Kansas City’s post-WWI Black social club. What’s Your KCQ? investigates the Beau Brummel Club

In 1920s Kansas City, hotel ballrooms, restaurants, and nightclubs teemed with crowds excited to hear the region’s signature jazz sound and eager to take advantage of the city’s lax alcohol prohibition enforcement. By visiting “Paris of the Plains,” as the city was nicknamed, one could enjoy performances of everything from vaudeville to Shakespeare, or even one of the newly invented motion pictures.

For Black Kansas Citians, however, some of whom had served their country in WWI and visited the real Paris in France, much of their hometown was closed off to them.

The Beau Brummel Club stepped in to help improve the social and civic lives of Black veterans and civilians. A reader asked What’s Your KCQ? to investigate the club’s history.

By 1920, Kansas City’s Black population of nearly 30,000 had middle-class aspirations and the purchasing power to back them up. Despite this, they could not try on clothes in downtown department stores or use the front entrances of downtown movie theatres. Their children could not receive an education alongside white students, and Black educators could not teach white children.

Forming social clubs was a way for Black citizens to sidestep the racism they experienced daily. These clubs fostered a sense of community and promoted Black-owned businesses as a welcoming alternative to segregated establishments.

The Beau Brummel Club was founded in 1918 by Roy Dorsey, a tailor who also pitched a couple of games for the Negro Leagues’ Kansas City (Kansas) Giants; Percy Lee, a teacher at the Attucks School; and Felix Payne, a club owner and politician with ties to Tom Pendergast. Dorsey conceived of the club as a way of entertaining Black soldiers visiting on leave from nearby military bases and Black soldiers returning from the war.

Originally called the “Bon Vivants,” they later renamed the club after Beau Brummell, the famed British fashion influencer of the early 1800s. Like the Brummel Club in Tucson, Arizona, which also catered to African Americans, it dropped the second “l” in Brummell.

The new Beau Brummel Club took its place among other Kansas City area Black social clubs like the Cheerio Boys, the Kewpie Klub, the Harmony Art and Literary Club, the Sans Souci Club, and “Les Cinq Cents Miraculeux,” or The Miraculous Five Hundred.

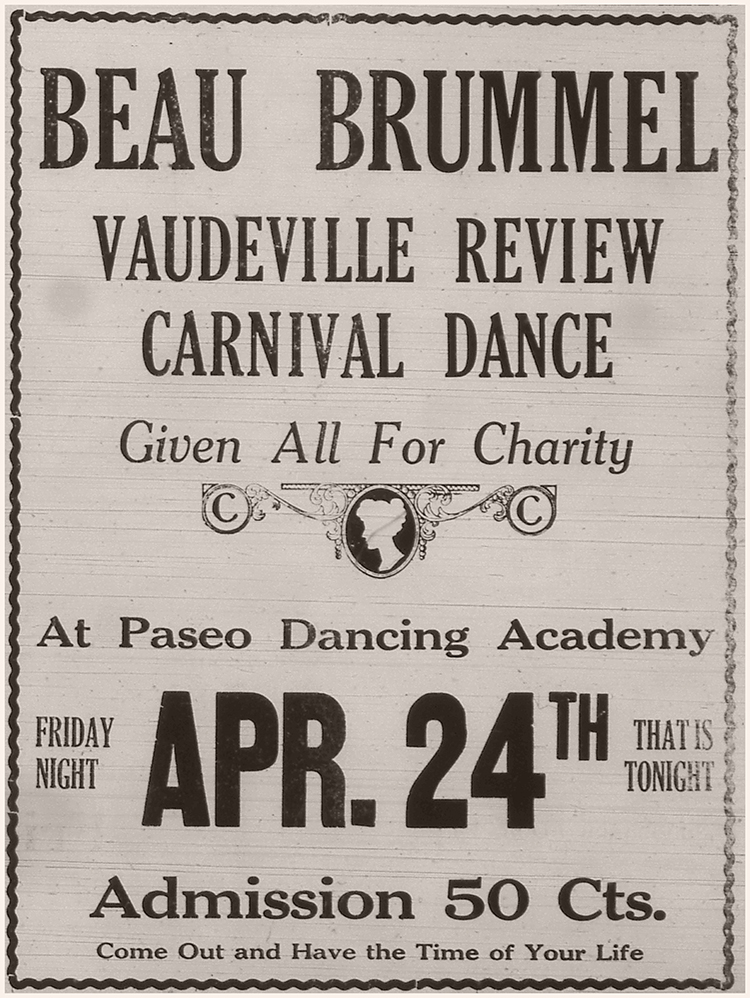

The Brummels sponsored evening entertainment to benefit Black-owned businesses. One popular outing took members to dinner at the De Luxe Café, followed by a movie at Love’s Theatre at 24th and Vine streets.

In the Labor Temple at 14th Street and Woodland Avenue, where Bennie Moten’s orchestra played three nights a week, a Brummel benefit dance raised over $300 for the struggling Paseo YWCA.

The club also raised funds for the T.B. Watkins Baseball League; Wheatley-Provident Hospital; and annual scholarships for Lincoln and Sumner high school students; as well as assisting in the defense fund for Leroy Bundy, who was accused and ultimately convicted of helping to instigate the East St. Louis, Illinois, riots of 1917. With help from the NAACP and money raised by clubs all over the country, Bundy appealed his conviction and was released after serving one year of a life sentence.

Aside from its popular philanthropic events, the annual Beau Brummel anniversary and Christmas parties were also eagerly anticipated by the Black community and always well attended.

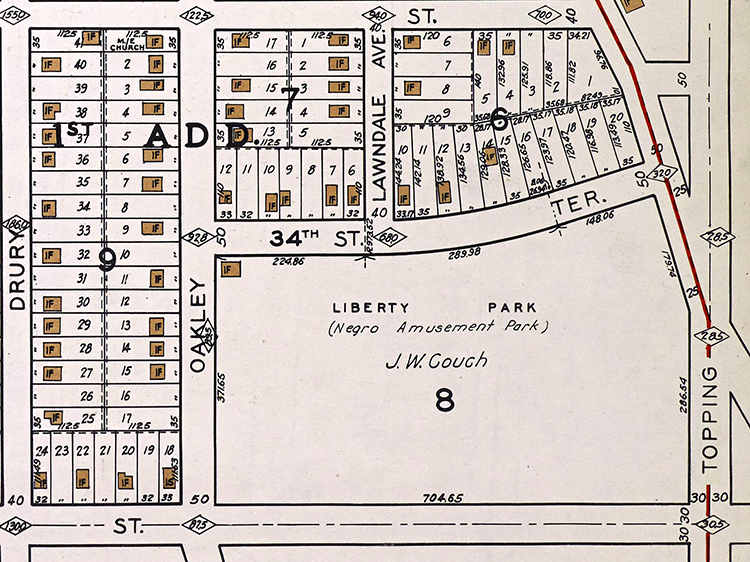

Later, Dorsey and Lee became managers of Liberty Park founded in 1922 as an alternative to the segregated Fairmount Park and Electric Park. Today, Yvonne Starks Wilson Park at Stadium Drive and East 34th Terrace occupies the Liberty Park site.

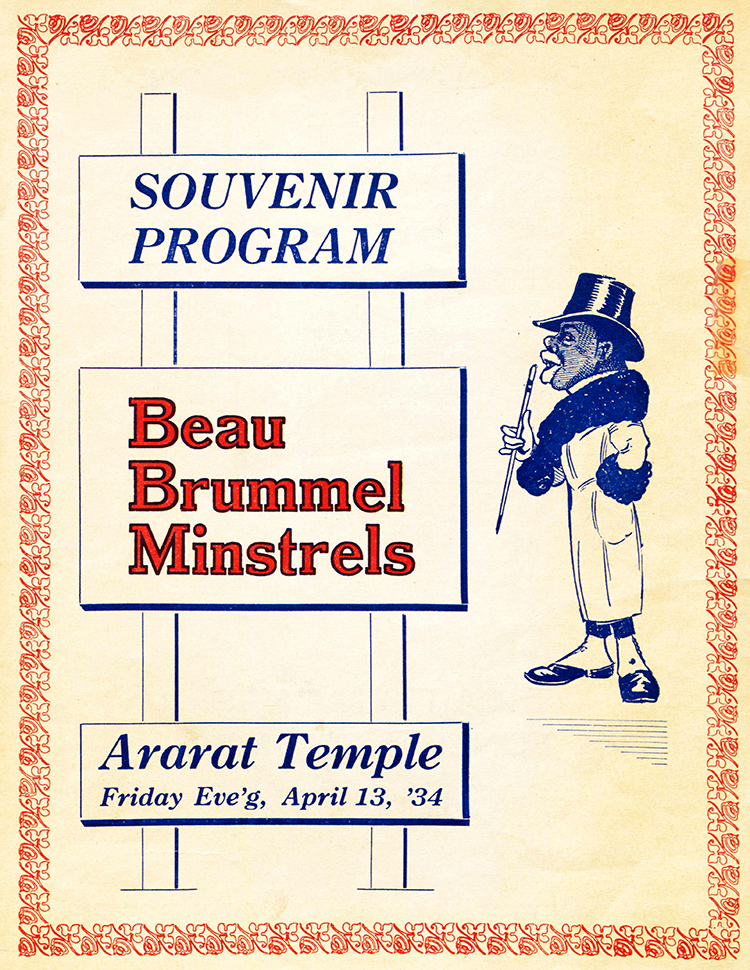

On April 13, audiences gathered at the Ararat Temple to witness a grand revue with a cast of some 200 performers. This was not the debut of the Beau Brummel Minstrels, as the troupe was known, but it was their first widely advertised performance and was a hit among Kansas Citians, Black and white. The group became a reliable source of revenue for the club.

While it may seem strange that a Black social club would put on minstrel shows, a musical theater style defined by white performers in blackface performing racially stereotyped and mocking shows for white audiences, some Black audiences were fans of the form.

Black performers began participating in minstrel shows as early as the 1840s. Among the first Black performers was William Henry Lane, known to the public by his stage name, Master Juba. Lane’s promoter at the time, P.T. Barnum, later of circus fame, encouraged Lane to darken his face with burnt cork to trick audiences into believing they were paying to see a white performer in blackface makeup.

All-Black troupes grew in popularity. White audiences likely viewed them as a novelty and may have been drawn to what they believed to be a more authentic representation of antebellum plantation life. Black audiences, on the other hand, may have felt comforted that musical and theatrical representations of their lives were being performed by Black performers.

Whatever the explanation for the popularity of minstrelsy with Black audiences, the Black community did not agree on the issue. Many simply could not overlook the racism inherent to the form — even if some Black audiences and performers may have felt empowered through their enjoyment and participation.

Despite their divisive nature, the popularity of Black minstrel shows continued into the 20th century. Over time, many troupes, including the Brummels, incorporated elements of vaudeville, burlesque, and circus sideshows, and became more akin to variety shows than traditional minstrel performances.

For the 1950 Kansas City Centennial celebration, the Brummels put on a two-night musical “supershow” revue featuring nationally recognized acts. Sellout crowds packed the Municipal Auditorium’s Music Hall to see Clayton “Peg Leg” Bates, a South Carolina-born dancer who had lost his leg in a childhood cotton gin accident, and 10-year-old Herman Lee Hanson, who in the words of one enraptured reporter “performed like the backlash of a bazooka.” Another rising star, Hortense Allen, was introduced as “Miss Body” and performed her rendition of the “jungle dance.”

The centennial performance marked a high point for the Brummels. The culmination of the club’s fundraising came in January 1953, when it dedicated a new headquarters at 1729 Lydia Avenue in the old Watkins Brothers Funeral Home. Local dignitaries, including City Manager L.P. Cookingham, Police Chief Bernard C. Brannon, and WDAF-TV news anchor Randall Jessee attended the dedication.

Over the next 10 years, the Brummels hosted events for mayoral candidate H. Roe Bartle, the Jack and Jill Club, the NAACP, and the United Negro College Fund.

Despite its success, the club experienced a decline in the 1960s. Legal segregation waned and finally collapsed. Like many of Kansas City’s East Side institutions and businesses once supported by the Black community when it had no other options, it struggled to stay afloat. By the 1970s, the Beau Brummel Club was defunct and faded into the city’s memory.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.