Kansas City vs. North Kansas City: 1940s political tussle for (more) space on the map

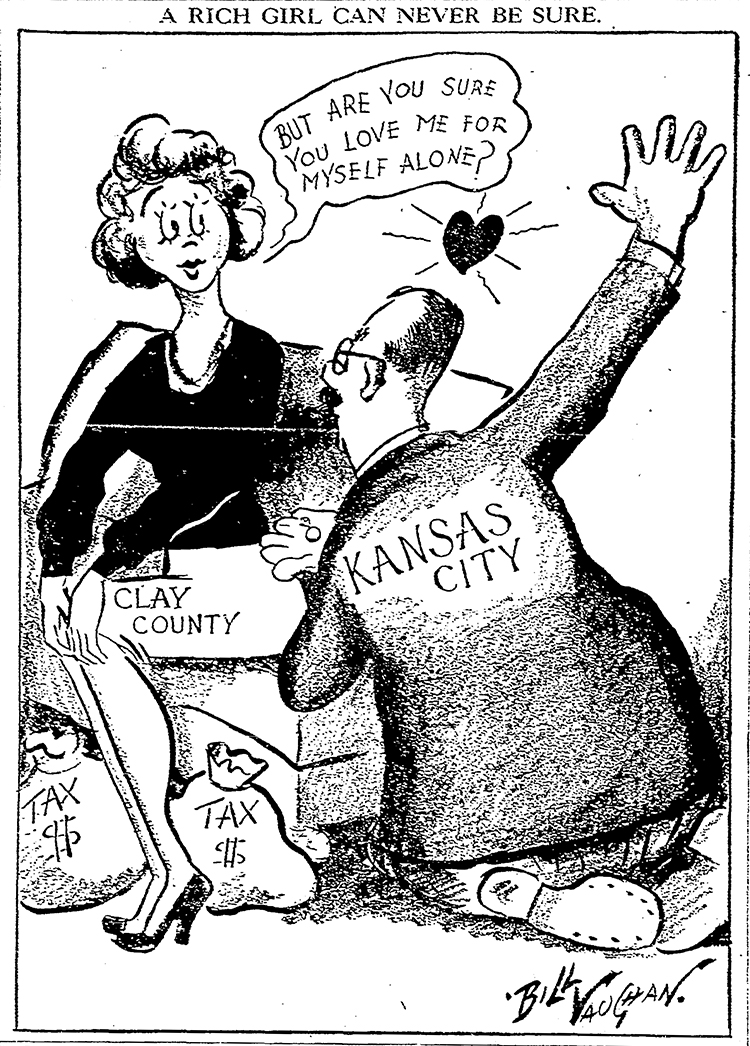

In 1946, Kansas City found itself at a crossroads. The rise of the suburbs and decentralization posed a threat to downtown, creating a postwar existential crisis for the city. Swift action was needed to halt urban decay and ensure future growth. With a tax base on the decline, expanding into unincorporated land was a logical solution.

What emerged was a tussle over an area north of the Missouri River with the city of North Kansas City, which had similar concerns and designs. The episode nearly 75 years ago was the subject of a recent inquiry to What’s Your KCQ, the community reference partnership between the Library and The Kansas City Star, from reader Nelson Nissley.

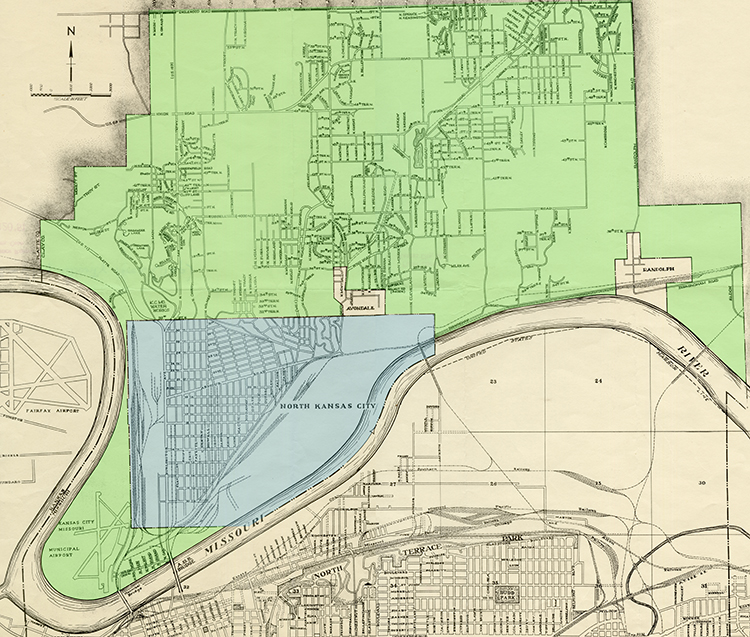

It was the citizens of North Kansas City who moved first, voting September 10, 1946, to annex an area to their north from East 32nd Avenue (near today’s Waggin’ Trail Dog Park) to Englewood Road and east just past the city of Randolph. With a final count of 801-33, the election was a landslide victory for the smaller city.

Not to be outdone, Kansas City held its own election to annex the same territory in Clay County two months later. The measure narrowly passed, but state law held that annexation approval required a three-fifths majority. Well short of that, Kansas City’s bid was declared dead on arrival.

How, then, did it ultimately get what it wanted, and then some?

The move north traced back to a luncheon meeting earlier in 1946 between mayors William E. Kemp of Kansas City and North Kansas City’s Lee Roberts. Kemp learned of North Kansas City’s intent to annex about 19 square miles of unincorporated Clay County. Upon returning to City Hall, he shared the tidbit with City Manager L.P. Cookingham.

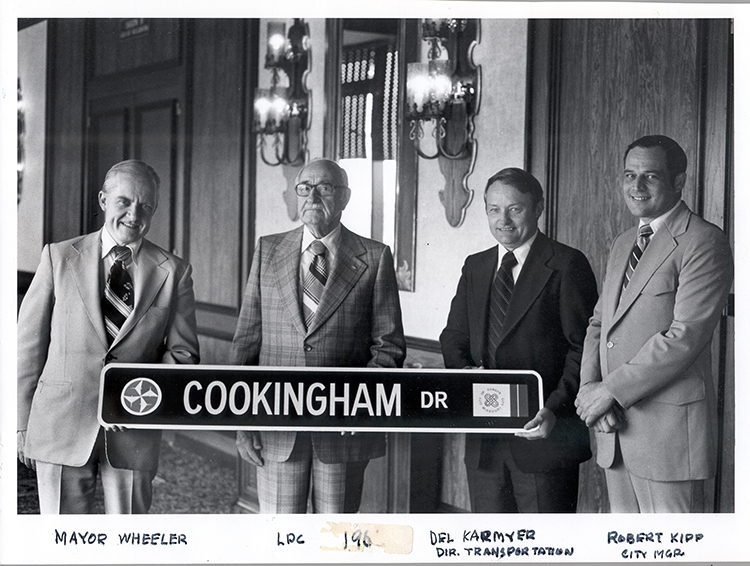

Cookingham had been hired in 1940 to replace the corruption of the Pendergast years with honest and efficient government. He was also tasked with ushering the city into the modern world. Cookingham recognized that suburban development threatened Kansas City’s economic future and could erode downtown’s importance as a center of business and industry. Annexation was the perfect way to fight decentralization – if not halting suburban development, seeing that it happened within Kansas City limits and was subject to Kansas City taxes.

The city could have pushed farther south into unincorporated Jackson County, but Cookingham felt it only would add to decentralization, permanently relegating downtown to the city’s northernmost region. With the Missouri-Kansas state line to the west and Independence to the east, moving north made more sense. If successful, downtown’s status as a central hub could be preserved.

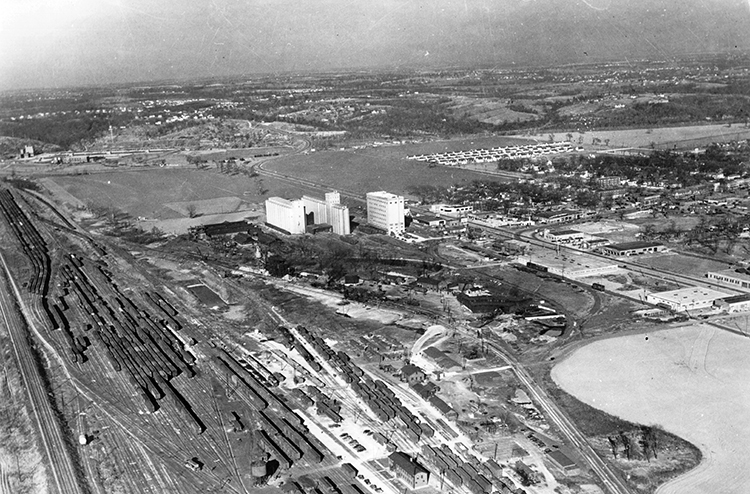

In addition, Cookingham wanted to redevelop the East Bottoms and rebrand it as the Northeast Industrial District. With a projection of up to 50,000 new jobs, new housing in the vicinity would be needed. Clay County was a perfect fit. And like most Americans in the 1940s, Cookingham had automobiles on the brain. Anticipating federal assistance for a national network of highways, he realized that annexations would give the city greater control over future regional highway and bridge planning.

Time was of the essence since North Kansas City’s plans were already in motion. Cookingham quickly and quietly had a proposal drawn up, making sure to keep his plan secret from likely opponents on the city council – two Pendergast Machine holdovers representing the city’s 1st and 3rd wards. Together, they represented Kansas Citians from the state line east to city limit, and from 31st Street north to the river, an area encompassing the city’s Hispanic community in the west, Italian enclave in the north, and Black neighborhoods in the east. This constituency had helped keep the wheels of the machine running smoothly for decades until Boss Tom’s fall (Tom Pendergast served time in prison for tax evasion. He was indicted in 1939).

In the 1940s, most Clay Countians did identify as Democrats, but they emphatically did not identify as Pendergast Democrats. If Cookingham’s plan was successful, their districts would naturally be extended north into Clay County, a move that would dilute the old Pendergast voting blocs and threaten their positions on the council.

In addition to keeping certain city council members in the dark, Cookingham reached out to Kansas City Star editor Roy A. Roberts and asked for the newspaper’s discretion and support. Roberts, who liked the plan, agreed to keep quiet until the move was made public and promised the newspaper’s backing.

Finally, at 4 pm, just before the council was scheduled to meet on August 19, all members were called to a meeting in Mayor Kemp’s office and the plan was revealed. As Cookingham expected, the proposal passed with only two dissenting votes from the Pendergast holdovers. Kansas Citians would vote on the annexation ordinance that November.

With the news out, matters in North Kansas City kicked into high gear. Its annexation proposal was introduced a few days later and an election was scheduled for September ahead of Kansas City’s. Mayor Roberts hinted at his city’s willingness to fight out the matter in court if the Kansas City ordinance passed.

Battle lines were drawn, but a very important constituency was omitted from the discourse – namely, Clay County residents living in the annexation zone. As a matter of law, the two cities understood that only their respective citizens could vote on the ordinances.

Existing cities in Clay County didn’t have to worry about annexation. Avondale, just east of North Kansas City, had been around since 1916, Randolph since 1920. Claycomo had incorporated earlier in 1946. In the annexation zone, however, more than 7,000 people would have no voice in the September and November elections. It did not sit well with them at all.

What did they stand to gain if annexed?

Cookingham promised infrastructure, new housing, land development, lower water rates, and such city services as fire and police protection. Moreover, he insisted that all of this could be provided with no tax increase – to existing Kansas Citians, of course.

Many living in the annexation zone weren’t impressed.

Vocal opponents insisted they had settled in rural Clay County specifically to avoid the troubles associated with city living. They wanted to raise livestock, grow their own food, and generally didn’t see the need for a city hall to tell them what they could and couldn’t do on their land. Also, living outside of city limits kept them free of city taxation. While city dwellers might avoid a tax hike, they most assuredly would not.

The covert manner in which Kansas City had crafted its proposal added to their resentment. This, combined with anger over being excluded from the vote, led to public statements framed in the language of the American Revolution – “No taxation without representation!” And if their land had to be gobbled up in what was viewed as a shady, backroom deal, they would much rather North Kansas City do the gobbling.

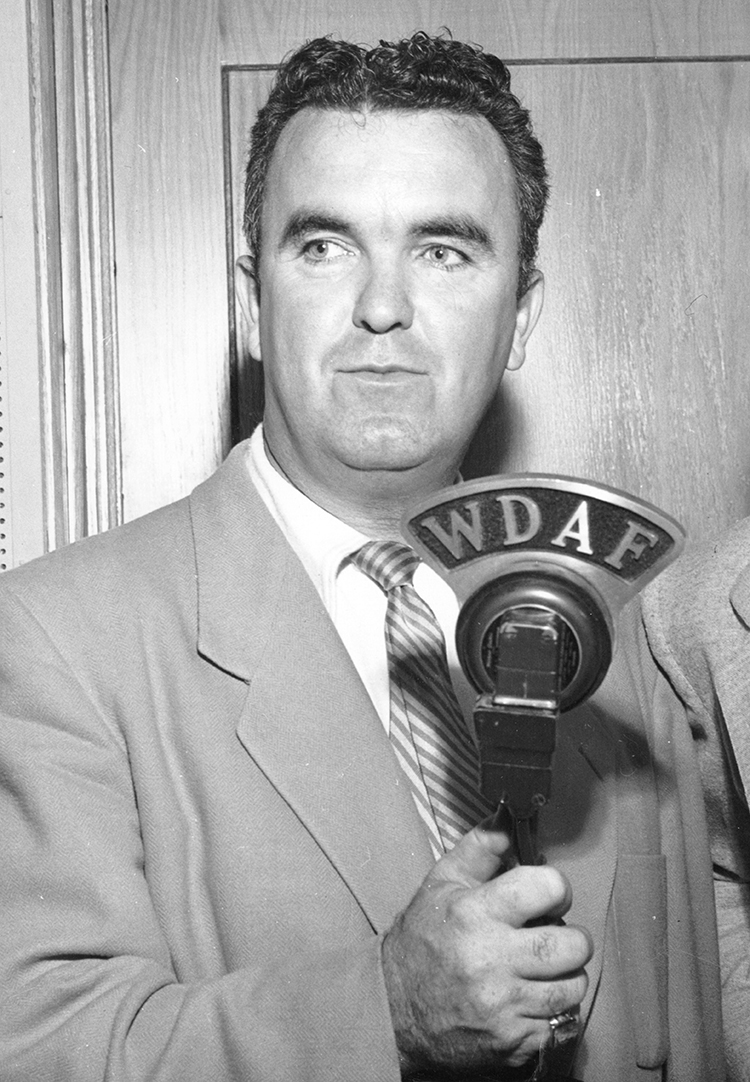

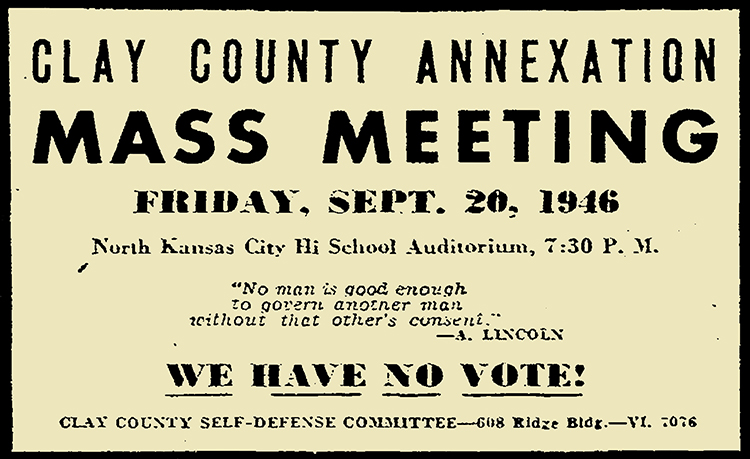

The hostile feelings kindled grassroots organization. Taking the lead against Kansas City’s annexation move was the Clay County Self-Defense Committee. Randall Jessee, a Clay County resident who was news director for television station WDAF, was appointed chairman. With his broadcasting background, Jessee naturally served as the voice of the disenfranchised group.

At a meeting at North Kansas City High School on August 27, a resentful crowd of more than 1,000 heard Cookingham’s arguments in favor of annexation before having its spirits lifted by Jessee. He reminded the assembled mass that their struggle was shared by the likes of Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and Patrick Henry.

Cookingham and his supporters came back, maintaining that Clay County residents stood to benefit from Kansas City’s future development and should therefore pay their fair share. The crowd appeared unconvinced.

As the debate progressed into fall, the rhetoric grew more charged. Signs on cars read “Remember the Sudetenland – Remember Hitler,” comparing Cookingham’s annexation plans to Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938.

The Clay County Self-Defense Committee and other groups continued their fight, holding meetings, and – if allegations by annexation supporters are believed – conspiring with Pendergast Democrats in Kansas City to sway voters. In late-September the Self-Defense Committee vowed to cover all of Kansas City’s election expenses if annexation zone residents were allowed to vote. Kansas City politely declined the offer.

Some fought by other means. A group of Platte County residents seeing no reason why Kansas City would limit its ambitions to Clay, filed for incorporation as Platte Woods before either annexation vote was held.

Shortly thereafter, North Kansas City declared victory with its successful election on September 10.

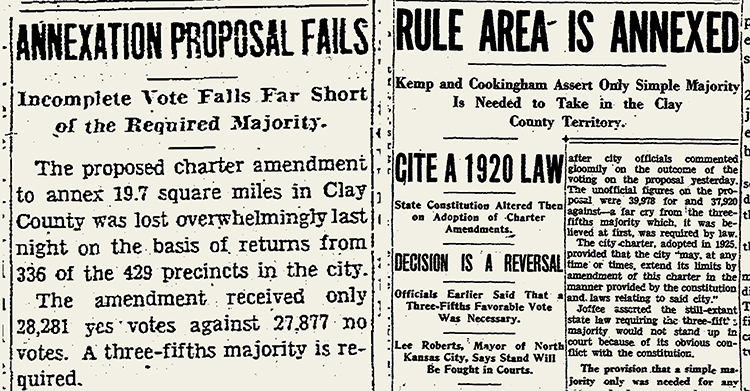

Kansas Citians headed to the polls on November 5. In a last-ditch effort, the Clay County Self-Defense Committee arranged for about 100 North Kansas City High School students to be excused from classes so they could hand out sample no-vote ballots at polling locations south of the river. By the next morning, the votes were counted – 39,978 for annexation to 37,920 against, falling more than 6,700 yes votes short of the three-fifths majority needed for passage. North Kansas City, with its 96% mandate, celebrated and vowed to extend city services to the annexation zone by January 1.

Cookingham was not pleased. Years later, he would recall ruminating on the election results the following morning, saying to Mayor Kemp, “I’m not satisfied with this. Let’s go down to the law books and take another look.” The desperate city manager pored over legal texts all morning, searching in vain for the source of the three-fifths provision, eventually declaring that it must not exist. Therefore, Cookingham believed, Kansas City’s ordinance had actually passed.

A city attorney was initially dismissive of the claim. “Show it to me,” Cookingham challenged. Upon deeper examination, it was learned that the three-fifths rule for annexation had been changed to a simple majority requirement in 1920 and not reenacted when the state constitution was amended in 1945.

Cookingham was right. The ordinance had passed.

The Kansas City Times had already run a story headlined “Annexation Proposal Fails” that morning. Cookingham quickly notified the media of his discovery, and the evening Kansas City Star carried the news of the city’s victory. The Clay County Self-Defense Committee called the action a “moral injustice.”

There was one hurdle left to clear – the fact that North Kansas City had held a successful annexation election two months earlier. Mayor Roberts believed the election date preempted Kansas City’s claim and vowed to fight. Cookingham countered that whichever city’s annexation proposal was introduced first, and not which one was voted on first, would carry the weight of law. The lawyers went to work.

Following three years of litigation, the Missouri Supreme Court sided with Cookingham. Kansas City had officially moved into Clay County.

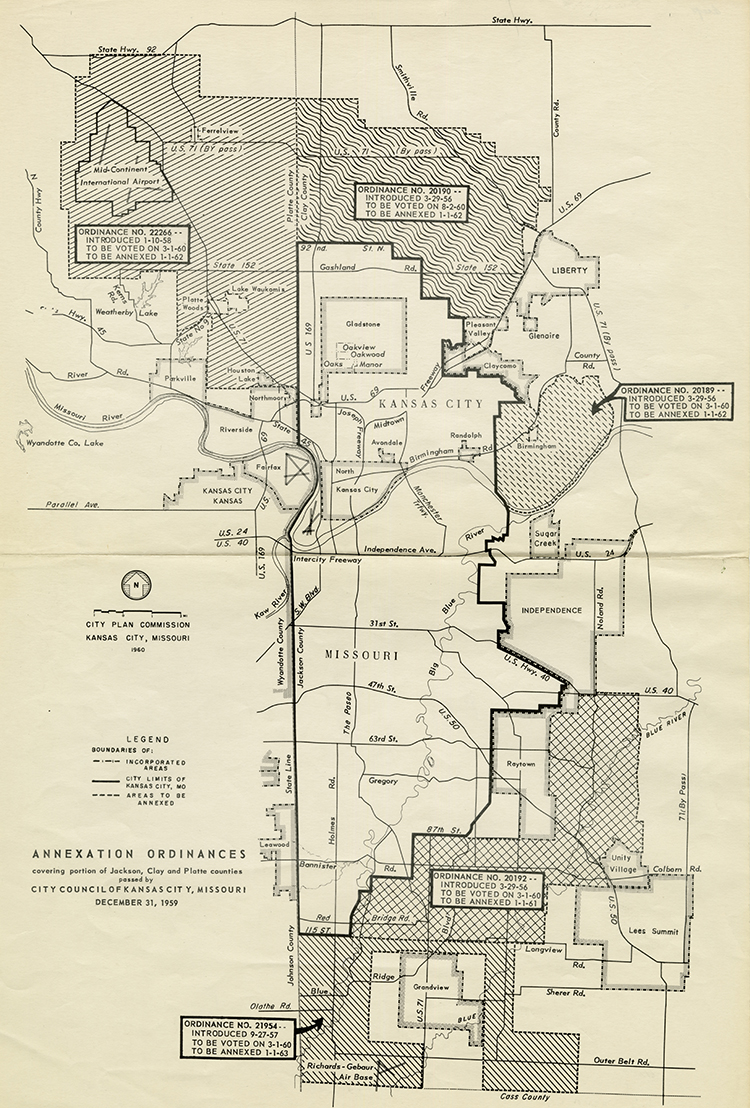

Anticipating further expansion attempts by the city and similar moves by other municipalities, some Clay and Platte county residents outside the newly annexed territory rushed to incorporate. With a wary eye on Parkville, Riverside incorporated in 1951. A year later, the town of Linden was chartered under a new name, Gladstone, and the tiny villages of Oakview, Oakwood, and Oaks were established along North Oak Trafficway. Pleasant Valley became a city in 1963. The message was clear: Incorporate or be swallowed whole.

Annexations nonetheless continued, extending into Platte County by the early 1960s. Kansas City wrapped itself around North Kansas City, as well as Platte Woods and Gladstone. With expansion of their city limits now off the table, the newly founded cities developed their own identities: close to KC, but with a distinct small-town feel.

As promised, development began north of the river. To ease traffic congestion for new residents, the old Chouteau railroad bridge was opened to automobiles. The new Paseo and Broadway bridges soon followed.

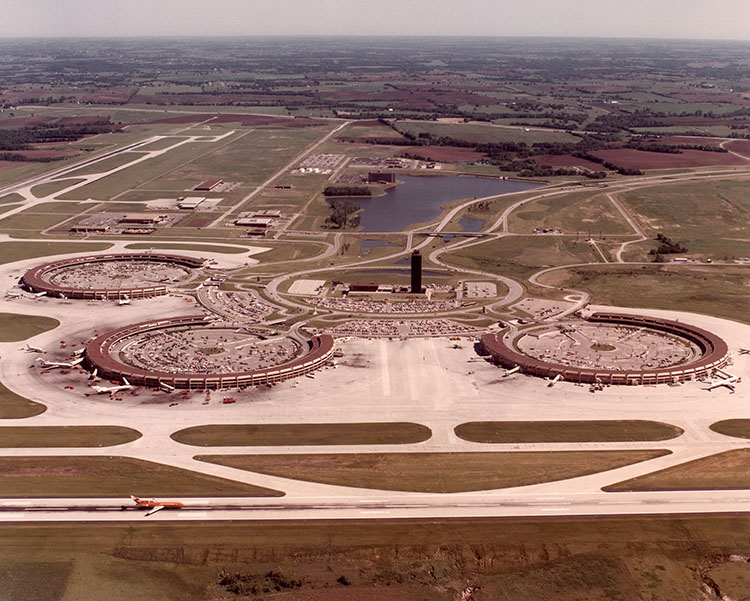

Still reeling from the effects of the disastrous 1951 flood, Cookingham envisioned a modern airport set away from flood prone rivers. With bad feelings over Kansas City’s annexation process in recent memory, many Clay County residents refused to sell their land for the project. Kansas City Stockyards President Jay B. Dillingham suggested that residents of his native Platte County would welcome the new airport. The frustrated city manager seized on the idea and Dillingham was proven right. Mid-Continent Airport, now Kansas City International Airport, opened its first runway in 1956.

Cookingham left Kansas City to become the city manager of Fort Worth, Texas, in 1959, remaining there until retirement. In a 1970 letter to The Kansas City Star, the former Clay County Self-Defense Committee chairman addressed Cookingham’s legacy. “L.P. Cookingham was a great city manager,” Randall Jessee wrote. “Some of us didn’t realize what an unusual manager he was until he left.” While comfortable acknowledging Cookingham’s vision for the city and his effectiveness, the former broadcaster remained irked by the issue of annexation. “I still think we were right in that opposition … annexation was one of the few mistakes Cookinham made,” Jessee said. “But there aren’t many Cookinghams. We haven’t had one since.”

Submit a Question

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.