Exodusters Mark the Spot

On April 25, 1879, the Wyandotte Commercial Gazette reported that more than 1,000 destitute African Americans had arrived in Wyandotte City (present-day Kansas City, Kansas) in just two weeks. With a total population of just 4,612, Wyandotte struggled to meet the needs of so many former slaves who had left the South for hopes of a better life in Kansas.

Between 1879 and 1880, roughly 20,000 African Americans entered the Sunflower State. Most were former slaves who sought personal security, economic stability and a new start in life. The federal government's Reconstruction program in the South had officially ceased in 1877, and with it died many Southern blacks' hopes for equality under the law.

Following Reconstruction, the white Southerners that regained control of their state governments enacted so-called "black-codes" to disenfranchise black voters. In doing so, the South dodged the 15th Amendment to the US Constitution, which had legally guaranteed voting rights to black males. Without the protection of federal troops after 1877, Southern blacks could not exercise the full rights of citizenship. The violence and fear inflicted by the white-supremacist Ku Klux Klan illustrated in no uncertain terms that blacks remained second-class citizens in Southern society. In this environment, it did not require much of an imagination to believe that a reinstitution of slavery itself was imminent.

The vast majority of freed slaves remained in the South, but some tens of thousands sought refuge elsewhere – primarily in Kansas. Taking a cue from the biblical exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt, these black migrants came to be known as "Exodusters." Most chose Kansas as their destination for two reasons. First, due to the efforts of John Brown and other ardent abolitionists who successfully struggled to bring Kansas into the Union as a free state just prior to the start of the Civil War, Kansas enjoyed a positive reputation among blacks. Second, rumors circulated throughout the South that the federal government was providing reparations to former slaves with 40 acres of Kansas land, as well as tools and supplies.

The Exodusters found Wyandotte City, located where the Kansas and Missouri Rivers converged, to be a natural entrance point into Kansas. Most made their way to St. Louis, Missouri, then journeyed to Kansas by steamboat on the Missouri River. Once past present-day Kansas City, Missouri, the first convenient landing in Kansas was at Wyandotte. Upon arrival, the Exodusters expected a warm reception with temporary shelter and directions about how to claim their land.

As it turned out, there was really little truth to the rumors of Kansas was a dedicated refuge for newly-free African Americans. The federal government had never promised any assistance to former slaves who moved there. Additionally, racial attitudes in Kansas at this time were only marginally more advanced than was the case in the South, and the Sunflower State allowed much de-facto discrimination and segregation. Having exhausted their savings on the long journey to Wyandotte, the Exodusters subsisted on the meager rations of bread (and a very sporadic supply of meat) that the municipal administration was able to procure.

Since early April, the city's beleaguered leaders, including Mayor J. S. Stockton, had lobbied the U.S. Congress and the state legislature to provide additional relief, but these efforts did not succeed. By April 25, Mayor Stockton finally made arrangements with the Colored Refugee Relief Board, in St. Louis, to direct Exodusters to Kansas towns besides Wyandotte. State agencies at Topeka would now work with the St. Louis authorities to direct migrants more evenly across the state and provide temporary state funding for their sustenance.

In the first weeks of May 1879, most of the Exodusters at Wyandotte dispersed to other Kansas towns, including Leavenworth, Lawrence, Tonganoxie, Manhattan, and Ottawa. Wyandotte's worst struggles with accommodating the Exodusters were over. The influx of Southern blacks into Kansas continued into 1880, however, and the state faced constant difficulties in dealing with so many newcomers who lacked capital and other resources.

By the end of 1880, the Exoduster movement had finally slowed dramatically as word spread that Kansas was not the haven that rumors had indicated. Future migrants to Kansas, whether black or white, were much more likely to have saved money to invest in land and supplies before they entered the state. These realities reduced the number of Southern blacks who attempted to move to Kansas to a relative trickle, and the Exoduster movement exited the scene.

Check out the following books and articles about Exodusters in Kansas City and Kansas:

- Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction, by Nell Irvin Painter.

- Narratives of African Americans in Kansas, 1870-1992: Beyond the Exodust Movement, by Jacob U. Gordon.

- Black Frontiers: A History of African American Heroes in the Old West, by Lillian Schlissel; primarily intended for younger readers.

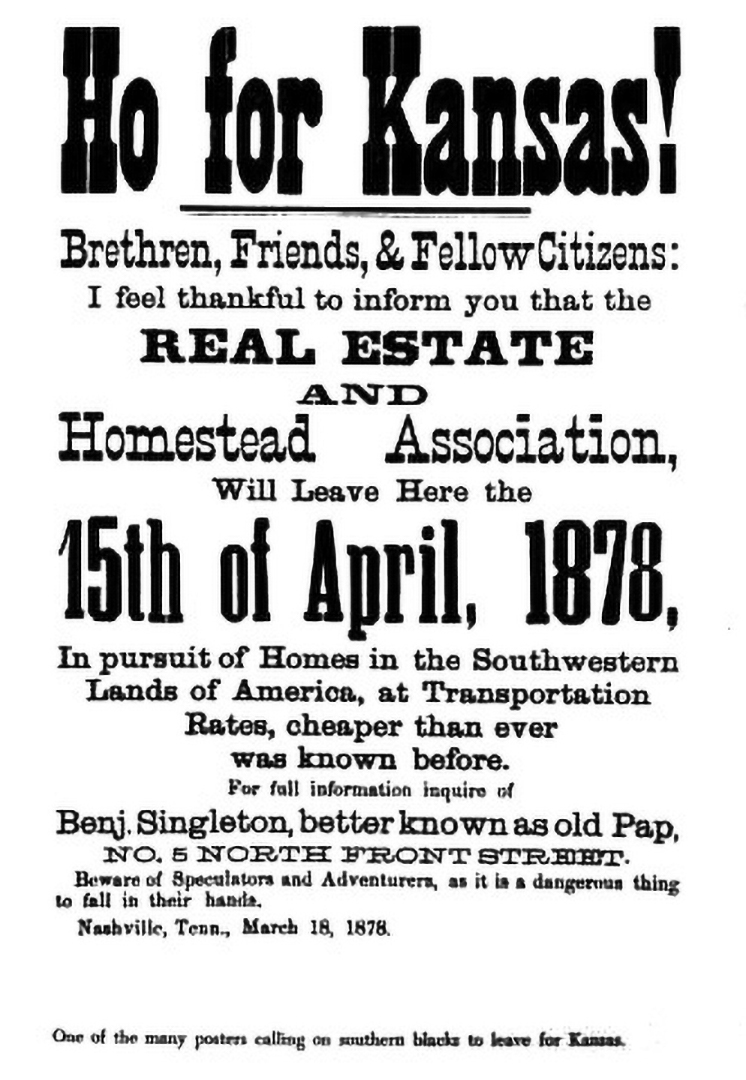

- "Benjamin, or 'Pap,' Singleton and His Followers," by Roy Garvin, in the Journal of Negro History; Pap Singleton helped organize communities of Exodusters in Wyandotte county. Also an enthusiast of the Exoduster movement, "Pap" Singleton had traveled in the South to extol the advantages of Kansas for blacks. Singleton undoubtedly had great influence in attracting many Exodusters to his home town of Wyandotte.

- "Hoeing Their Own Row: Black Agriculture and the Agrarian Ideal in Kansas, 1880-1920," by Anne P. W. Hawkins, in Kansas History.

- "But, Will This Still be 'Demus?'," by Sherda Williams, in the Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society; a historical sketch of Nicodemus, Kansas, founded by black migrants from Kentucky.

- "Aunt Clara Brown: A Black Woman Pioneer," by Barbara A. Egypt, in the Jackson County Historical Society Journal; biography of Clara Brown, an Exoduster.

- "Eliza Bradshaw: An Exoduster Grandmother," by Sam Dicks and Mattie Bradshaw, in Kansas History; contains a biography of Eliza Bradshaw originally published by her granddaughter, Mattie Bradshaw, in 1907.

Listen to The Exodusters episode (MP3) from the Kansas Memory Podcast, September 19, 2007.

Continue researching Exodusters using archival material held by the Missouri Valley Special Collections:

- Ramos Vertical File - Nicodemus, (Kan.) – History; file containing information on Nicodemus, Kansas, settled by black migrants.

References:

Rick Montgomery & Shirl Kasper, Kansas City: An American Story (Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 1999), 110.

Glen Schwendemann, "Wyandotte and the First 'Exodusters' of 1879," The Kansas Historical Quarterly 26, no. 3 (Autumn, 1960): 233-249.

Suzanna M. Grenz, "Exodusters of 1879: St. Louis and Kansas City Response," Missouri Historical Review 73, no. 1 (October, 1978), 54-70.