 6-ton statue onto a pink granite pedestal designed by the prominent Wight & Wight architectural firm. It was installed facing southward.

When questioned why it did not look west, in the direction the pioneer group was traveling, Proctor’s pragmatic response was, “A statue shows to the best advantage when facing south and should never face any other way unless it is impossible to have it in that position.” By being oriented southward, the face of the statute received optimal lighting.

An estimated 5,000 people, including Proctor, attended the unveiling on November 11, 1927. The modest Vanderslice refused to take part in the ceremony or have his name on the program.

Despite his absence, the dedication was very personal for Vanderslice, memorializing his family’s migration west to the prairies of Kansas and his own mother carrying him on horseback during the wearisome journey.

He viewed the Pioneer Mother as a uniquely American artistic form and subject, a departure from the classical works of Europe. “It is time for an American expression in the arts,” he told The Kansas City Star, “and that expression will have to be on native topics, since those are the ones we know best.”

Vanderslice died from a stroke in 1929. He is best remembered for his work in promoting the arts and purchasing the estate of industrialist August Meyer at 44th Street and Warwick Boulevard to donate to the Kansas City Art Institute for its campus. The institute’s Vanderslice Hall, formerly the Meyer residence, was named in his honor.

THE RESTORATION

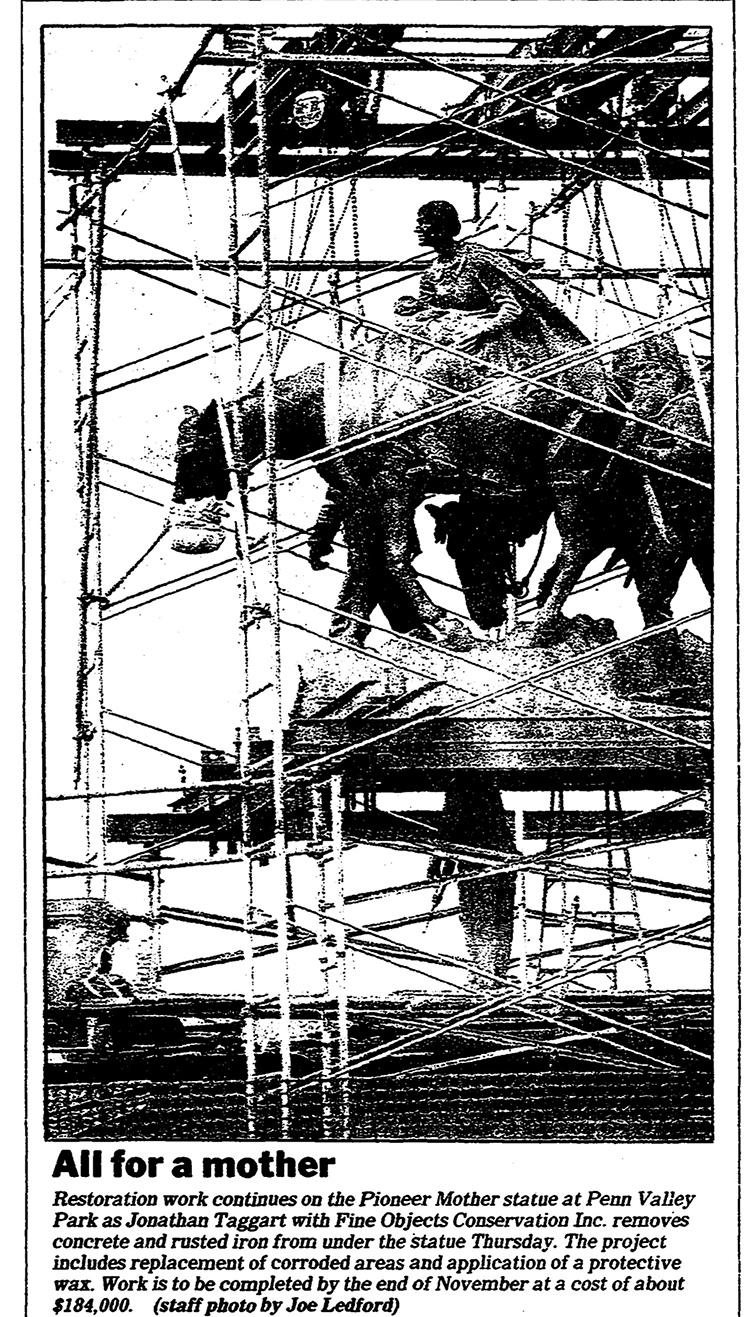

Some 50 years later, the Pioneer Mother was showing its age. Decades of exposure to the elements and vandals left the statue in decay. It was rusting from the inside, creating cavities, and had become structurally weak.

In 1988, a team of conservationists worked onsite for months to clean and repair the statue. They removed dirt and graffiti from the surface, replaced corroded iron rods used to reinforce the horses’ legs, and referred to historical photographs to recreate missing parts.

The refurbished sculpture was rededicated in a modest ceremony on May 14, 1989. It remains in Penn Valley Park as a tribute to pioneer mothers and Kansas City’s frontier heritage.

THE LEGACY OF PIONEER MEMORIALS

Honoring pioneers through public art wasn’t unique to Kansas City. Dozens of pioneer memorials were erected throughout the western U.S. in the early 1900s.

After the close of the American frontier in 1890 (when the U.S. census that year showed no territory remaining without pockets of settlements), many municipalities and heritage organizations began memorializing their pioneer forefathers and mothers by erecting monuments. It was not only a way to acknowledge the fortitude of their forbears but also celebrate frontier history and nostalgia, and promote heritage tourism.

Historian Cynthia Culver Prescott, in her book Pioneer Mother Monuments: Constructing Cultural Memory, contends that pioneer memorials reflected the prevailing cultural superiority of early 20th century Anglo-Americans. They “celebrated the arrival of white civilization (in the form of manly pioneers and saintly Pioneer Mothers),” Prescott wrote, “to the allegedly untouched western wilderness and supposedly savage (uncivilized) indigenous peoples.”

As there has been recent public debate among communities about the merit of Confederate monuments, pioneer memorials and similar monuments to westward expansion have also been scrutinized.

For some, these monuments celebrate the American pioneering spirit and western heritage. Others view them as markers of displacement, poverty, and cultural assimilation suffered by Indigenous peoples whose ancestors were forced to cede lands and relocate.

In May 2019, on the 100-year anniversary of the unveiling of Proctor’s statue The Pioneer at the University of Oregon, students from the school’s Native American Student Union protested the bronze figure of a frontiersman, armed with a whip and rifle, as a symbol of white supremacy. Demonstrators later toppled the statue, and it was removed to storage.

Locally, statues of Jackson County namesake Andrew Jackson outside the county courthouses in Independence and Kansas City have been debated.

Critics questioned the veneration of the country’s seventh president through public art considering he was a slave owner and authorized the forced removal of thousands of Indians from their native lands. Jackson Countians ultimately voted to leave the statues in place in 2020. Plaques were added that gave a more nuanced picture of Jackson’s legacy.

What’s Your KCQ? wants to hear from the Kansas City community. Does the Pioneer Mother still hold significance as a memorial to the city’s pioneering past? Or is it a vestige of a period that largely ignored the devastation wrought on Native Americans by white settlement of western lands?

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.