A Boy-Killing Game: The 1905 Football Ban

On a cloudy and cool October in 1918, a football scrimmage was played between the Northeast and Westport high school teams on the grounds of The Parade at 15th Street and The Paseo. The Westport squad won the match handedly with a score of 19 to 0. A practice game played between two school teams on a fall afternoon might not seem like much of a big deal, but a Kansas City Star reporter took notice of what happened to be the first officially sanctioned football game played between two Kansas City schools since students were banned from playing the sport in 1905, a lapse of thirteen years.

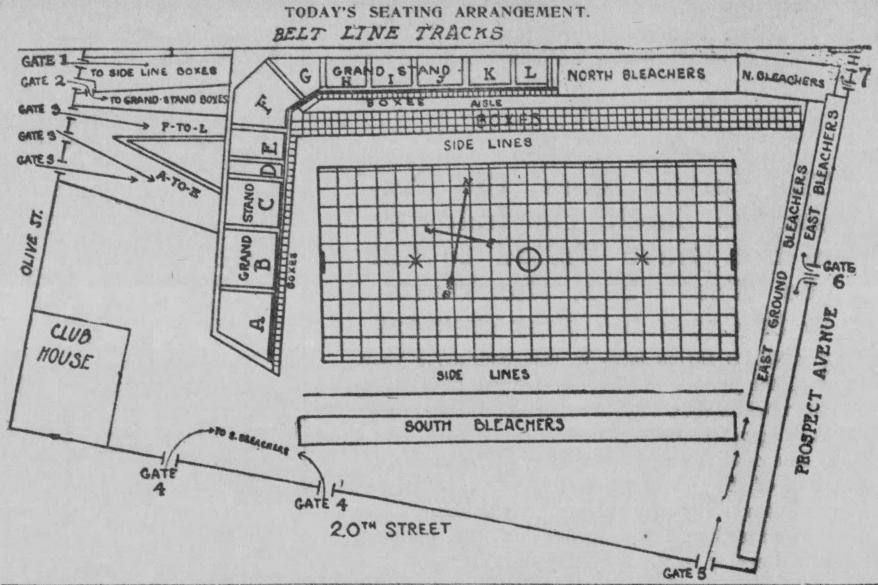

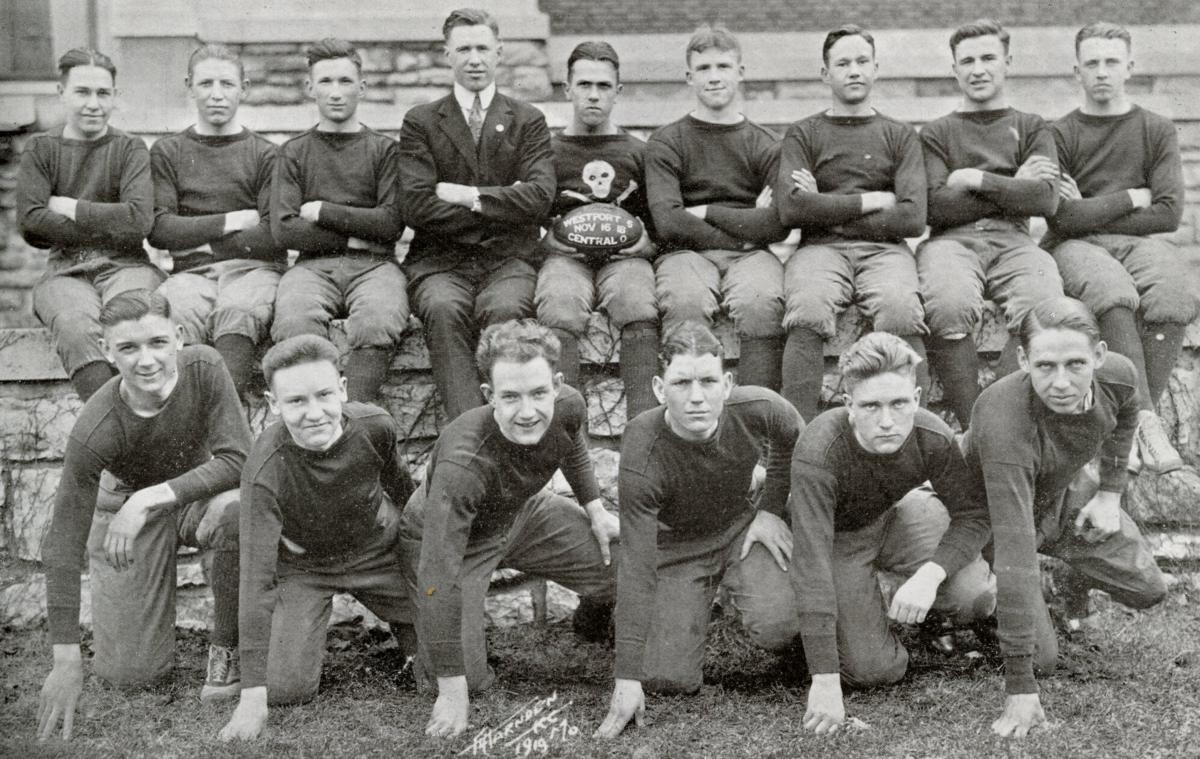

The principals and coaches of the city's four high schools: Central, Manual, Westport, and Northeast, met earlier that year and voted to permit their students to play the game. They agreed that each team would play six games, the season culminating with a city championship game. Coaches and students rushed to prepare, each organizing spring practices to prepare to hit the gridiron that fall. Sadly, the season was cut short when the health department canceled four weeks of games due to the terrible Spanish flu outbreak of that year. Nevertheless, on Saturday, November 16th, a crowd estimated at over 2,000 turned out at Association Park, now called Blues Park, at 20th Street and Prospect Avenue, to cheer on the teams.

The games played that day would have differed from those played prior to the 1905 ban, the most noticeable change being that players could now pass the ball through the air rather than simply running the ball into opposing defenses play after play after play.

Reporters at the time noted that football had been banned in the city's schools when a player for Manual suffered a fatal injury on a Thanksgiving Day game with Central back in 1905. While their account certainly contains a dramatic flair, the truth of the matter is no less interesting, albeit far less grim.

First, the game that led to the ban was not played against Central. Rather, the Manual team had traveled to Lincoln, Nebraska, to play their game against that city's high school squad. At some point in the game, Homer Gibson, the Manual's star halfback was kicked in the head. Of course, these were the days before even simple leatherhelmets afforded players a modest level of cranial protection. Gibson was unable to recover from the injury on the field and was rushed to a hospital where his condition deteriorated, first losing the ability to speak before paralysis began to take hold of the young player. Doctors determined that a concussion had caused a blood clot to develop in his brain and decided that surgical removal was the best course of action.

The surgery was a success and Gibson's condition began to improve. Ultimately, he would spend nearly a month in a Nebraska hospital before it was deemed safe for him to travel back to Kansas City. In fact, Gibson not only survived the surgery, but appears in the following year's edition of the Manual yearbook, having hung up his cleats to join the debate club.

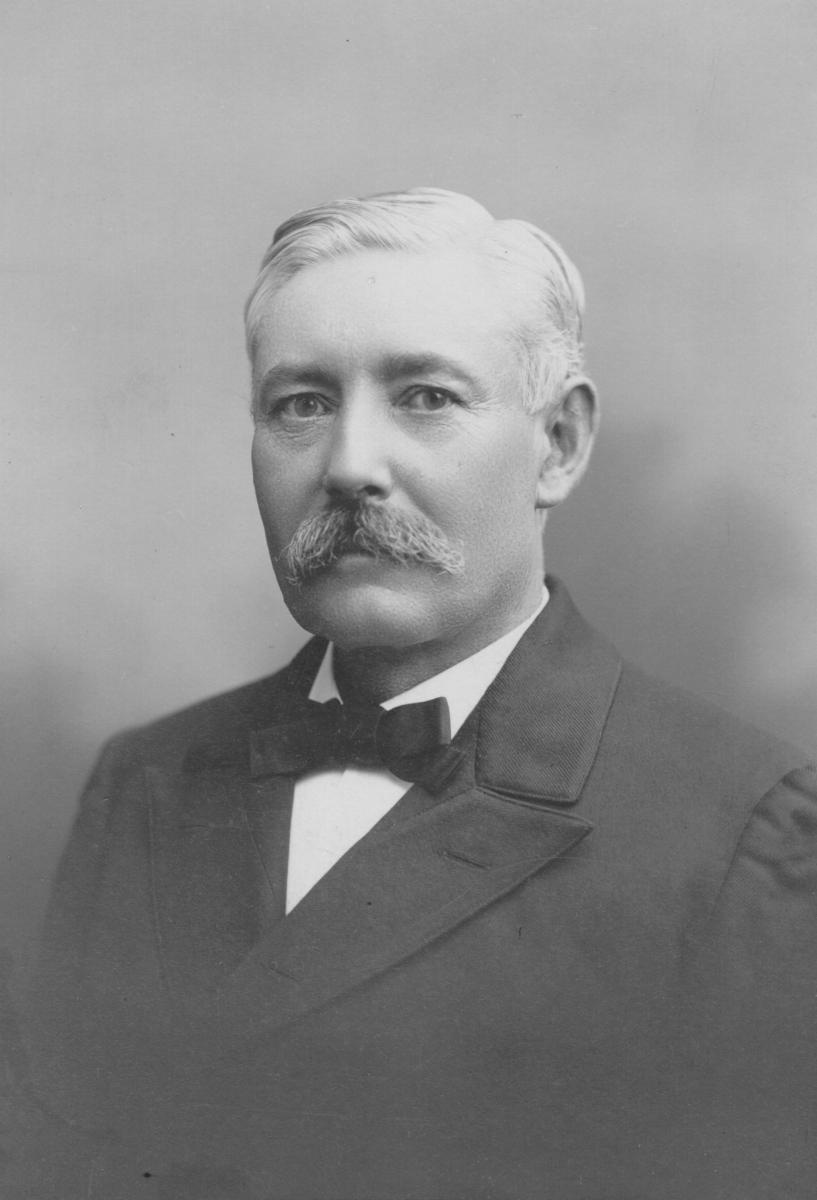

The reaction to Gibson's injury was swift and severe back home. All remaining Manual football games for the 1905 season were immediately canceled, an action initiated by members of the football team and not by school authorities. Parents across the city also began pulling their sons off of football teams. School board president Dr. James Greenwood spoke out against the game stating his belief that the sport had become more violent since he played it as a young man and expressing his support for President Theodore Roosevelt's calls to eliminate unnecessary violence from the game.

On December 16, 1905, just a few days after Homer Gibson returned from Nebraska, the principals of the Kansas City School District voted on a measure to ban the sport introduced by Dr. Greenwood. Opponents to the measure were heard, urging that the elimination of football would lead to a decline in school spirit and that students would simply continue to play the game outside of school supervision if it is banned. Despite these arguments, a vote of 38 to 8 resolved "that football, as now played, is a boy-killing, an educationally prostituting and gladiatorial sport that should not be tolerated in high and elementary schools."

The football ban in Kansas City did not happen in a historical vacuum. Rather, it came about as national outrage over a growing number of football injuries was coming to a head. Estimates differ, but 1905 is known as a particularly violent season. When considering Dr. Greenwood's proposed ban on the sport, school principals were informed that playing football had caused twenty-five deaths and over 140 serious injuries across the country by November of that year. Special attention was given to nine football deaths that occurred due to concussions of the brain or spinal cord injuries. And since football was not played at the professional level in 1905, it can safely be assumed that these statistics applied exclusively to student athletes.

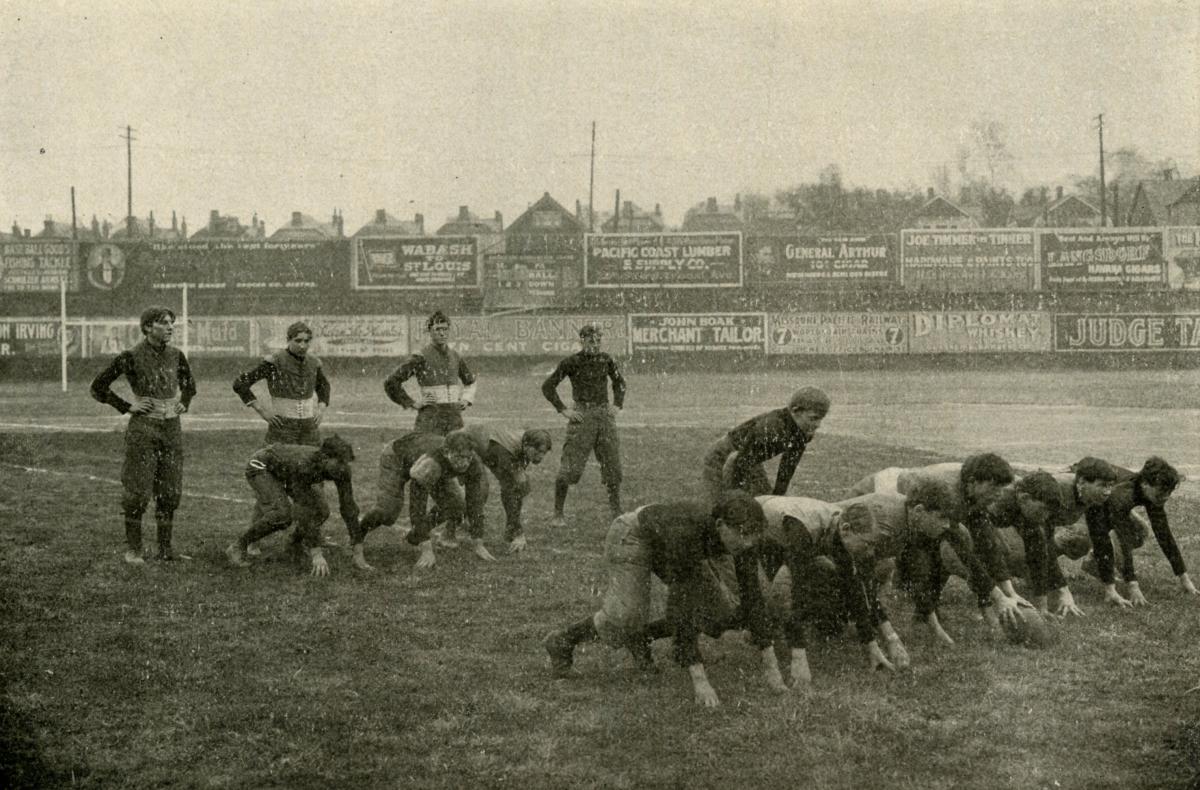

The surge in football-related injuries has been traced to the introduction of the flying wedge play by the Harvard College team in a game played against their rival Yale in 1892. The play was rather simple; as soon as the ball was snapped the offensive players would form up in a wedge shape, interlock arms, and with the ball carrier running behind them, plow their human wedge into the line of defenders. With only five yards needed to gain a first down, coaches and players quickly learned that they could successfully chip away at defenses gaining one or two yards per down using the wedge play almost exclusively. This tactic, while effective, led to 90 minute games driven by one brutal collision ending in a massive dogpile after another.

In addition to the flying wedge play, early football was noticeably different than today's game in another important way—forward passing of the ball was not permitted. Players could pass the ball laterally or to others behind them or even kick the ball away, but the ball was exclusively moved forward by running plays. Another striking characteristic of early American football was the lack of protective equipment worn by players. In fact, while early helmets were used in certain instances beginning in about the 1910s, it would not be until 1939 that they were made a piece of required equipment.

President Theodore Roosevelt lent his voice to the national outcry over the injurious 1905 football season. Unlike Dr. Greenwood, however, Roosevelt did not speak out against the game itself. He believed the sport to be firmly aligned with what he called the strenuous life, or the belief that a nation's young men benefit from a life characterized by toil, labor, and strife—all character traits, he believed, football encouraged. Roosevelt called for a meeting of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, the forerunner of today's NCAA, at the White House to discuss needed rule reforms.

New rules were subsequently adopted by the IAAUS for the following season. First, the flying wedge play was made illegal. The new forward pass would give teams the option to move the ball in a way that avoided massive pileups of players at nearly every down. To encourage passing plays, teams would additionally need to gain ten yards to achieve a first down, rendering run only gameplans obselete. Also, a neutral zone along the line of scrimmage between opposing teams was established to slow the pace of contact. Additional changes included reducing the length of the game from 90 to 60 minutes as well as the inclusion of an additional referee to help keep order.

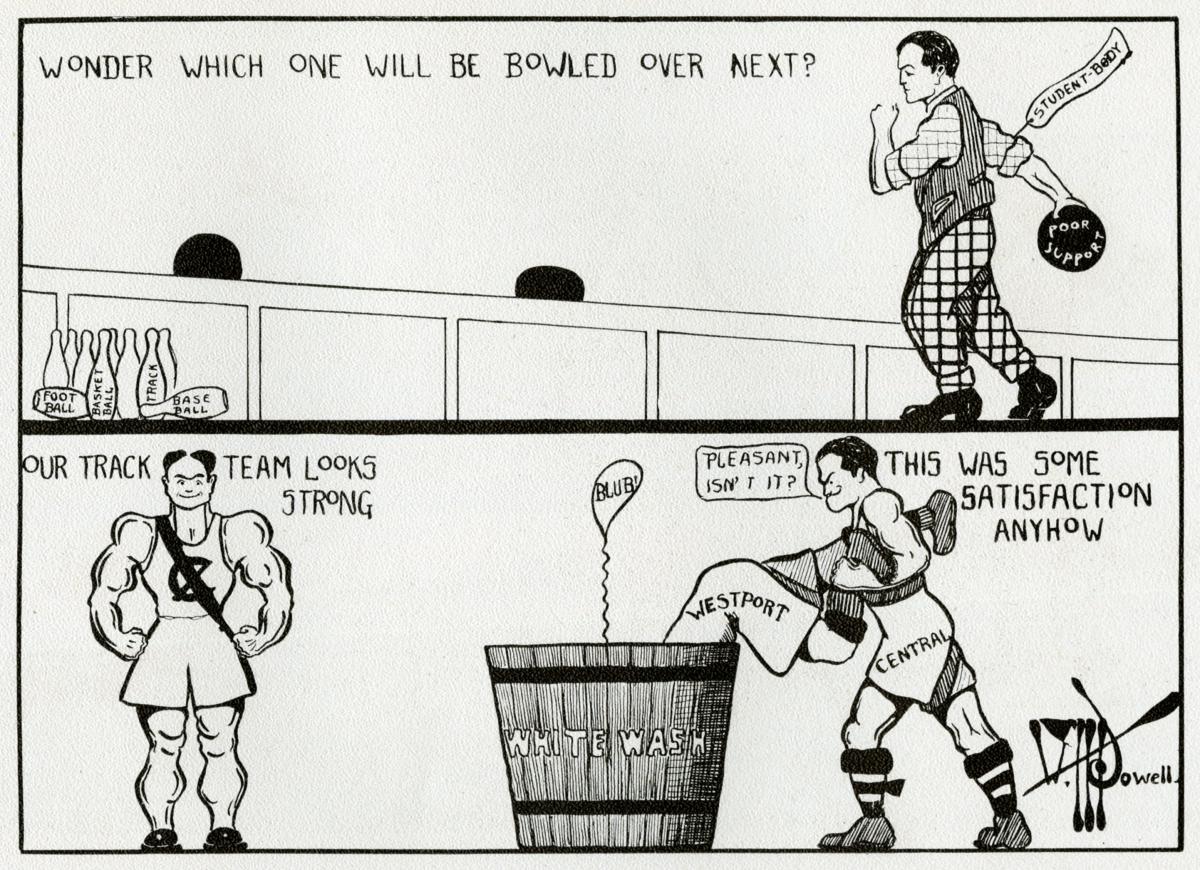

Unfortunately, the new rules would not be enacted in time to influence the Kansas City ban. No high school football was played in the city during the 1906 and 1907 seasons. While student fervor for the sport remained on the decline amongst the students at Manual, Central students led a campaign to revive the sport and managed to convince the principal there to lift the ban for the 1908 season. With Manual sitting out, Central focused upon other schools in the region who still permitted football. The revived team had a difficult task ahead of them, many of its players lacking any experience with the sport whatsoever. The squad of beginners only managed to scrape together a single victory against Leavenworth High School that year. The Central squad split the limited two game 1909 season, losing to Wentworth Military Academy, but rallying to win the Inter-City High School Championship in a game against a Kansas City, Kansas, team.

Their modest success aside, the 1908 and 1909 seasons were ultimately deemed a failure by Central students and faculty alike. The team and supporters at Central chalked its lack of success up to diminished spirit for the game amongst the student body. Administrators were happy to lay the sport to rest once again, the costs associated with fielding a football squad being much greater when compared to other sports.

The 1909 Central yearbook marked this second passing of the game with a eulogy:

That sweet, tender youth, Football, he who lingered near the veil of Obscurity so long, has at last broken his "earthy" bonds and departed. No more will his heavy-cleated cowhides clump through our echoless halls; no more will his soft, boyish, bandaged "phiz" be the object of affection among his brother "studes"—he has gone.

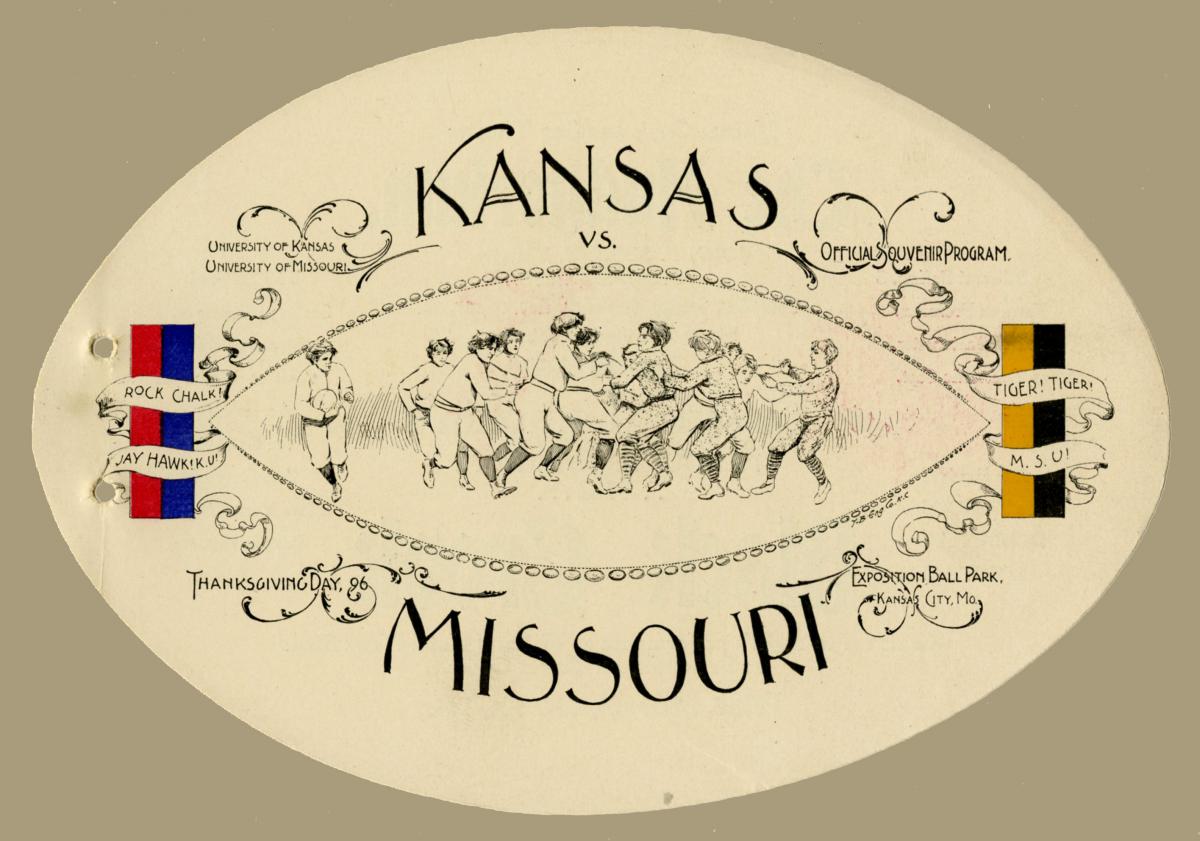

This is not to say that Kansas City's early football fanatics were simply made to go without following the 1909 season. Yearly clashes between the Missouri and Kansas university teams at Association Park were already a longstanding tradition by this time. In fact, newspaper accounts at the time described this single game as the only football action afforded to Kansas Citians in certain years.

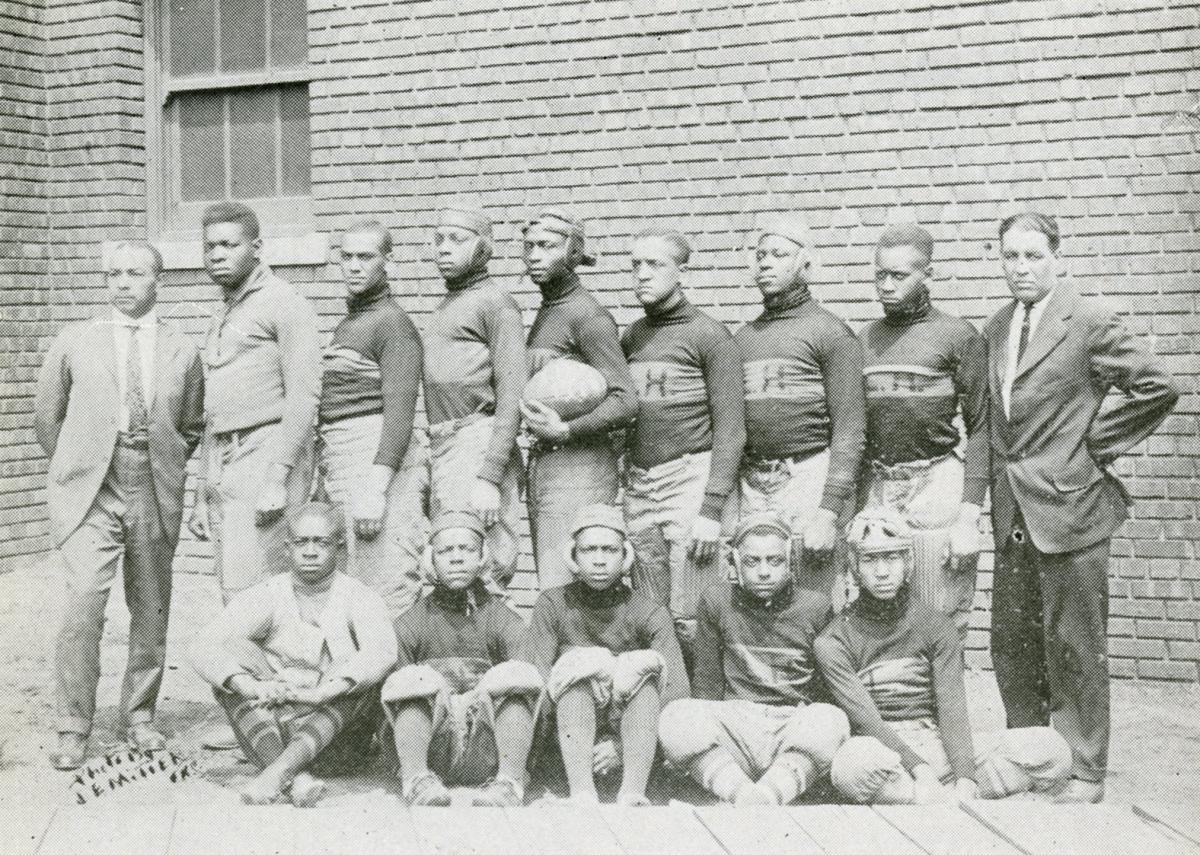

Additionally, the principals of Lincoln High, the school's African American school, permitted the game to be played by its students in the years immediately prior to the game's districtwide return in 1918, fielding squads that competed against regional high school and college teams as early as the 1914 season.

Opponents of the 1905 ban were correct in their assumption that students would find a way to play regardless of school district rules. Association teams made up of boys wishing to play under the banner of organizations like the YMCA, the Kansas City Athletic Club, and others sprang up around the city, the successful Country Club team providing the nucleus of what would become Westport's 1918 squad once the game was permitted to return.

And return it did. On a brisk November afternoon in 1918, teams representing all the Kansas City high schools: Central, the newer schools of Westport and Northeast, and even Manual, met for the first time on the gridiron since 1905. Westport, with many of its players having won championships playing together for the Country Club team, emerged as the city's first high school football champions since the ban.

Accounts of these games noted the sport's new emphasis on speed over brute force, liberal use of the forward pass, and praised the game's modified rules that helped reduce injuries. Players were even donning shoulder pads and early versions of leather helmets that, at least on the surface, provided a modicum of head protection.