How a Kansas City work camp provided much-needed relief during the Great Depression

Oftentimes historical maps raise as many questions as they answer.

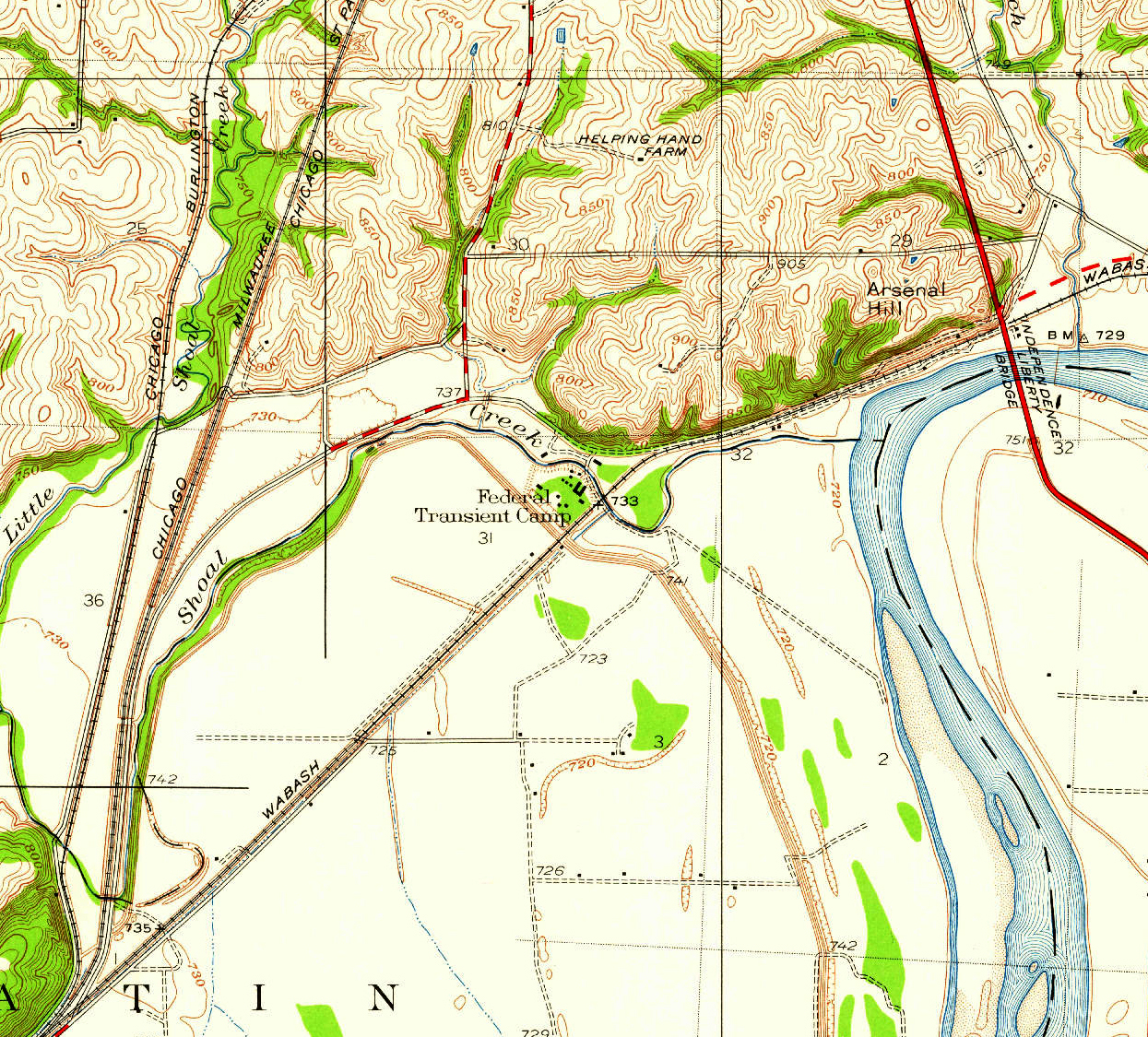

Recently, a local history researcher saw an interesting detail on a 1935 geological survey and asked KCQ: "On a 1930s map, I noticed a Federal Transient Camp located just west of where Shoal Creek entered the old River Bend area of the Missouri River. I assume this was a Depression-era camp similar to the one [where] the Joads camped in ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ I haven't been able to find any information regarding this camp. Can you provide any background?"

The Kansas City transient camp was indeed a product of the Great Depression. It was one of roughly 200 camps operated by the Federal Transient Service (FTS), a short-lived and often-overlooked New Deal agency that provided relief to the millions of unemployed and unhoused Americans.

In some ways the FTS camps were precursors to those depicted in "The Grapes of Wrath," yet by the time John Steinbeck began writing about Dust Bowl refugees in California, the FTS had been dismantled, and those it served had largely been abandoned.

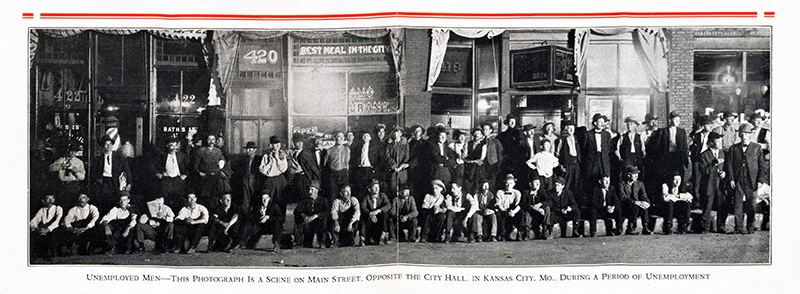

The idea for a transient camp arose locally in 1933, during the fourth and arguably worst year of the Depression. Nearly a quarter of all Americans were unemployed and some 2 million were homeless. Many, like Steinbeck’s Joad family, took to wandering the country in search of work.

Since the 1870s, Kansas City had had a sizable transient population. In times of economic stability, itinerant laborers were essential to seasonal work like the Midwestern wheat harvests. In times of depression, however, transient men were scorned as tramps, hobos, and bums.

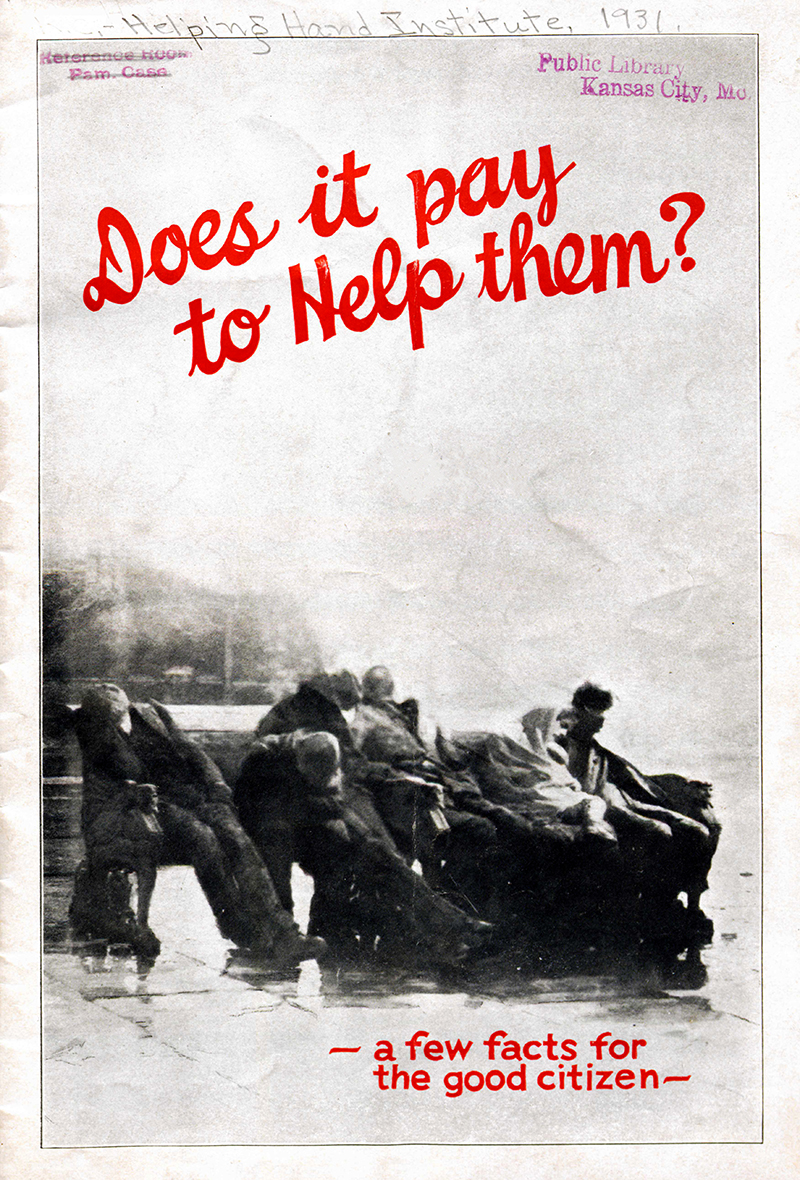

As the Depression worsened, vagrancy arrests soared and local charities, such as the Helping Hand Institute, reported a nearly threefold increase in their caseloads.

While many locals were loath to see relief funds go to nonresidents, pubic opinion was softened by the growing presence of entire families among the transients.

ESTABLISHING THE TRANSIENT FARM

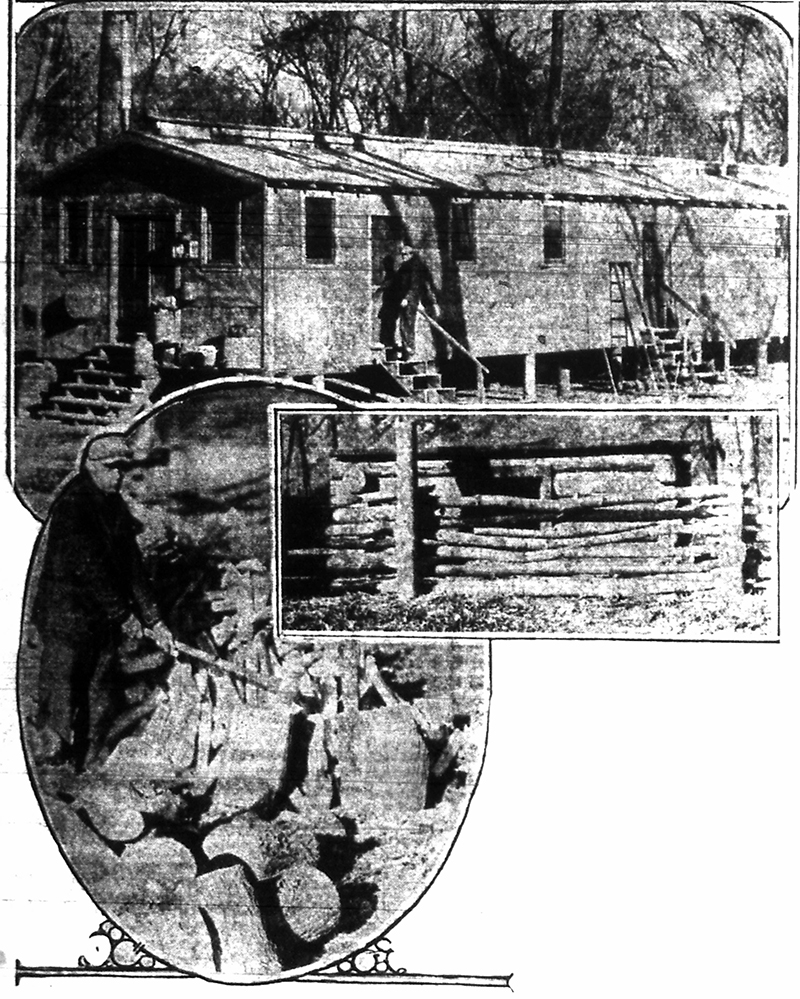

The Helping Hand advocated the establishment of a farm that would supply transients with work, shelter, and food. William Volker, a local businessman and philanthropist, liked the idea, and in July he donated a 350-acre tract of Clay County farmland to the institute.

At the same time, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration was preparing its own intervention. Few states had bothered to even apply for federal transient relief funds, and by late 1933, a Federal Transient Service was established and authorized to directly administer relief through local bureaus.

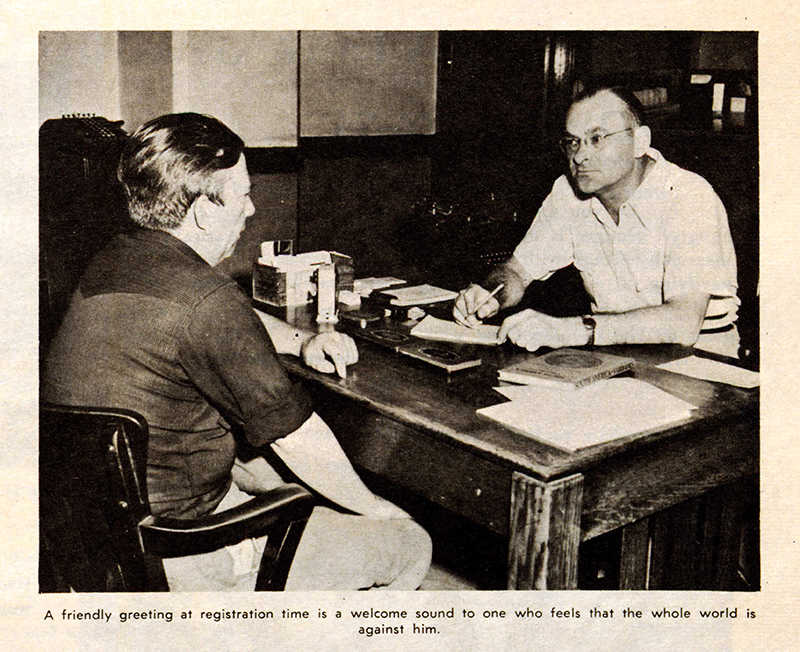

The Kansas City Transient Bureau began by interviewing transients with the goal of re-establishing contacts and returning them to their former home where they would have the opportunity to register with the local Civil Works Administration.

Unsurprisingly, returning transient residents to homes across the country was not feasible in most cases. Temporary shelters were thus established in Kansas City for families and unattached women, while unattached men could join the federal transient camp.

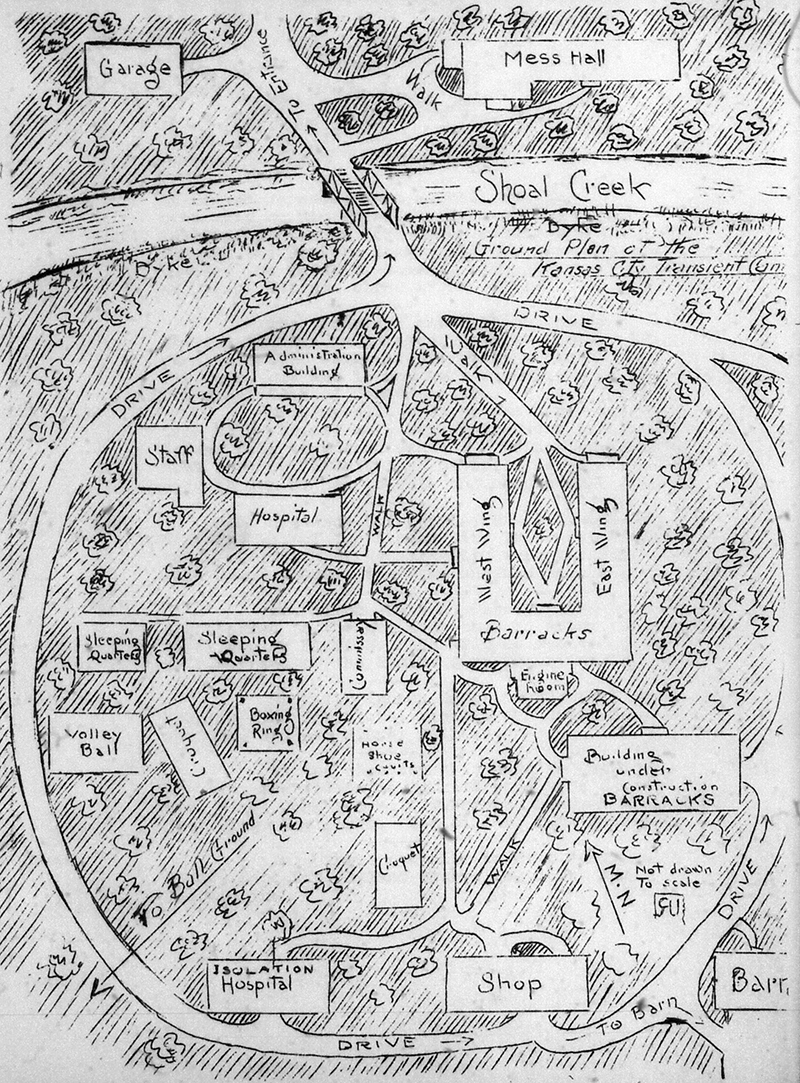

For the establishment of such a camp, Volker leased 175 acres of the Helping Hand Farm to the government, which quickly erected barracks to accommodate 100 men.

LIFE AT THE FARM

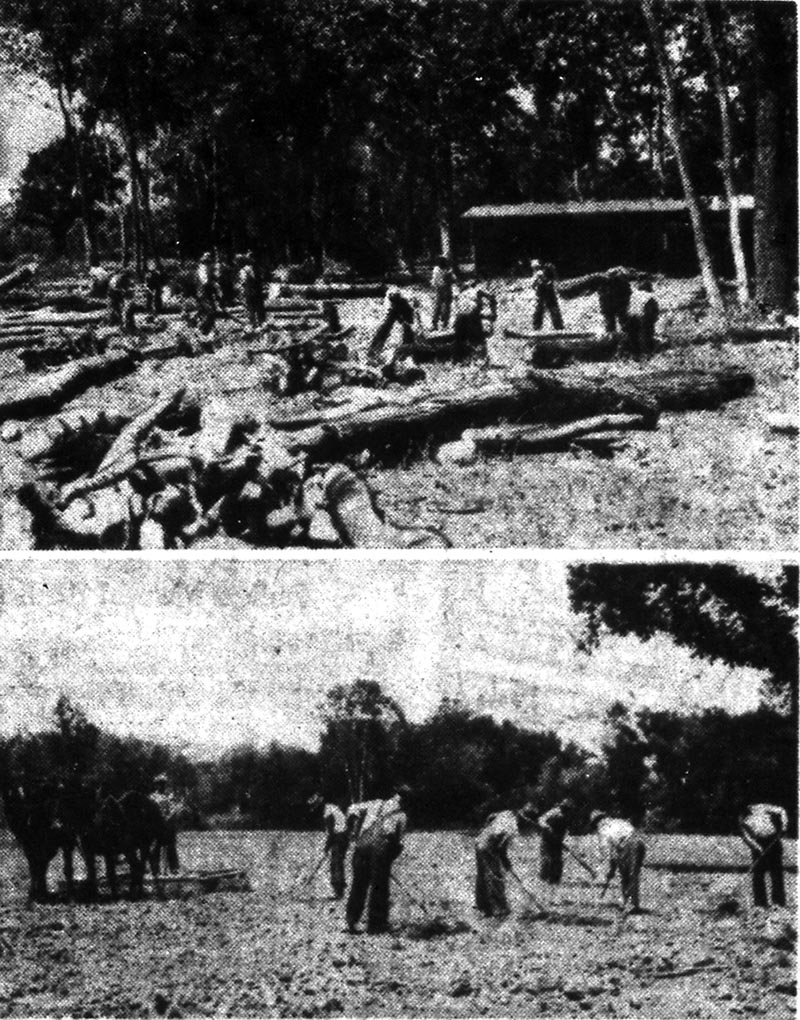

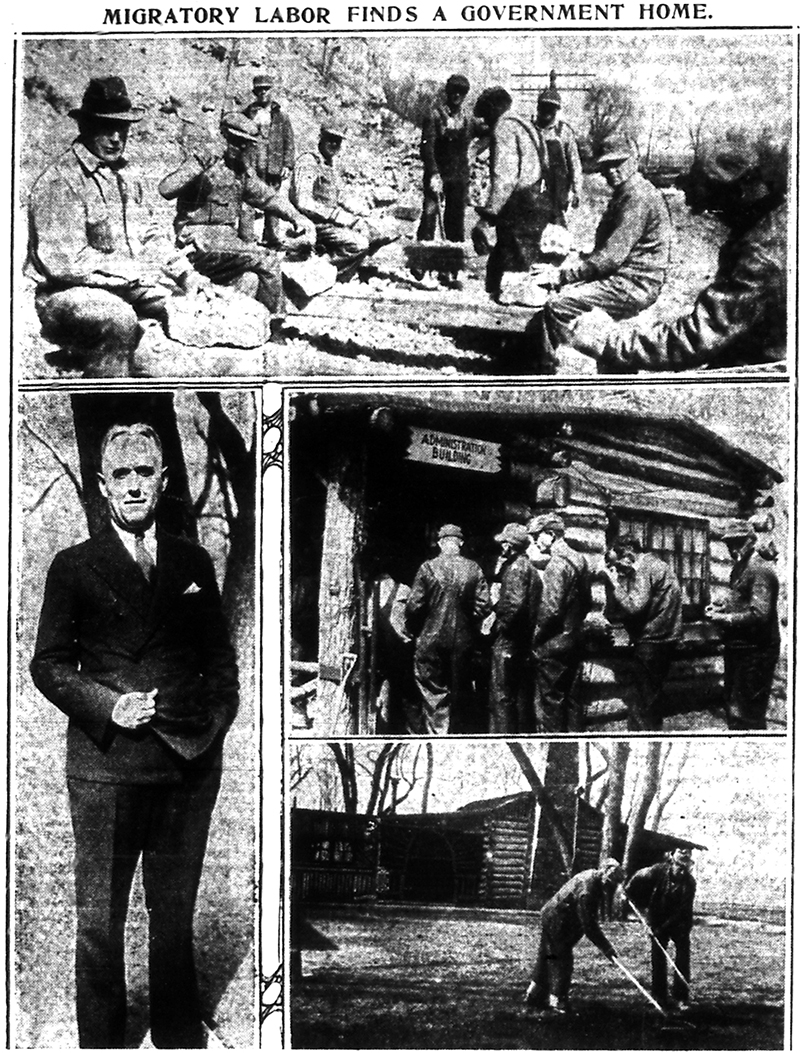

Men in the camp worked 30 hours per week for a pay of between $1 to $3. Their duties were primarily confined to the camp itself, split between crews which oversaw the farm, laundry, kitchen, quarry and woodshop, to name just a few. Outside of working hours, they also took frequent advantage of the boxing ring, baseball diamond, basketball court, and library.

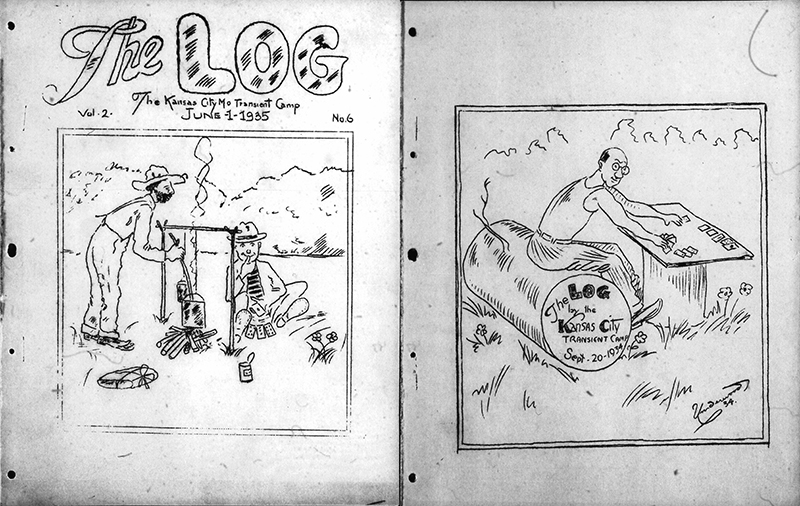

Some men even participated in life outside the camp. Adrian Suarez took courses at William Jewell College, while Roy Jones trained as an electrician in Kansas City, and John Rolland preached weekly in a small Liberty church. Such activities were chronicled in the camp magazine, "The Log," alongside poetry, witticisms, and a sports section.

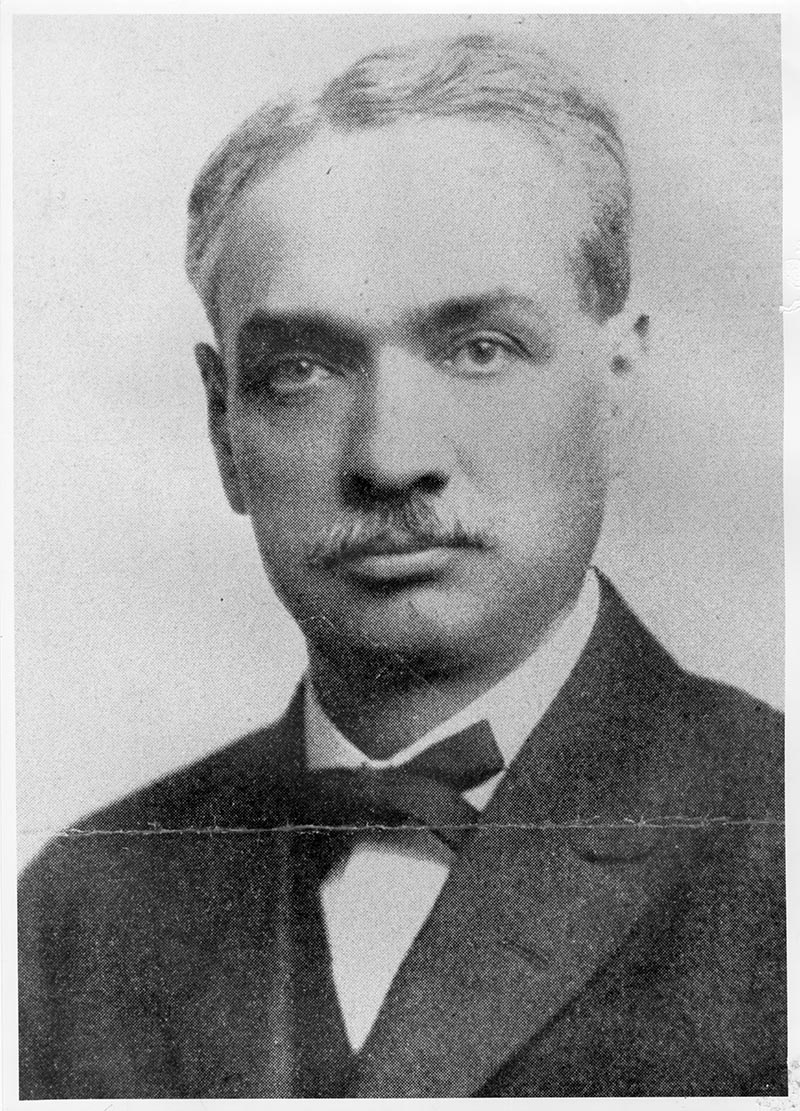

Five superintendents came and went over the camp’s first 10 months. The sixth to take charge was Romulus Bruce Church, a well-liked former professor of philosophy and a steadfast advocate of the transient program. Church was proud of the work being done by the FTS, and often invited journalists and university students to visit his camp.

DECLINE OF THE CAMP

The federal camps and shelters were undeniably effective in reducing the number of unemployed Americans wandering the country. Despite this, by early 1935 the FTS found itself on shaky ground.

The Emergency Relief Act of that year brought about more expansive work programs like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and left the continuance of existing relief agencies to the discretion of President Roosevelt.

Transient Service officials, however, felt that the value of their work was self-evident and were outwardly unconcerned. Church, for one, predicted that the FTS would continue for at least another decade, and that Kansas City would soon organize a second camp.

The men in the camp were also optimistic. A June flood had forced their temporary evacuation, but when they returned, work was immediately resumed on increasing the camp’s capacity to 250.

The atmosphere of optimism around the FTS came to a sudden end in August 1935. Seemingly out of nowhere, Missouri’s relief director announced massive spending cuts and the imminent dissolution of the Kansas City Transient Bureau.

The head of the Bureau, Anna Tregemba, resigned from her now nonexistent position, followed soon thereafter by Church. A few weeks later, Washington announced that it would scrap the entire transient program and would register no new cases after Sept. 20.

In the camp, this news came as a total surprise. The July and August issues of "The Log" had been delayed by a shortage of mimeograph paper, and when the September issue was finally printed, readers found within the shortened volume an "Addendum" titled "Bad Luck!," explaining the publication’s delay and concluding with the resigned admission that "as far as we know, this will be the last issue of The Log."

WHAT HAPPENED TO TRANSIENT PEOPLE AFTER THE GREAT DEPRESSION?

Washington denied that it was turning a blind eye to the plight of the nation’s transient population. Their plan was for "employable" men from the camps to be absorbed into local WPA projects.

However, only those registered with the FTS before September 20 were eligible, leaving new arrivals to fend for themselves as Missouri entered what was then its coldest winter on record.

Those deemed by the WPA to be "unemployable" were sent "home" to be cared for by local welfare organizations. This policy continued despite studies showing that fully half of all registered transients had no settlement rights in the states that they had left.

Of those whose rights had not been voided, fewer than half had any homes or families to return to. In the months that followed, the number of vagrancy arrests once again soared, and officials in California and Florida issued warnings that incoming transients would be forcibly deported.

In 1935, nearly $1.5 million was spent in Missouri on transient relief. Four years later the figure totaled under $1,000.

Today the grounds of the old federal transient camp sit empty.

Very soon after the shuttering of the camp, its facilities were disassembled and given to the state for a 1,050-acre prison labor farm in southern Boone County. The Helping Hand continued to operate a farm in Clay County for nearly 20 years, until that land too was sold to private owners.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.