How did Kansas City become Barbecue City, USA? KCQ cooks up a delicious tale

When you think of Kansas City, you think of a – perhaps the – barbecue capital of the world. No matter the event, there’s a strong likelihood it will be marked by a backyard barbecue. This is especially true on the Fourth of July.

For this installment of What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between The Kansas City Star and the Kansas City Public Library, we respond to reader Marcia Hall’s question: Why is Kansas City associated with barbecue more than any other Midwest city?

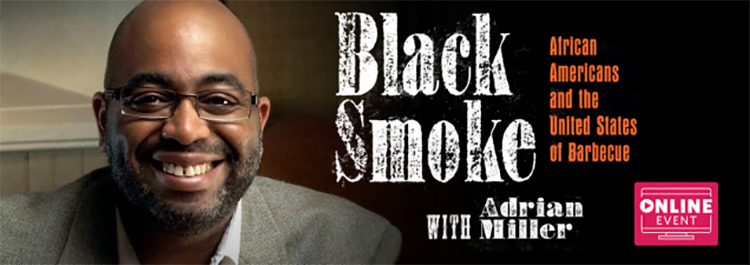

The question is a timely one. In addition to prepping for holiday cookouts, the Kansas City Public Library is hosting an online presentation by author and certified barbecue judge Adrian Miller on July 25 at 3:00 p.m. Miller will discuss his new book, “Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue,” and explain how Black pitmasters and restaurateurs – including some Kansas City legends – influenced this quintessential American cuisine. His presentation can be viewed live on KCPL’s YouTube channel.

KANSAS CITY-STYLE

The basics of Kansas City-style barbecue are easy to understand.

Spice-rubbed meat is slow smoked over a wood fire or coals. The region’s abundant forests of oak and hickory – both hardwoods favored by pitmasters – are a strong point in the city’s favor as a barbecue capital. In this way, it is similar to Memphis-style barbecue. However, we differ from other regional variations on two crucial points.

First, the variety of meats used. Where others focus primarily on beef or pork, practically anything’s on the menu in Kansas City. This is thanks to the next point on Kansas City’s barbecue resume – the stockyards and meatpacking industries that once thrived here.

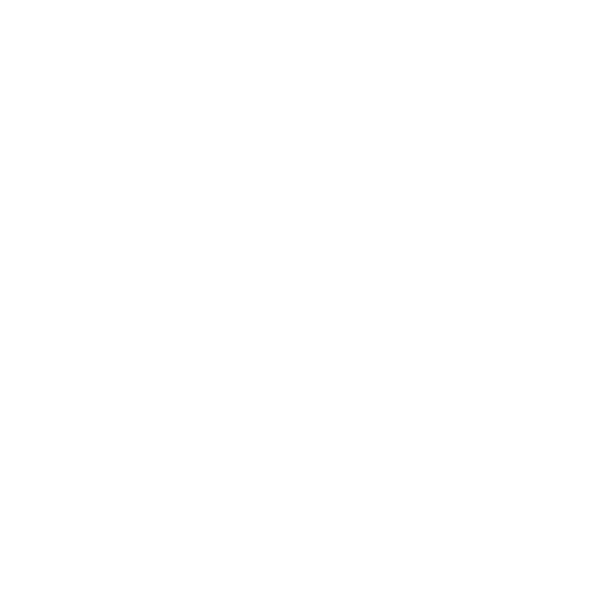

When the Hannibal Bridge opened in 1869, Kansas City was one of many upstart towns lining the Missouri River. The new bridge, the first permanent rail crossing over the river, positioned the city as the stopping point between western livestock breeders and eastern markets. How did Kansas Citians celebrate the event? With a barbecue, of course.

The Kansas City Livestock Company was established in 1871 to take advantage of the booming industry. By 1950, over 4 million head of livestock were being moved through the city every year.

In 1980, the connection between the historic stockyards district and Kansas City’s signature style was institutionalized with the first annual American Royal World Series of Barbecue. The competition, now in its 41st year, is the largest barbecue competition on the planet.

Meatpackers and butchers were often left with less desirable parts (ribs anyone?), providing a source of cheap product to anyone willing to make use of them. There are even stories of early pitmasters raiding the garbage outside the packing plants and butchers for discarded cuts.

This brings us to the next distinction in Kansas City-style barbecue – the sauce. Where Memphis-style sauce is thin, spicy, and served on the side, we’ve developed a taste for thick, tomato-based sauces, sweetened with brown sugar or molasses and slathered onto the meat before serving.

THE BARBECUE KING OF KANSAS CITY

One thing that all regional styles have in common is the contribution of foodways pioneered by and passed down to the descendants of Black Southerners. The Great Migration, the massive population shift of African Americans out of the South and into northern and Midwestern cities in the early 20th century, helped accelerate this culinary evolution. These new arrivals came seeking work and business opportunities, hoped for a better life for their children, and in the process, gifted us with our signature style of barbecue.

The relationship between the Great Migration and the development of Kansas City barbecue is perfectly encapsulated in the story of King Henry Perry.

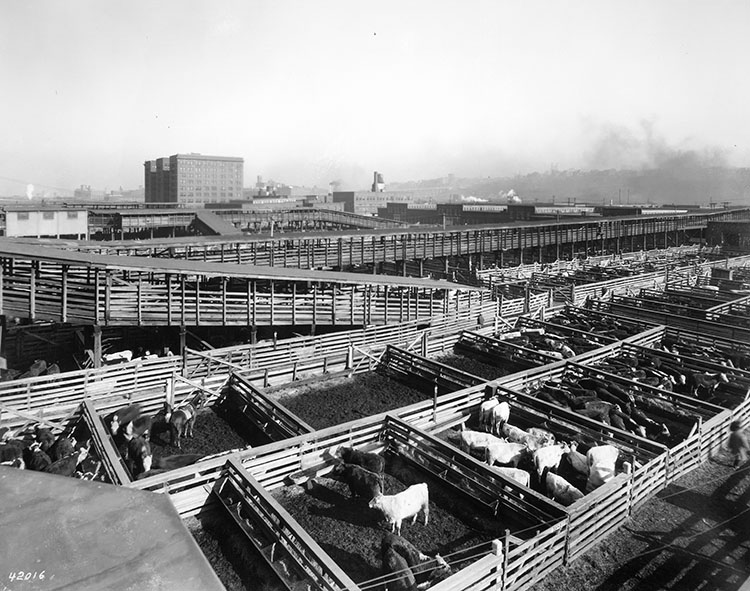

Born in Tennessee in 1875, Perry worked as a cook aboard Mississippi River steamships, where he began to develop his craft. In keeping with the Memphis barbecue style, those who tasted his sauce described it as thin, vinegar-based, and so heavy on the cayenne pepper that his customers often winced. He rambled about the Midwest, spending time in Chicago and Minneapolis before arriving in Kansas City in 1907. First working as a porter in a Quality Hill saloon, it wasn’t long before Perry had taken to selling barbecue from a stand in the city’s Garment District.

By 1911, Perry had relocated to a tent at 18th and Vine streets, where he tended a brick-lined pit dug into the ground and already called himself the Barbecue King. Speaking with a Kansas City Star reporter, he described having a hard time making barbecue pay the bills. He admitted, “Lots of times I just throw up my hands and quit altogether and get me a job at $8 or $10 a week.” But, he continued, “I can’t stay away from it. Every time I drift back to this little old tent and start a fire under some kind of a piece of meat.”

Perry pitched his tent where his barbecue would sell. In time, he gave up finding other jobs, settling into brick-and-mortar locations, first at 19th and Vine and later at 19th and Highland. By the time of the 1930 Census, Perry reported the following: “Occupation – Barbecue; Industry – Barbecue.” The King had claimed his realm.

Despite staying close to the heart of Kansas City’s vibrant Black community, he developed a following that crossed racial barriers. In 1932, a reporter for The Call wrote, “With a trade about equally divided between white and black, Mr. Perry serves both high and low. Swanky limousines, gleaming with nickel and glossy black, rub shoulders at the curb outside the Perry stand with pre-historic Model T Fords.”

Word of King Henry’s reign spread throughout the region. Much has been made of author Calvin Trillin’s boasting of Kansas City barbecue in national publications in the 1970s and ’80s, which inspired curious east coasters to have ribs and other dishes shipped cross country, but the buzz was nothing new. In a 1917 letter printed in The Topeka Plaindealer, a well-traveled and hungry fan wrote to Perry, “Dear Sir – received by parcel post just before leaving Chicago a package of your delicious meats. … I am enclosing money order here for three dollars. Please deduct postage and send me the rest in ribs, and you may put in some mutton. Send this parcel post to Clarence R. Brown, 165 Broadway, New York City … Please send this out at once, as I want to introduce your ribs to Broadway.”

In 1920, to thank the community for his success, Perry hosted a free barbecue at which he is said to have served up 1,000 free meals. In recognition of his generous act, Kansas City marked July 3, 2020, as Henry Perry Day on the cookout’s centennial.

THE PERRY METHOD

As business prospered, Perry hired help. Notably two brothers from Texas.

When Arthur Bryant arrived in 1931, his older brother Charlie was already established in Kansas City and learning the barbecue trade under Perry. Like so many other Black, southern transplants, the Bryants moved north to escape the poverty of their rural upbringing. Arthur had armed himself with a college degree but saw a future for himself here. He stayed, and Perry hired him.

Under Perry, the brothers learned his methods for smoking meats and for his not-so-Kansas City-style sauce. Charlie preferred Perry’s way – that is to say hot … very hot. Arthur disagreed. In a 1966 interview with The Star, Arthur recalled how customers would react to the Perry sauce. “You could tell it the way people frowned.” Arthur believed barbecue sauce should be “a pleasure.” But being below his older brother in the pecking order, the changes he had in mind would have to wait.

Another Perry disciple was a man named Arthur Pinkard. Born in Alabama in 1880, Pinkard had arrived in Kansas City by about 1917. He worked a variety of jobs at first but was eventually hired by Perry and learned his barbecue method. At some point, he became the pitmaster at Ol’ Kentuck Bar-B-Q, originally located at 24th and Forest and later at 19th and Vine. Pinkard was working there in 1946 when two other giants of Kansas City barbecue bought the business – George and Arzelia Gates.

Through Pinkard, the Perry tradition was passed on to the Gates family and Ol’ Kentuck eventually became Gates Bar-B-Q. Pinkard retired not long after the Gateses took over the business, relocated to St. Louis, and died there in 1963. Today, a photograph of Pinkard can be found in all Gates locations.

Henry Perry died in 1940 at age 66. According to his death certificate, his remains were taken to Osceola, Arkansas, on the banks of the Mississippi, the river along which he had learned his craft as a young man. His exact resting place there remains a mystery.

Perry left the business to his protégé. The rebranded Charlie Bryant Barbecue was moved to a larger space at 18th and Euclid. Charlie ran the business until retiring in 1946. It was time for Arthur to make some changes.

KANSAS CITY-STYLE EVOLVES

Arthur Bryant did not conceive of tomato-based barbecue sauce. In addition to the usual vinegar and spices, a recipe published in The Star in 1927 calls for one can of tomatoes, one small bottle of catsup, and a can of Spanish tomato sauce. Other sources have credited the popularization of tomato-based sauce to World War II rationing, when spices were difficult to find and pricey, but catsup and tomato sauce was plentiful and cheap.

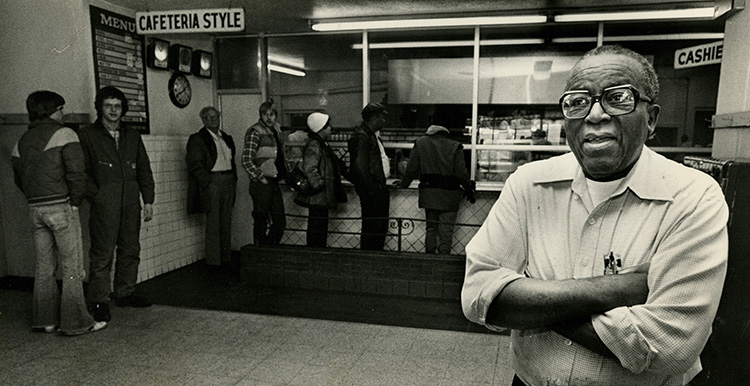

Whether or not Bryant experimented with tomatoes during the war years is unknown, but the old Perry sauce was one of the first things to go under his watch. He cut the cayenne pepper and made it sweet, “a pleasure,” as he was fond of saying. Years later, tomatoes were added to the recipe. Certain purists still reject tomato-based sauces outright, but his restaurant was onto something. The sauce served up at the renamed Arthur Bryant’s Barbecue became legendary and transformed Kansas City barbecue into what we know it as today.

He also improved the dine in experience for his customers – a bit. In addition to moving the restaurant to its present location at 18th and Brooklyn, he modernized the dining area and added air conditioning with the caveat that he never wanted to fully lose touch with the “old grease house atmosphere.” About the restrained redecoration, Bryant said, “That’s just not barbecue, not when you got them plush seats … you can’t get too fancy or you get away from what the place is all about.”

Because many early Black barbecue entrepreneurs operated wherever they could, often merely digging a pit and pitching a tent in a vacant lot or setting up in rundown buildings where the rent was cheap, the grease house atmosphere became synonymous with the authenticity of barbecue restaurants. The Gates family took a different approach.

Born in 1931, George and Arzelia’s son Ollie was just coming of age when the family purchased Ol’ Kentuck Bar-B-Q. He began learning the barbecue business while attending Lincoln High School. Later, he graduated from Lincoln University with an engineering degree and entered the U.S. Army. When George died in 1960, Ollie took over the family business, bringing an engineer’s eye for detail and military precision to Gates Bar-B-Q.

Unlike Arthur Bryant, Ollie Gates was willing to fully abandon the grease house image. Realizing that modern fast-food chains were his main competitors, he elevated the standards for every aspect of the business. Recipes were perfected to ensure consistency, his staff wore neat uniforms, the business was marketed in a way that no barbecue joint had been before, and Ollie insisted on clean and modern dining areas for his customers.

WORD SPREADS

While, again, Trillin did a lot to sell the world on Kansas City barbecue, others were spreading the gospel.

In 1923, Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium, then called Muehlebach Field, was built at 22nd and Brooklyn streets, just a few blocks from the city’s hotbed of Black-owned barbecue restaurants around the 18th and Vine community. The Blues, Monarchs, and Athletics baseball teams all played at Muehlebach. Later, the Royals and the Chiefs called the stadium home before moving in the early 1970s.

Radio broadcasters, newspaper reporters, and visiting teams couldn’t help but notice the smell of the barbecue smoke drifting into the stadium. The aroma was frequently mentioned over the air and included in writeups of the games. Of course, the out-of-towners invariably made the short walk over to barbecue Shangri-La. Kansas City’s place on the barbecue map was broadcast over radio frequencies and by newspaper presses across the Midwest.

LONG LIVE THE KING

Since 1972, the sports-barbecue connection has continued in the parking lot of the current home of the Royals and of the Chiefs, the Truman Sports Complex. Each fall when the Chiefs play at Arrowhead Stadium, thousands of tailgaters fill the air with enough smoke to keep game announcers singing the praises of Kansas City barbecue and to pay homage to the king.

Towering figures like the Bryant brothers, Arthur Pinkard, and the Gates family are not alone in their debt to Henry Perry. He left his mark on many of the city’s early barbecue restaurants and cooks. Through the many pitmasters out there – professional and novice alike – his tradition lives on. And because so many barbecue joints welcomed jazz musicians to entertain their clientele, the growth of Kansas City’s signature music was helped along by its signature food tradition.

Several factors combine to make Kansas City the barbecue capital that it is – the availability of hardwoods, the rise of the meatpacking industry, a signature sauce, vocal promoters. But it is the people, notably entrepreneurial Black Americans who made Kansas City their home and brought their Southern cooking traditions with them, that made the city the barbecue capital of the world.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.