Bottoms Up

On April 7, 1878, Kansas City's Union Depot opened near the stockyards and meat packers in the West Bottoms. Many observers initially considered the $410,028 building (the largest west of New York) to be excessive compared to the freight and passenger traffic then passing through Kansas City, but the city's rapidly expanding railroad connections actually overwhelmed the facility in just two years.

The need for Union Depot arose after the construction of the Hannibal Bridge in 1869. The first to span the Missouri River, the bridge soon carried the traffic of eight railroads that connected Kansas City, Missouri, with the major trade centers to the east, including St. Louis, Chicago, and New York. With an ample supply of meat and agricultural products coming from the cattle trade and the city's hinterland, Kansas City became a significant hub in the nation's flow of commerce.

With all of this growth, the city lacked a large rail depot where shipments could be concentrated. The several small train stations in existence were inadequate and inefficient in handling the increased traffic. The need for a larger new depot was apparent by the mid-1870s, but budgetary constraints pushed the project back. In 1875, Kansas City nearly went bankrupt due to $400,000 in delinquent taxes. That year, a new City Charter imposed penalties on delinquent taxpayers, revitalizing the city's budget.

Several land developers, including George H. Nettleton, Wallace Pratt, C. H. Prescott, T. F. Oakes, and B. S. Henning, organized a company for the construction of Union Depot. They acquired a section of land on Union Avenue, owned by Kersey Coates, where one of the smaller depots had burned several years previously. The site was ideally situated to access the stockyards and meatpackers of the West Bottoms and enable shipment of their products eastward.

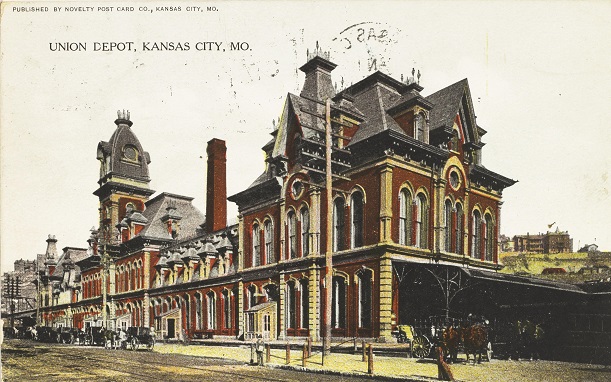

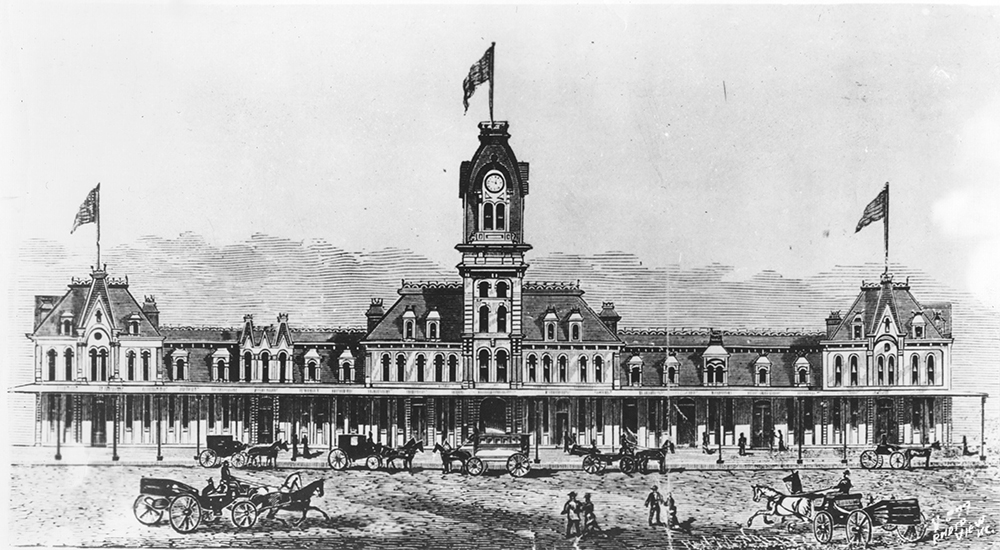

When the Union Depot opened on April 7, 1878, it seemed truly massive to the residents of a city that had a population lower than 10,000 just a decade before. The 384-foot long building displayed an intricate design, modeled after a French chateau and a blending of the Gothic and Victorian traditions. The design showcased steeples, towers, turrets, arches, cupolas, and detailed ornamentation. It was topped off by a 125-foot, four-sided clock tower. Critics of the convoluted design referred to it as a "sprawling monstrosity" or "Kansas City's Insane Asylum;" the latter a disparaging reference to the builder, who also constructed a mental hospital in Topeka, Kansas.

What the building may have lacked in subtlety, it made up for in practicality. It housed express offices, comfortable restrooms, and a restaurant; all of which were appointed with luxurious woods and metals. It was even big enough to handle Kansas City's swiftly expanding volume of rail traffic, at least for a time. A major $224,083 expansion was carried out in 1880, just two years after the building's opening. With such remodeling projects, Union Depot remained the city's major transportation hub in spite of the city's growth. By 1890 the population had more than doubled to 132,000.

The major drawbacks to Union Depot all stemmed from its location in the West Bottoms. While an excellent place to pick up packaged meat and cattle for shipment to the North and East, the West Bottoms was one of the more unseemly parts of town for passenger traffic. Coming from certain angles, passengers actually had to avoid trains on the tracks. Visitors to the city left the relative comfort of their railroad cars and were greeted with nearly four square blocks of the saloons, gambling centers, billiard halls, tattoo parlors, and brothels that surrounded the depot. The smoke of the coal-fired trains coated nearby buildings with black soot. Traveling from the depot to Quality Hill and Downtown involved a nerve-racking ride on the cable cars of the steep Ninth Street Incline.

To make matters worse, the entire West Bottoms area was prone to flooding. The 1903 flood swamped Union Depot, giving the city an impetus to construct a new and larger depot in an area free of flooding and more convenient for passengers. On October 30, 1914, the new depot, named Union Station, opened to a crowd of 100,000 people. The next day, October 31, the last train passed out of old Union Depot. The building was razed in 1915, and the bawdy area surrounding it quickly vanished.

Read a building profile of Union Depot, prepared for the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Union Depot Profile, by Asa Beebe Cross.

- Biography of Asa Beebe Cross (1826-1894), Architect, by Daniel Coleman.

Check out the following books and articles about Union Depot, held by the Kansas City Public Library:

- "Union Depot Lives on in Exhibit," by Matt Campbell, in The Kansas City Star, May 8, 2008; explains that 131-year-old doorway stone from the Union Depot is now on display at Union Station.

- "Building of Old Union Depot Sparked Business Revival after Panic of 1873," in The Kansas City Times, November 16, 1954.

- Biographical Dictionary of American Architects (Deceased), by Henry F. Withey, 1956; contains a biography of Asa Beebe Cross, designer of Union Depot, pp. 150-151.

- "He Built in the Path of Progress: Asa Beebe Cross," by George Ehrlich, in the Historic Kansas City Foundation Gazette, May-June 1983; Cross designed the Union Depot station.

Continue researching Union Depot using archival materials from the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Vertical File: Union Depot.

- Vertical File: Cross, Asa Beebe.

- Union Depot Painting, 1890; by artist George Fuller Green. Housed in Missouri Valley Room.

- Microfilm: Native Sons Scrapbooks, Roll 60 - Railroads.

- History of Kansas City, Missouri, by Theodore S. Case, 1888, Union Depot on pp. 139-160, portrait and biographical sketch of George Blossom (1827-1885), operator of the Union Depot Hotel, pp. 124, 466-468.

- "A $20,000 Blaze," in the Kansas City Evening Mail, September 22, 1875; article describes the burning of the original Union Depot.

- "A New Depot," in the Kansas City Evening Mail, September 24, 1875; discusses plans to replace the original Union Depot.

References:

Dory DeAngelo, What About Kansas City!: A Historical Handbook (Kansas City, MO: Two Lane Press, 1995), 61-62.

Carrie Westlake Whitney, Kansas City, Missouri: Its History and Its People, 1808-1908, Volume 1 (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1908), 259.

Sherry Lamb Schirmer and Richard D. McKinzie, At the River's Bend: An Illustrated History of Kansas City (Woodland Hills, CA: Windsor Publications, 1982), 42-43.

Rick Montgomery & Shirl Kasper, Kansas City: An American Story (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 1999), 97, 118, 120-121.