A Hole with a Story - KCQ Investigages the Kessler Park Reservoir

During a recent visit to Cliff Drive in Kessler Park, a reader said, he noticed a turnoff near the west entrance to the scenic byway. He followed the road up a hill and was treated to a spectacular view stretching across the Missouri River into Clay County.

Continuing up, he noticed a line of trees at the top of the hill and decided to investigate. He found something peculiar – what seemed to be an abandoned and graffiti-covered, concrete swimming pool surrounded by an iron fence.

The reader asked What’s Your KCQ?, a collaboration between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library, “What is the concrete pit atop the hill, and why is it there?”

The answer to the first part of the question lies in the name of the road surrounding the hill: East Reservoir Drive. The basin is an old water reservoir. But why is it in a city park and, why was it abandoned?

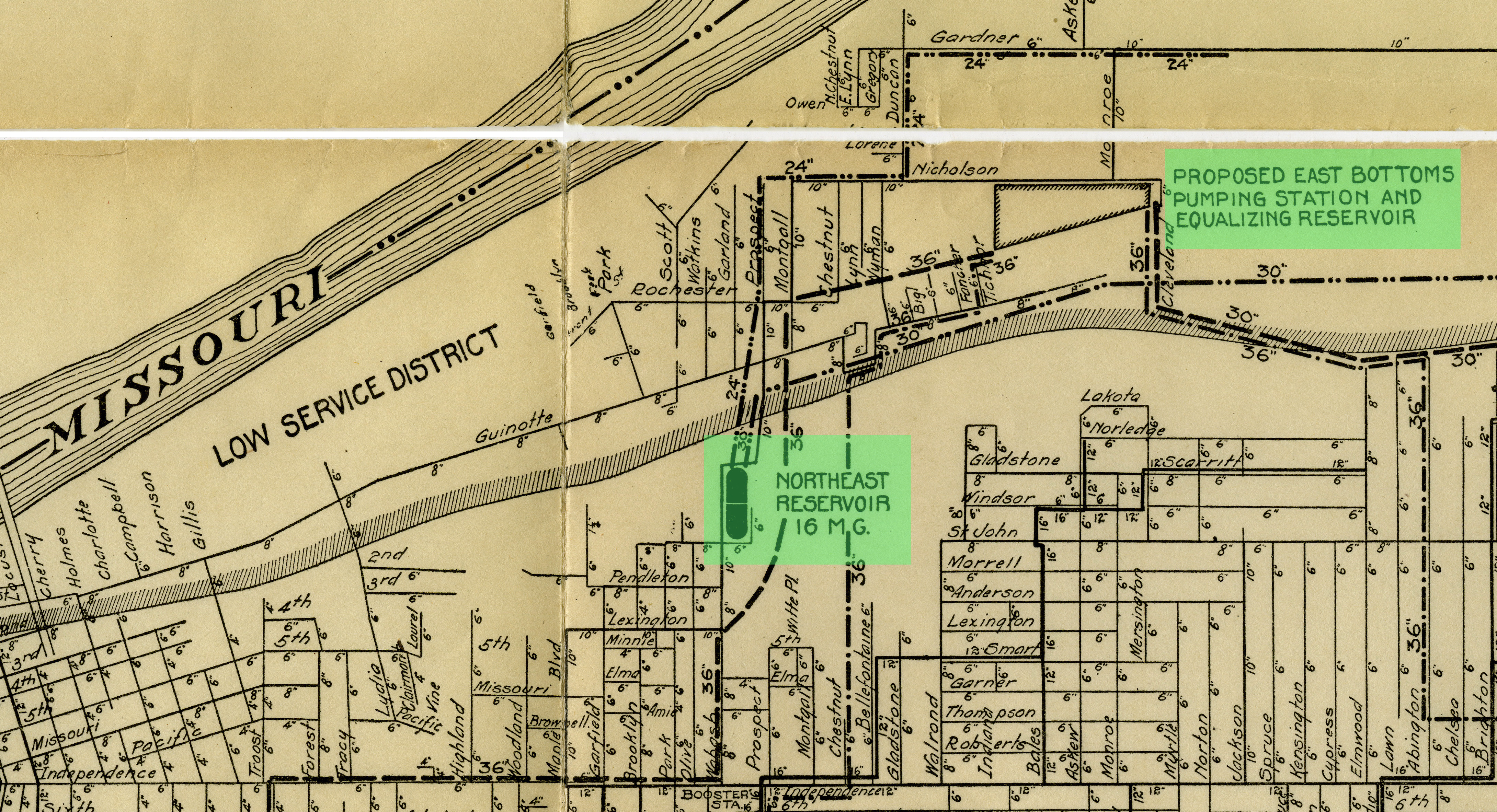

Kansas City’s adjacent Northeast neighborhoods were well established by the early 20th century, but industrial development to the north, in the East Bottoms, was just starting to boom. The area’s water was supplied by the Turkey Creek pumping station all the way across town in the West Bottoms. Rising demand and the expense of pumping all that water across the city began to add up.

So, in 1918, the Board of Fire and Water Commissioners approved a plan to create a new reservoir closer to the Northeast and East Bottoms districts.

With water usage much higher during the day, it was determined that filling a local reservoir overnight would ease the strain on the pumping system. Plans for the 17-million-gallon reservoir were drawn up, and the Board of Park Commissioners set its location in Kessler Park — then called North Terrace Park. Atop a hill, it would be hidden and unobtrusive to parkgoers.

The project was put on hold until the end of World War I, but construction got underway in 1919 and was completed the following year.

Rather than hauling away the tons of dirt removed from the hilltop, a plan was devised to wash it downhill to the southeast through a 6-inch pipe into North Terrace Lake. Park authorities welcomed the opportunity to fill what locals called Suicide Lake, whose 35-foot depths and steep rock ledges at its edges posed a danger to swimmers. It was also a notorious breeding ground for mosquitoes.

The dirt didn’t come close to filling it, though. North Terrace Lake endured in a compromised state, remaining an ideal mosquito habitat, according to newspaper accounts. In the 1920s, the Parks Department had the old lake restored.

When the hilltop reservoir was completed, a serious problem emerged almost immediately. It seemed to be leaking water. A lot of water. The flow downhill was so persistent that rocks, soil, and even trees began to cascade down onto Cliff Drive, causing a temporary closure.

The Parks Department blamed faulty construction. The Water Department insisted the reservoir was sound, blaming natural springs in the hillside. Landslides onto Cliff Drive were a big problem, but an even more dangerous threat loomed. If the reservoir truly was leaking, there was a small chance it could burst and send its 16,000 gallons of water spilling into the East Bottoms.

The task of tracking down the source of leak fell to Charles Foreman, the Water Department’s chief engineer. He treated the water in the reservoir with a lime solution, then tested the seepage from the hillside. But no trace of lime was found. Foreman had the basin drained and, while the leak slowed, it didn’t stop.

Foreman next had the basin filled to a depth of 3 feet and the waterline marked so the level could be studied to determine if it dropped beyond the rate of natural evaporation. The waterline was gradually raised and the study repeated at different intervals, hoping to pinpoint the location of a possible leak, but this, too, was inconclusive.

While some of the results suggested the basin wasn’t to blame, skeptics pointed out there hadn’t been a seepage problem on the hillside before its construction.

Eventually it became accepted fact that the reservoir was indeed leaking, but the source was never located. In 1920, some 122,000 gallons of water escaped down the hillside. By 1922, the rate had slowed to 17,000 gallons. City Engineer Robert W. Waddell hypothesized that the mysterious leak was gradually being filled in with sediment and would eventually be plugged. A tile drain system was installed in the park to manage the leak and combat erosion.

Fortunately, the Parks Department wouldn’t have to worry about the leaky basin for long. In 1926, a new Northeast pumping station with its own reservoir was completed in the East Bottoms. No longer would the area have to rely on the Turkey Creek station for its water supply. The old reservoir was drained and held in reserve by the Water Department for possible future use.

But the need never arose. Though ideas for use have come and gone over the years, the structure is yet to find its second life.

But plans are now in the works.

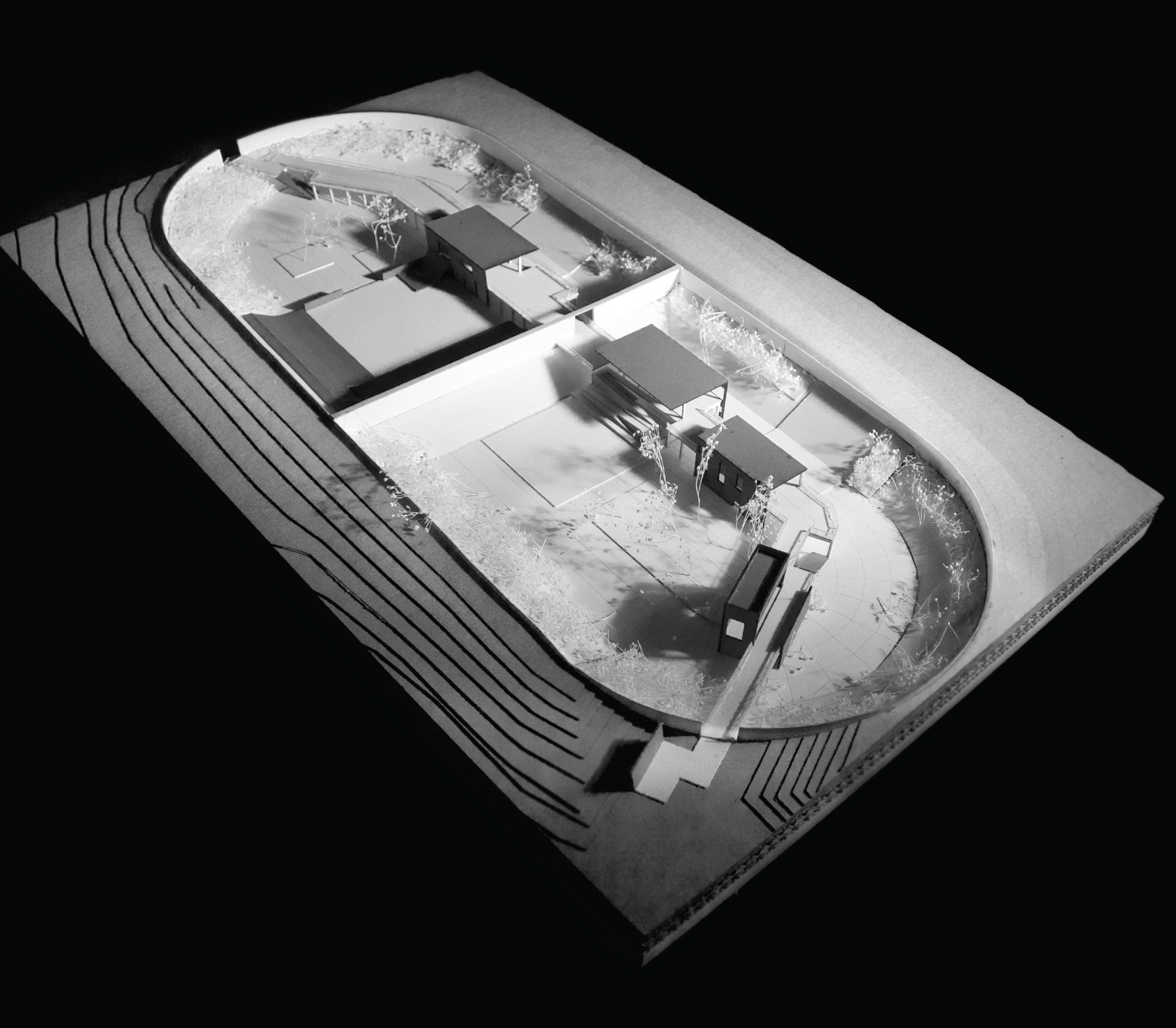

In 2014, the Kansas City Design Center, a downtown-based urban design program affiliated with the architecture and planning departments at the University of Kansas and Kansas State University, began developing adaptive reuse strategies for the reservoir. Initially, plans to redevelop the site as a water and skate park, or as a “Living Link” — a community interaction, observation, and identity hub — were advanced.

Today, KCDC is in dialogue with community members and Kansas City Parks and Recreation to develop new reuse plans and determine the best possible future for the forgotten reservoir in Kessler Park.

SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.