The Chiefs … basketball team? KCQ explores the team’s once popular offseason pastime

Tyreek Hill may have departed for Miami, but Kansas City Chiefs fan may recall a 2021 video of the star wide receiver on the basketball court, celebrating his 27th birthday with a windmill dunk. Later that year, he was joined by teammates Chris Jones and Tyrann Mathieu (now with the New Orleans Saints), and others for a game of hoops to raise money for his Cheetah Scholarship fund.

A reader asked “ What’s Your KCQ?,” a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library, “How common is it for Chiefs players to play off-season basketball games?” Skittish fans might wonder further: What are the risks?

That unease is nothing new.

In 2019, quarterback Patrick Mahomes was recorded playing in a pickup basketball game at a local gym. The video went viral, prompting Chiefs General Manager Brett Veach to respond, “The Kingdom can rest assure that we have that under control: no more basketball for Pat.”

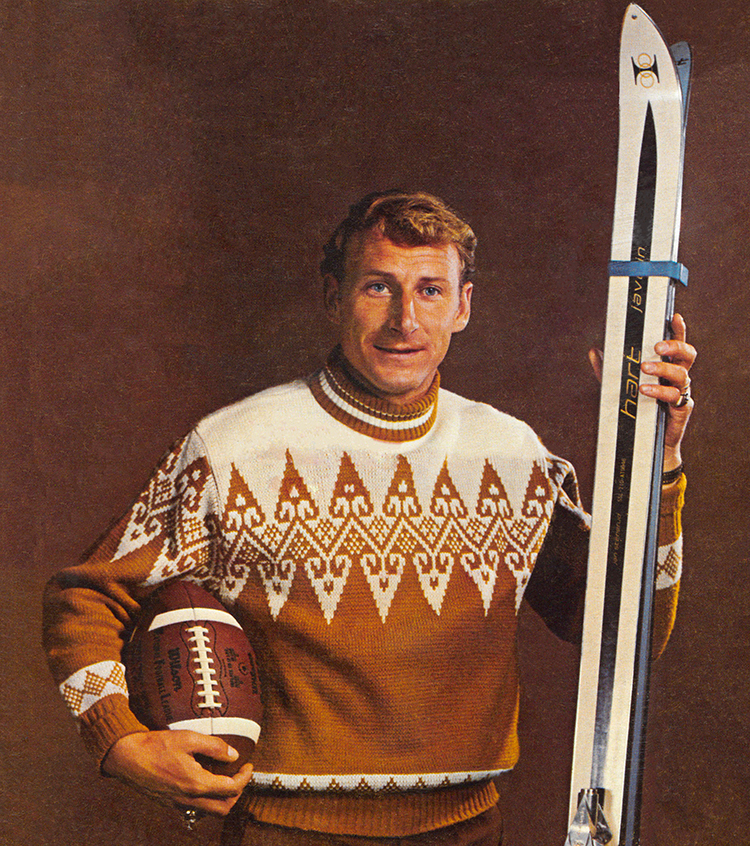

Earlier this year when New Orleans Saints running back Alvin Kamara worried fans by declaring his love of snowboarding, longtime Chiefs fans may have recalled Hall of Fame kicker Jan Stenerud’s fondness for downhill skiing – acquired as he was growing up in Norway.

On a larger scale, fans have nervously watched their favorite players compete in Olympic-style events and on obstacle courses on the popular television programs Superstars and SuperTeams. The concept debuted in 1973.

Today, standard player contracts forbid players from engaging in activities that “involve significant risk of personal injury.” Basketball, snowboarding, and skiing certainly have their dangers, but so do all physical activities, and most tend to be safer than football. Ultimately, pro athletes need to stay in shape year-round, so teams have learned to live with a degree of injury risk.

Be it for exercise or to raise money for charity, many NFL stars commonly engage in other sports after their seasons conclude. What may surprise some is just how organized offseason basketball was for Chiefs players at one time.

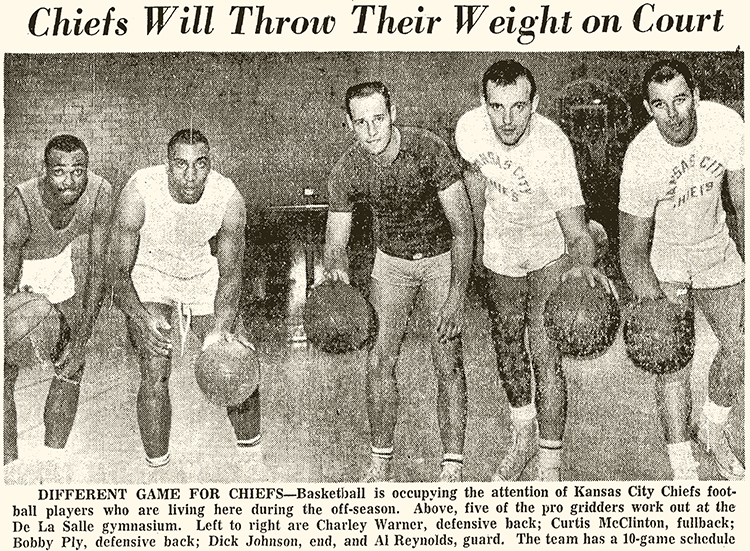

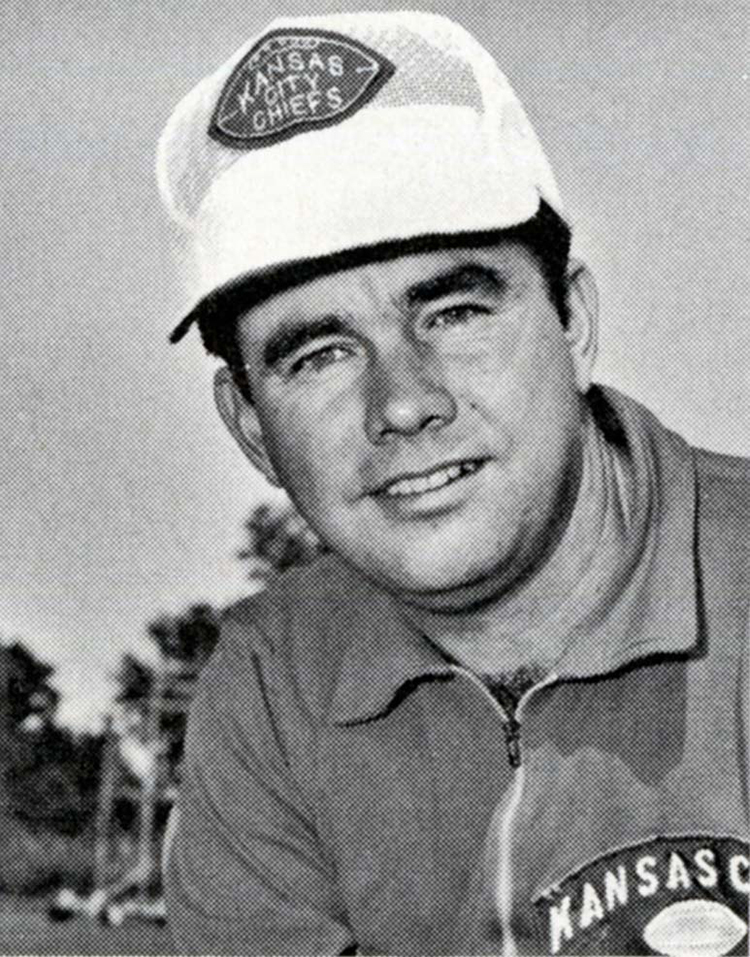

In 1964, the Chiefs were new to Kansas City, having relocated from Dallas the previous year. Following a disappointing first season in their new home, a handful of players started a basketball team for the club. The idea was not new, the San Francisco 49ers formed a basketball team in 1953, and the notion spread to other teams across the country.

In Kansas City, the basketball exhibitions helped build the Chiefs’ fan base. There was also the matter of money. While the games served as charity fundraisers, players initially earned $25 per contest – “and we were happy to get it,” tight end Fred Arbanas said years later.

Pro football salaries at the time weren’t close to today’s seven-, eight-, and nine-figure deals. It wasn’t uncommon for players to hold down blue-collar jobs in the offseason to help pay the bills. In addition to suiting up for the Chiefs, Arbanas worked full time at a General Motors plant between seasons.

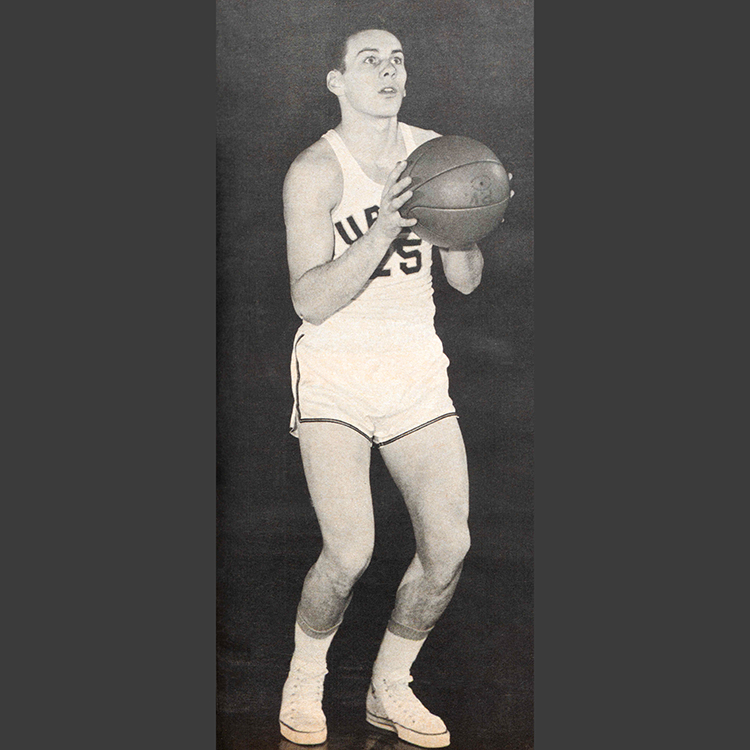

In addition to Arbanas, several players now enshrined in the Chiefs Hall of Fame played on the team in the 1960s – halfback Curtis McClintion, running back Abner Haynes, offensive lineman Ed Budde, and even quarterback Len Dawson were on the initial roster. For years, Chiefs equipment manager Bobby Yarborough ran the team.

With an average weight of 282 pounds and height of six feet seven inches, the team brought a distinct size advantage the court. They described their standard gameplan as the “real estate offense.” Several gigantic linemen would be positioned around the basket to fight for rebounds while the more agile players like quarterbacks and wide receivers took shots from the perimeter.

They commonly played teams pulled from trade associations and civic organizations, groups of teachers, high school and college teams, and basically anyone willing to meet on the court for a good cause. They even played other professional football squads.

Needing to build fan support, the Chiefs organization encourage the attention the basketball team brought. Likewise, the Green Bay Packers, Minnesota Vikings, Cleveland Browns, Chicago Bears, and other NFL franchises freely lent their names to basketball squads. Others had to get creative with their team names.

By 1975, they had played 289 games in eight states, raising some $500,000 for numerous charities.

Players also earned a little more, taking home $50 per game. The roster fluctuated over the years, with defensive lineman Buck Buchanan, linebacker Bobby Bell, wide receiver Otis Taylor, and cornerback Emmitt Thomas among the bigger names who took the court.

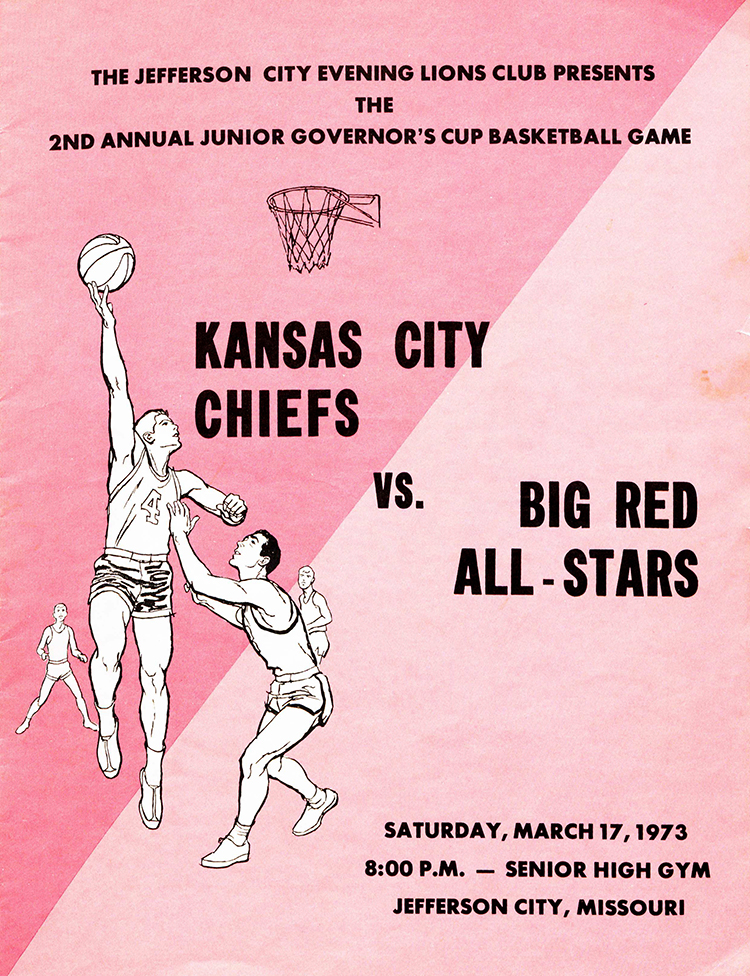

Some of the team’s most popular games came against other NFL teams. In a Super Bowl I rematch, the Chiefs took on the Green Bay Packers at the Interscholastic Field House in 1970. Kansas City’s 98-80 victory might have soothed some of the hurt from the team’s much higher-profile loss on the football field in Los Angeles a little more than three years earlier. In 1973, the Chiefs traveled to Jefferson City to take on the St. Louis Cardinals, playing as the Big Red All Stars. KC lineman Dave Hill scored 24 points in a 75-70 victory. Later that same year, the team played in Miami, handedly defeating the Dolphins 92-54.

Things didn’t always go so smoothly. In 1972, the Chiefs traveled to Denver to take on the AFC West rival Broncos, playing as Dave Costa’s All Stars. Sports Illustrated covered the game, an 80-73 loss by Kansas City despite an impressive performance by running back Warren McVea. “In one rousing spree,” the magazine wrote disparagingly, “the Broncos and the Chiefs traded the ball four times in lightning-fast action replete with unbelievable steals and dazzling interceptions – but nobody came close to scoring a basket.”

Easier matches were ahead. In 1981, the Chiefs challenged the Kansas City Council to raise money for the B.W. Sheperd State School. Mayor Richard L. Berkley, Councilman Emanual Cleaver, and others from City Hall met the Chiefs at Swinney Gymnasium on the UMKC Campus. Interestingly, area newspapers did not report the final score.

By the early 1980s, changes to the business of football meant the decline of organized offseason basketball teams.

The players’ union, the NFL Players Association, grew stronger, and salaries rose. So, too, rose the recognition of risk in engaging in organized offseason sports. Kansas City was shaken on January 26, 1979, when future Hall of Famer George Brett and other members of the Royals played a basketball game against the Chiefs in what was billed as the Challenge of the Champions.

Brett broke a bone in his thumb while diving for a loose ball. Doctors declared the injury a minor fracture and unlikely to affect his play the following season, but this did little to reassure fans eyeing the start of spring training in two short months. The Kansas City Times aired its concerns the following week. A story, headlined “Charity Games Become Big Worries for Pros,” focused not only on Brett’s break but also offseason injuries to Chiefs players in years past.

Over time, the need for players to earn offseason income by engaging in risky organized sports decreased. Still, despite the NFL’s current contract language prohibiting dangerous activities, teams have come to accept that pro athletes need to stay in shape year-round and playing other sports just doesn’t rise to the level of risky behavior.

Bob Sprenger, then the NFL’s director of public relations, might have put it best in 1979. “We can’t control their offseason activities,” he said,” … Really, what it gets down to, is that you can’t put them in a cage and let them out when spring training or training camp begins.”

Updated August 8, 2022SUBMIT A QUESTION

Do you want to ask a question for a future voting round? Kansas City Star reporters and Kansas City Public Library researchers will investigate the question and explain how we got the answer. Enter it below to get started.