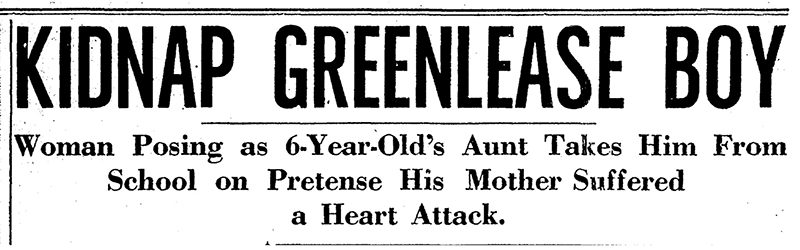

This infamous kidnapping and murder in Kansas City led to a hunt for the missing ransom

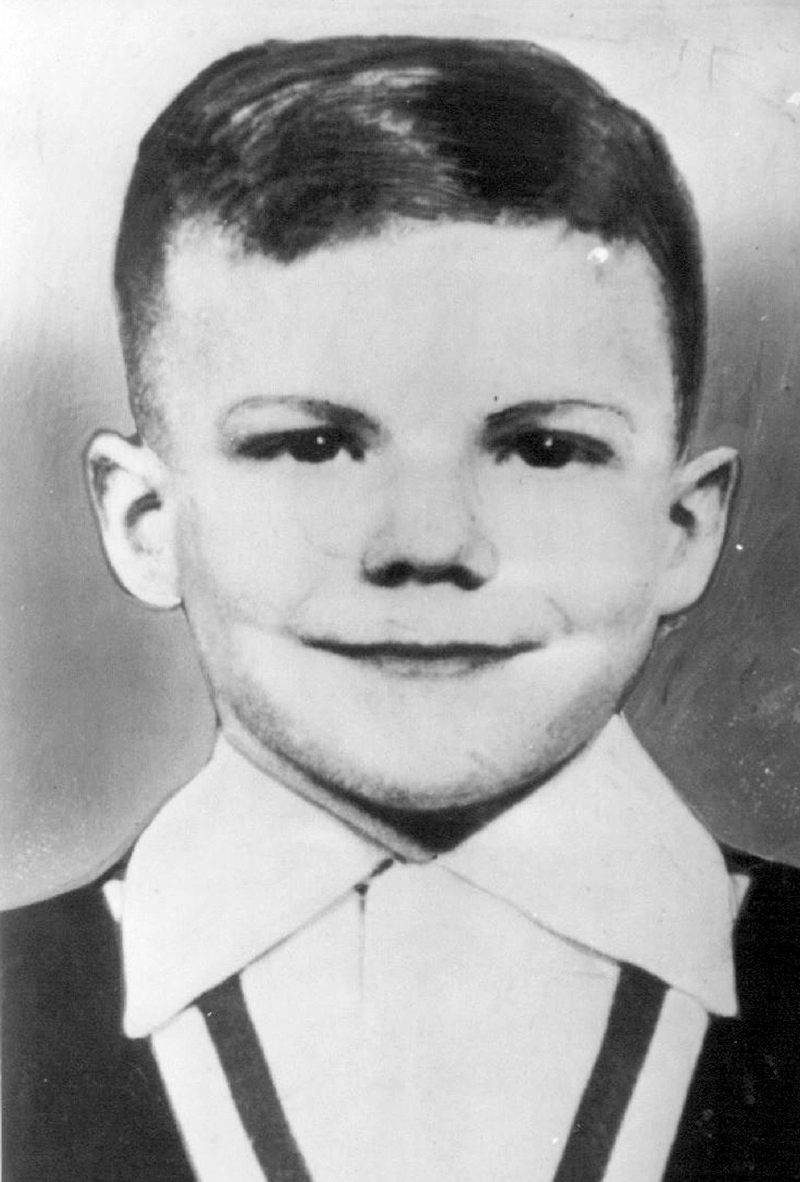

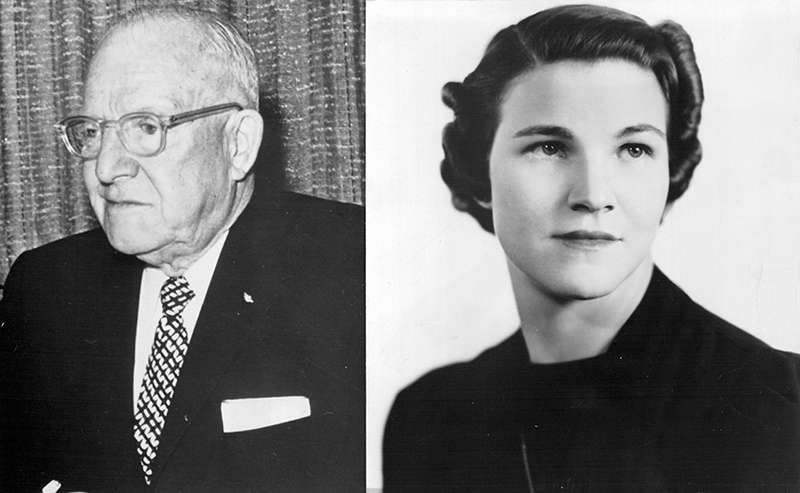

The 1953 abduction and murder of six-year-old Bobby Greenlease stands as one of Kansas City’s most notorious crimes. Bobby, the son of wealthy Cadillac dealer Robert Greenlease, was taken from Notre Dame De Sion School by two grifters, Carl Austin Hall and Bonnie Heady, in a cold-blooded kidnap-for-ransom plot.

On the morning of September 28, 1953, Heady posed as Bobby’s aunt claiming his mother had fallen gravely ill and needed him at the hospital. Trusting her story, the school staff allowed Heady to leave with the boy.

The kidnappers demanded $600,000 — just over $7 million in today’s dollars and the largest ransom in U.S. history at the time — but had no intention of sparing the boy, whom they killed shortly after taking him. More than half the ransom money later disappeared, adding to the crime’s infamy.

Reader Charles Ballew, like many others, was captivated by the case and reached out to What’s Your KCQ? to ask: “When was the last time any of the Bobby Greenlease ransom money showed up?” This question opens a window into the chaotic days and weeks after the crime, involving crooks, mobsters, and corrupt cops.

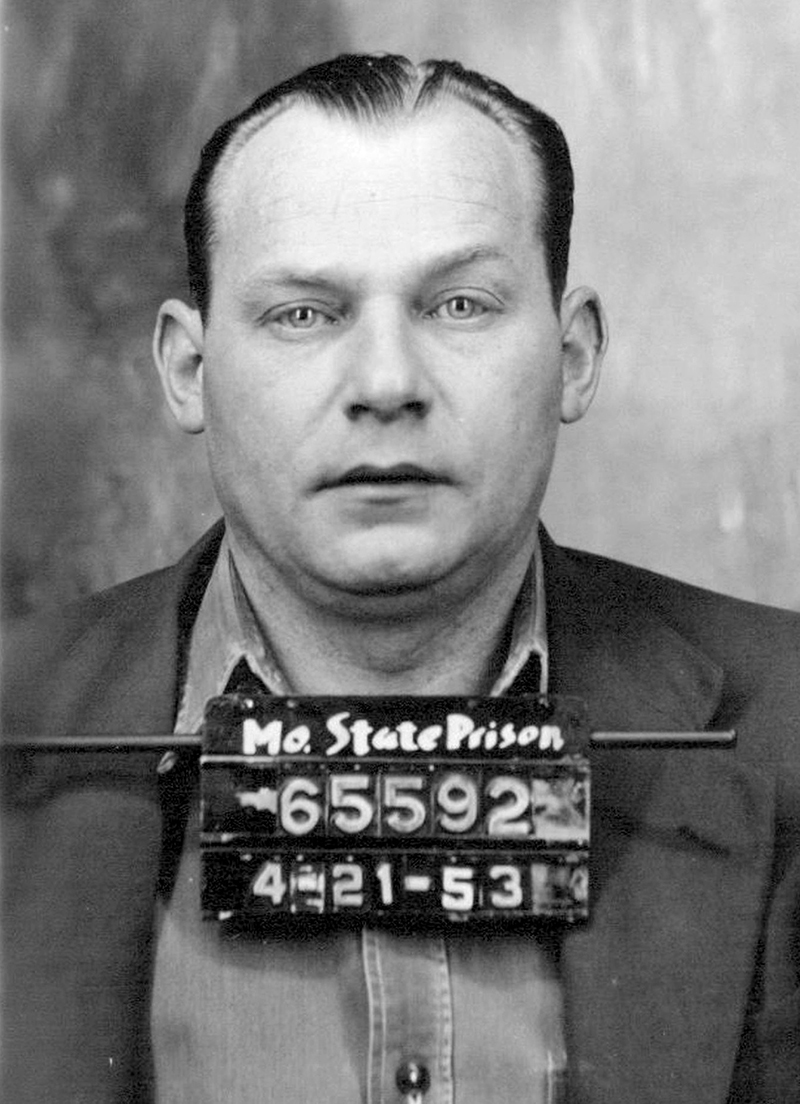

Carl Hall had schemed the kidnapping while serving time in the Missouri State Penitentiary for a string of taxicab robberies. He had been military school classmates with Robert Greenlease’s oldest son Paul and knew of the family’s wealth. Upon his release from prison, he found a willing partner in Bonnie Heady, a barfly and prostitute from St. Joseph, Missouri.

Robert and Virginia Greenlease learned of their son’s abduction the morning of September 28, when his school called the house to check on Virginia’s well-being. That evening, police intercepted the first of several ransom letters demanding $600,000 for the boy’s return.

The drop-off took place on October 5. As instructed, representatives for the Greenlease family left a duffel bag containing $600,000 in $10 and $20 bills next to a bridge on Lee’s Summit Road in eastern Jackson County. Waiting nearby, Hall retrieved the ransom and fled with Heady to St. Louis in a rented car.

Hall’s reckless behavior and heavy drinking over the next 48 hours would ultimately lead to their arrest.

After securing an apartment, Hall left an inebriated Heady in search of a drink and a different kind of female companionship. Carrying the ransom money in two suitcases, he hired a taxi driver and pimp named John Oliver Hager, an ex-convict, to arrange a date with prostitute Sandy O’Day.

Going by the alias Steve Strand, Hall spent the next several hours drinking with Hager and O’Day in a bar and later at a motel. Strangely cavalier around his new companions, he gave Hager $2,500 for safekeeping and to purchase for Hall new clothes and a briefcase.

The next morning, to throw law enforcement off his tracks, he paid O’Day $1,000 to fly to Los Angeles to mail a letter to his lawyer in St. Joseph. Hall also confided in Hager and O’Day that he was an ex-convict and drug addict and asked if Hager could procure morphine and false identification.

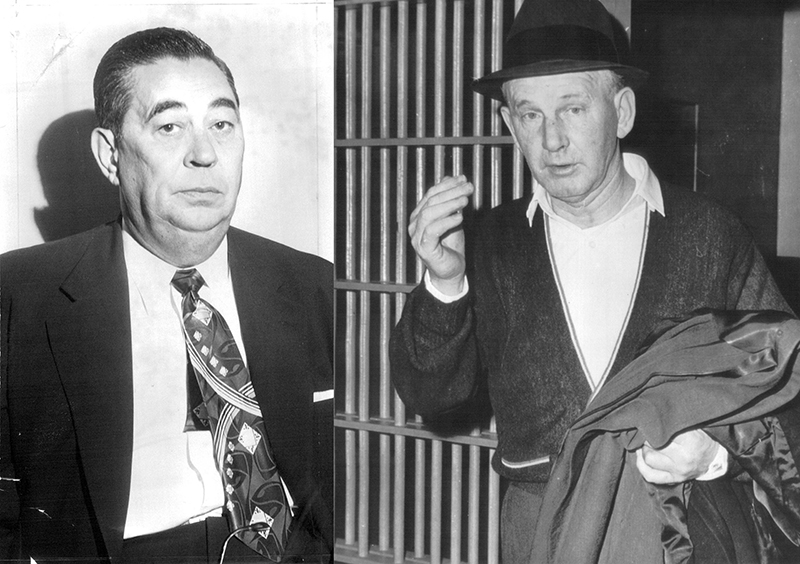

It’s unclear whether Hager suspected Hall of being the Greenlease kidnapper, but he was suspicious of the ex-convict flashing a lot of cash and saw an opportunity to get his hands on some of it. He alerted his cab company boss, local gangster Joe Costello, who tipped off an old friend in the St. Louis police department, Lt. Louis Shoulders.

That evening, while staying at an apartment that Hager had secured for him, Hall responded to a knock at the door. Expecting Hager, he was instead confronted by Shoulders and Patrolman Elmer Dolan.

Claiming to investigate a gun complaint, Dolan detained Hall while Shoulders searched the apartment and suitcases. “The jig is up,” muttered Hall when the officers discovered the money.

The two arrested Hall and accompanied him to a waiting, unmarked police car. Hall later testified that he saw an unidentified third man in the hallway outside the apartment, whose identity only became pertinent later.

Under questioning, Hall confessed to the kidnapping and implicated Heady – both eventually admitting their guilt in the killing of Bobby Greenlease. Kansas City courts tried and sentenced them to death. On December 19, 1953, fewer than three months after their crime and capture, they were executed together in a gas chamber at the Missouri State Penitentiary.

MISSING RANSOM

After Hall’s arrest, less than half of the ransom was recovered from his confiscated suitcases. The FBI launched a formal inquiry into the missing $304,000 and published a list of serial numbers of the missing bills.

Hall insisted he had around $592,000 in his possession at the time of his arrest. However, after learning he had purchased a shovel and garbage cans from a local hardware store, investigators initially believed that he had buried the missing ransom. Under questioning, Hall admitted to driving around looking for a secluded spot to bury the money, but claimed to have abandoned the plan.

News of the missing ransom caused a public fervor with citizens and reporters joining law enforcement in searching sites where Hall or Heady might have stashed the money. FBI agents in St. Louis scoured the muddy banks of the nearby Meramec River. Authorities in St. Joseph searched Heady’s home and property, where they discovered Bobby’s grave.

Investigators eventually turned their attention to the arresting officers, Shoulders and Dolan. They became suspects when it was discovered that they didn’t have the money-filled suitcases with them when they first arrived at the precinct station to book Hall, as they had filed in their report and testified to a federal grand jury.

Once the hero who captured the Greenlease kidnappers, Shoulders was indicted for perjury on December 30, 1953, and sentenced to three years in prison. Dolan received two years.

The first bunch of missing ransom bills turned up in various cities in Michigan and Indiana beginning in November 1953. Over the next three years, a total of 115 missing bills or $1,690 were recovered from circulation, mostly in the Chicago area but as far away as Florida and Utah.

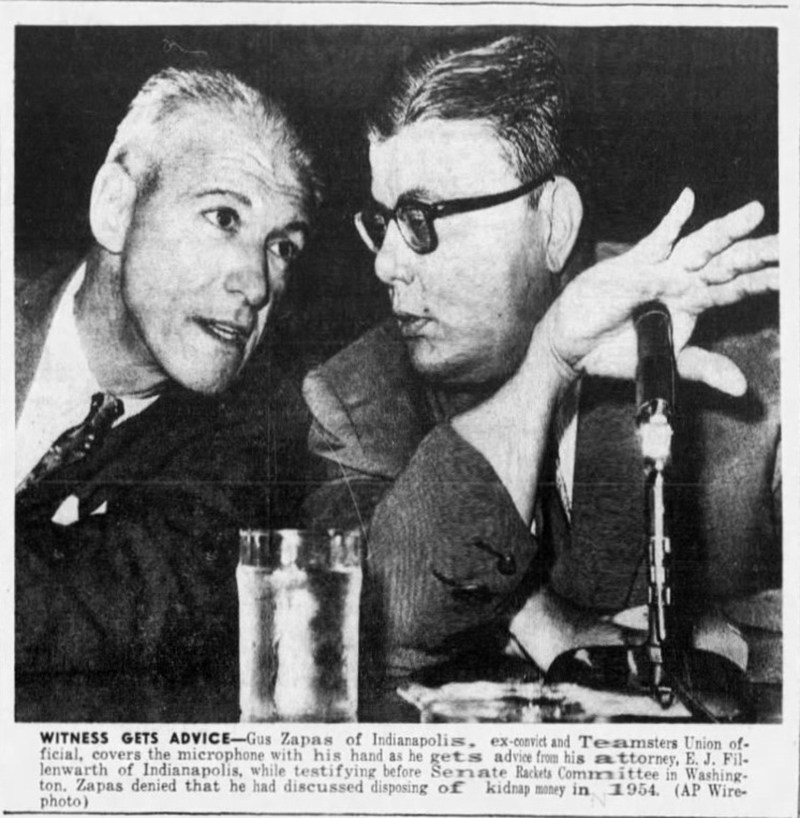

In 1958, the Greenlease ransom came up in the Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management. Federal agents had previously keyed in on Indianapolis Teamsters Union official Gus Zapas as a suspect in fencing the stolen money.

Nineteen days after officers apprehended Hall and Heady, Zapas was arrested in Chicago with two St. Louis crooks after an alleged meeting to discuss the laundering of a large sum of money. However, under questioning from committee counsel Robert F. Kennedy, and while his Teamsters boss, Jimmy Hoffa, looked on, Zapas denied any connection to the missing ransom.

A break in the case came in 1962 when Costello and Shoulders died of heart ailments within six weeks of each other. With no fear of retribution, Dolan confessed to the FBI that Costello was the unidentified man that Hall had seen in the corridor following his arrest, and who had conspired with Shoulders to steal the money. In exchange for his cooperation, President Lyndon Johnson granted Dolan a full pardon.

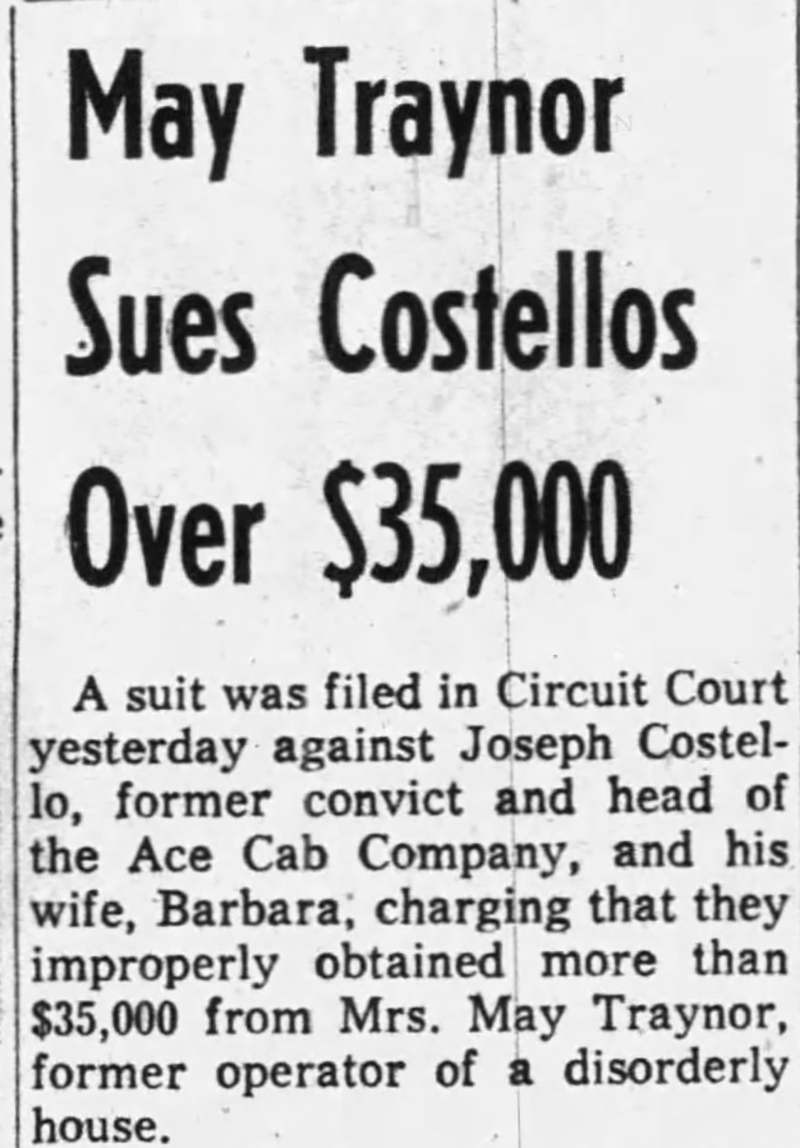

How Costello disposed of the ransom remained a mystery. One theory was that he laundered the money through a St. Louis brothel owner, May Traynor, to repay a large debt that he owed her. Traynor was purported to be Costello’s aunt by marriage, and he received loans from her to bankroll his taxicab company.

In 1961, after a falling out with her nephew, two assailants beat and shot Traynor in her home. Before dying from her injuries, she told police that “Joe Costello sent them.”

The prevailing theory by law enforcement was that the missing ransom likely passed from Costello to St. Louis mob boss John Vitale. The FBI suspected that Vitale moved the money through his mob associates in Chicago, possibly using carnivals and circuses to introduce the bills back into circulation.

The carnival connection gained traction in the press when it was revealed that some of the recovered bills were found in Midwestern towns where carnivals had recently visited.

In the decades to follow, as the Greenlease kidnapping-murder faded from the national spotlight, so too did the search for the missing ransom. With no new leads to follow, and the public no longer checking serial numbers of currency, the investigation went cold.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.