Evacuation Day

On August 25, 1863, Union General Thomas E. Ewing issued Order No. 11 to forcibly remove all residents of Jackson, Bates, and Cass counties, except for those who lived within a mile of Kansas City, Westport, Independence, or one of three nearby military posts. General Ewing's critics considered the new measures to be a draconian form of martial law, but Ewing hoped that the order would end local support for the pro-Confederate guerilla forces that frequently led raids into Kansas and cut off nearby trade routes.

Earlier in the summer of 1863, General John M. Schofield, commander of the Union Army in the West, had placed Ewing in command of the newly-created District of the Border. This territory covered the counties hugging the Missouri-Kansas state line, where frequent guerilla warfare—which had its antecedents in the “Bleeding Kansas” days of the mid-to-late 1850s—undermined law and order. The biggest threat to the Union interests in the West seemed to be the pro-Confederate inhabitants of western Missouri who supported raids into staunchly Unionist Kansas. Shortly after taking command, one of Ewing's first actions was to order the arrest of hundreds of wives, girlfriends, and sisters of the suspected raiders and use them as hostages. Many of these women were held in a make-shift jail at a building in the "Metropolitan Block" on Grand Avenue, in Kansas City, Missouri.

Southern sympathizers were further outraged on August 14 when four of these captives tragically died after this building collapsed due in part to incomplete construction of the foundation and improper maintenance. Guerilla leaders William "Bloody Bill" Anderson and John McCorkle, in particular, wanted to avenge the loss of their sisters. They, and others, joined William Clarke Quantrill for his now-infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas. Over 150 of Lawrence's men and boys were killed in that raid on the morning of August 21.

In retaliation for the Lawrence Massacre, General Ewing issued Order No. 11 on August 25 in an attempt to crush Confederate resistance in western Missouri. Order No. 11 vastly exceeded his previous directives in scale and severity. Ewing required all inhabitants of Jackson, Bates, and Cass counties to leave their homes if they lived farther than one mile outside the cities of Independence, Kansas City, and Westport; or three nearby military outposts. The depopulation of these rural areas would - in theory - eliminate any armed resistance in the areas outside the control of the Union forces.

The affected inhabitants vacated their homes within a week. If they could prove their loyalty to the district commanders, they were allowed to relocate within the district. Those who could not prove their loyalty had to disperse and leave the area entirely. In their wake, the Union soldiers, many of whom were disgruntled Kansans, confiscated livestock, burned houses and other buildings to the ground, and confiscated or destroyed all grain supplies. Observers commented that the only things left on the landscape were the remnants of chimneys from the burned houses. Estimates of the number of people displaced vary widely, but the total population of the counties affected declined by roughly two-thirds. In all, the number of people who may have been forced to leave the area was likely in the tens of thousands.

For all of the disruption caused by Order No. 11, it did not accomplish its overarching goal of eliminating violence along the Kansas-Missouri border. Guerilla warfare continued until the end of the Civil War in 1865. The proponents of Order No. 11, however, argued that it must have helped prevent additional incursions into Kansas on the scale of Quantrill's Lawrence raid.

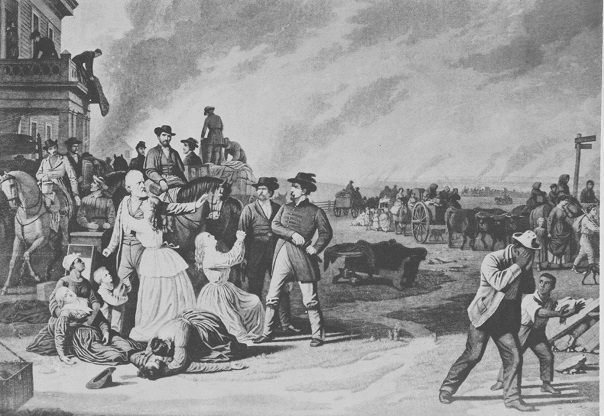

Historians continue to debate the merits and shortcomings of Ewing's orders, but in the short term it was largely considered an outrageous attack on the civilian population. As early as November, Ewing began allowing people to return to their residences if they could demonstrate their loyalty to the Union. In January, 1864, General Egbert Brown replaced Ewing and further relaxed the standards by allowing anyone who claimed to be loyal to move back. Following the war, Ewing's action on August 25, 1863, was immortalized by artist George Caleb Bingham, who strongly opposed Order No. 11 despite his pro-Unionist stance. Bingham's painting, entitled simply, Order No. 11, depicted a rural family being forcibly removed under the personal supervision of General Ewing. For several generations the painting would reinforce the views of western Missourians who despised General Thomas Ewing for his issuance of Order No. 11.

View images associated with Order No. 11 that are a part of the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Thomas E. Ewing.

- Order Number 11 Painting; reproduction of George Caleb Bingham's famous painting depicting the consequences of Order No. 11.

- Postcard of Gladstone Boulevard, at Scarritt Point; includes a picture of Judge William Hockaday Wallace's home; as a fourteen-year-old, Wallace was a victim of Order No. 11.

Check out the following books and articles about Order No. 11 held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- Thomas Ewing Jr.: Frontier Lawyer and Civil War General, by Ronald D. Smith.

- George Caleb Bingham: Missouri's Famed Painter and Forgotten Politician, by Paul C. Nagel.

- Order no. 11: A Tale of the Border, by Caroline Abbot Stanley; originally published in 1904; republished in 1969.

- "Frances Fitzhugh George - My Life," by Frances F. George; autobiographical sketch including the Civil War and Order No. 11; reprinted in the Kansas City Genealogist, Fall 2002, pp. 77-80.

- "General Orders No. 11 and Border Warfare during the Civil War," by Ann Davis Niepman, in the Missouri Historical Review, October-July 1971-1972, pp. 185-210.

- "Jackson County And Order #11," by Joanne Chiles Eakin, in The Blue & Grey Chronicle, June 1, 2004, pp. 1-5.

- "A War On Civilians: Order Number 11 and the Evacuation of Western Missouri," by Sarah Bohl, in Prologue, Spring 2004.

Continue researching Order No. 11 using archival material held by the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Vertical File: Order Number 11.

- "Order Number 11 Engraving"; framed engraving of George Caleb Bingham's painting.

- "General Orders, no. 11, 17, 151, 185"; United States, Adjutant-General's Office, 1863.

- "An Address to the Public, Vindicating a Work of Art Illustrative of the Federal Military Policy in Missouri during the Late Civil War," George Caleb Bingham, an artist whose painting depicted the atrocities of Order No. 11, speech manuscript, 1871.

- Vertical File: Residences--Bingham-Waggoner.

- "General Thomas Ewing, Jr.," by Harrison Hannahs, in the Kansas State Historical Society Collections, 1912.

- "Colonel Robert T. Van Horn: His Life and Public Service," by James M. Greenwood and Nettie Thompson Grove, in the Annals of Kansas City, 1924; describes Van Horn's assistance with Order No. 11.

- "D. A. Bryant," by J.W.L. Slavens; about a physician who was displaced by Order No. 11, in An illustrated Historical Atlas Map: Jackson County, Missouri, 1877.

- "History of Caldwell and Livingston Counties, Missouri"; describes another physician who was displaced by Order No. 11, 1886.

- "History of Howard and Cooper Counties, Missouri"; describes a farmer who was forced to move due to Order No. 11, 1883.

- "Perry Grinter"; about a farmer who was displaced as a result of Order No. 11, 1896.

- "Rural Rhymes, and Talks and Tales of Olden Times," by Martin Rice; discusses the tragedies of Order No. 11, 1893.

References:

Rick Montgomery and Shirl Kasper, Kansas City: An American Story (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 1999), 52-53.

Carrie Westlake Whitney, Kansas City, Missouri: Its History and Its People, 1808-1908, volume 1 (Chicago, IL: The S.J. Clarke Publishing, Co, 1908), 195.

A. Theodore Brown, Frontier Community: Kansas City to 1870 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1963), 181-185, 190.

Henry C. Haskell, Jr. and Richard B. Fowler, City of the Future: A Narrative History of Kansas City, 1850-1950 (Kansas City, MO: Frank Glenn Publishing, 1950), 41-42.